Galbraith once remarked that “The process by which banks create money is so simple that the mind is repelled. Where something so important is involved, a deeper mystery seems only decent” (Galbraith 1975, p. 22).

He was right on the first count. Banks operate according to the rules of double-entry bookkeeping, the key rules of which are (a) to record all financial transactions twice, once as a debit (DR) and once as a credit (CR); and (b) to ensure that the record of every transaction follows the rule that Assets minus Liabilities Equals Equity.

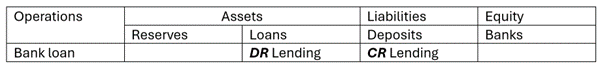

Take the statement by the Bank of England that “bank lending creates deposits” (McLeay, Radia, and Thomas 2014, p. 14). Put into a double-entry bookkeeping table, this is as shown in Table 1:

Table 1: The double-entry bookkeeping for the Bank of England's statement

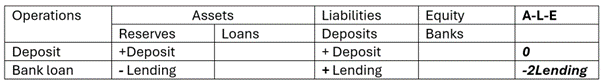

The rules about when you record something as a Debit (DR) or a Credit (CR) are quite confusing, but there’s another way to record this: use a plus key for anything that increases an account, and a minus for anything that decreases it, and make sure that the equation “Assets-Liabiities-Equity equals Zero” is obeyed. That is shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Bank lending using + and - rather than DR and CR

The equation describing this process is simply the translation of the Bank’s English into the formal language of mathematics. The verbal expression is “The rate of change of Deposits equals Lending”. In the symbols of mathematics, the “fraction” d/dt stands for “the rate of change of”, and the equals sign “=” for “equals”. This equation then is the mathematical form of the Bank of England’s declaration that “bank lending creates deposits”:

d/dt Deposits = Lending

Notice that there is no role for Reserves in that equation. That, according to mainstream economists, is the problem, because they have been teaching for decades that Reserves play an essential role in bank lending. In what they call “Fractional-Reserve Banking”, banks are supposed to take in deposits by the public, hang onto part of that as Reserves, and then lend out the rest.

This is how the popular textbook by Mankiw puts it:

Eventually, the bankers at First National Bank may start to reconsider their policy of 100-percent-reserve banking. Leaving all that money idle in their vaults seems unnecessary. Why not lend some of it out and earn a profit by charging interest on the loans?... if the flow of new deposits is roughly the same as the flow of withdrawals, First National needs to keep only a fraction of its deposits in reserve. Thus, First National adopts a system called fractional-reserve banking. (Mankiw 2016, p. 332)

Trying to put “fractional reserve banking” into double-entry bookkeeping terms causes immediate problems. If you try to show the loan increasing Deposits, then you violate the rules of accounting: the row does not sum to zero, as it should.

Table 3: The obvious accounting error in the Fractional Reserve Lending model

The line also shows the borrower getting the money—the Deposit account increases—but there’s no debt recorded by the bank against the borrower’s account. There must be a missing step here.

And there is, but you won’t see this explained in any mainstream economics textbook, because they don’t really care about money: the whole point of mainstream models of money is to justify not including banks, and debt, and money in macroeconomic models. Once they have that excuse—even if it’s a bad one—then they can persist with their preferred model of capitalism as a barter system, in which money plays no essential role.

It also suits their anti-government ideology. There are two control mechanisms in the model of “Fractional Reserve Banking”, both of which are under the control of the government: the creation of Reserves, and the fraction that banks are required to hang onto of any deposit. If there’s too much money—and therefore inflation—it’s the government’s fault; if there’s too little money—and therefore deflation—it’s the government’s fault. The private banking sector gets off scot-free.

That is the real reason that they’re trying to hide this simple “bank lending creates deposits” equation, whether they’re aware of it or not. If you take this equation seriously, then you have to include banks, and debt, and money, in macroeconomic models. Neoclassicals leave all three of them out, and yet purport to be modelling capitalism.

The missing steps in “Fractional Reserve Banking”

If they took money seriously, they’d notice the flaw in Table 3 and realise that two amendments were necessary: firstly, to make the line obey the Laws of Accounting, falling Reserves can be paired with rising Loans. Secondly, for the borrower to actually get any money, the loan must be in cash (or some other negotiable instrument): the borrower has to receive cash in return for accepting the liability of the loan from the Bank.

Table 4: The Banking Sector's view of Fractional Reserve Banking done properly

Table 5: The private non-banking sector's view of Fractional Reserve Banking done properly

So at least two tables are needed to show the process fully (Table 4 and Table 5), whereas one was enough for the real-world process shown in Table 1. Then the model works, and the equation gives Reserves a necessary role in lending.

There’s just one problem: when was the last time you (or anyone else) got a loan in cash? That’s the province of loan sharks these days, not banks, who directly credit the account of the borrower when they make a loan—or they credit the account of a merchant when you swipe your credit card to buy something at a shop.

What they’re leaving out

By omitting banks, private debt and money from macroeconomics, Neoclassical economists are leaving out of their analysis the main factors that cause booms and busts in a capitalist economy.

You might think that describing capitalism’s cycles accurately might be of some importance to Neoclassical economists. And it is, but only so long as the explanation fits within their paradigm. Part of that paradigm is that money doesn’t have what they call “real” effects—by which they mean cause changes in factors like GDP and employment. So they ignore data like that shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, which are copied from my post “Why Credit Money Matters” (posted here on Patreon and here on Substack). Ultimately, they’ll ignore the Great Recession/Global Financial Crisis, the same way they ignored the Great Depression.

If you like my work, please enable me to continue doing it by supporting me for as little as $1 a month (or $10 a year) on Patreon, or $5 a month on Substack.

Figure 1: Private debt, credit and unemployment in the USA

Figure 2: Correlation between credit and unemployment 1990-2014

Galbraith, John Kenneth. 1975. Money: whence it came, where it went (Houghton Mifflin: Boston).

Mankiw, N. Gregory. 2016. Principles of Macroeconomics, 9th edition (Macmillan: New York).

McLeay, Michael, Amar Radia, and Ryland Thomas. 2014. 'Money creation in the modern economy', Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, 2014 Q1: 14-27.

Indeed accounting is a powerful temporal universe reality anchoring discipline especially when it is wielded by banks to enforce their monopoly paradigm of Debt Only as in the burden to repay in the creation and distribution of new money.

But what if utilizing the accounting equation we credited 50% of the price of virtually everything to the consumer at retail sale, and the government rebated that credit back to the merchant granting it to the consumer? That would macro-economically implement beneficial price and asset DEFLATION which is a destruction of the profit-making orthodoxy that deflation is bad for commercial agents, and enlightens the fact that retail sale is the sole aggregative as in universally participated in/personally economically effecting point in the entire economic process (worthy of a non-Noble prize in economics if I do say so myself) and is thus the perfect place to implement the above monetary policy because:

1) it mathematically doubles everyone's purchasing power and so

2) potentially the demand for every enterprise's goods and services,

3) ends inflation forever and last but not least

4) transforms the often onerous experience of going to the store to buy something into the greatest opportunity to self actualize gratitude for a gift since meditation and prayer. Exactly what an increasingly hostile and chaotic world needs.