An essential component of Neoclassical microeconomics is the proposition that firms maximize their profits by equating marginal revenue—the addition to total revenue caused by the last unit sold—to marginal cost—the addition to total costs caused by the last unit produced. This proposition plays a fundamental role in all DSGE-based macroeconomic models too, in the form of profit maximization rules for the competitive and monopolistic industry sectors that are integral parts of these models. The former maximize profits by setting price equal to marginal cost: since they lack market power, for them, the market price is a constant, and therefore price equals marginal revenue. The latter set price at a markup above marginal cost, at the point where marginal cost equals marginal revenue.

This is Chapter 5 from my forthcoming book Rebuilding Economics from the Top Down, which will be published by the Budapest Centre for Long-Term Sustainability and the Pallas Athéné Domus Meriti Foundation. I am serialising the book chapters here. A watermarked PDF of the manuscript is available to supporters.

The formulas in DSGE models that apply these rules are normally far more complicated than the simple rules taught in microeconomic textbooks, but they are based on the same principles: setting marginal revenue equal to marginal cost maximizes profits, because these are the slopes respectively of total revenue and total cost. When the slopes of the total revenue and total cost curves are the same, the gap between them—which is total profit—is maximized.

There are logical problems with this argument (Keen and Standish 2010, 2015; Keen 2004, 2005), but there is a far more important problem: the conclusion that a firm maximises profits by equating marginal revenue and marginal cost requires that marginal cost rises with output.

The logical basis of that condition is the "The Law of Diminishing Returns", that output rises as variable inputs rise, but at a decreasing pace. To cite Samuelson and Nordhaus's textbook again:

Under the law of diminishing returns, a firm will get less and less extra output when it adds additional units of an input while holding other inputs fixed. In other words, the marginal product of each unit of input will decline as the amount of that input increases, holding all other inputs constant. (Samuelson and Nordhaus 2010b, pp. 108-109)

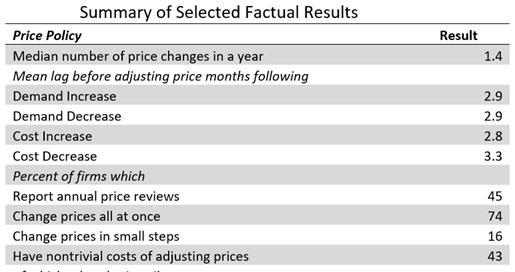

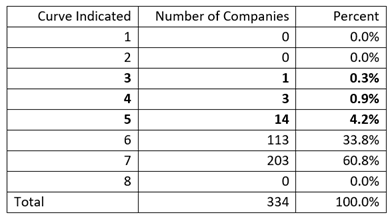

The Law of Diminishing Returns generates the standard model of a firm's cost structure, in which marginal costs are steeply rising, the average total cost curve is U-shaped, and average fixed costs are relatively small—see Figure 4, which uses the numbers from the toy model in Samuelson and Nordhaus's textbook (Samuelson and Nordhaus 2010b, pp. 127-131).

Figure 4: The standard textbook model, with a U-shaped average cost curve because of diminishing marginal productivity

The Law of Diminishing Returns is logically correct, given its assumptions, as is the shape of the cost curves derived from it. But it is also, to quote the humourist H. L. Mencken, "neat, plausible, and wrong". When economists have investigated the actual cost structures of real firms—as opposed to the imaginary ones with which economics textbooks abound—the universal finding has been that, for the vast majority of firms, marginal cost is either constant, or falls with increasing output.

The last economist to discover this was Alan Blinder, who ranks almost as highly as Blanchard in the pantheon of Neoclassical economics: he was Vice-Chair of the Federal Reserve, Vice-President of the American Economic Association, and was and remains a prominent "New Keynesian" macroeconomist.

A distinguishing feature of "New Keynesian" DSGE models, compared to "New Classical" RBC ("Real Business Cycle") models, is that New Classicals assume that prices adjust instantly to clear markets, whereas New Keynesians assume that prices are "sticky"—and hence that some unemployment of resources is involuntary. New Keynesians came up with many theories as to why prices should be sticky, each with different implications for the economy. To resolve this debate, Blinder decided to do a survey of American manufacturing firms, to see if their prices were indeed "sticky", and if so, why.

The survey itself was enormous: principal staff—Presidents, CEOs, Vice-Presidents, senior managers, and the like (Blinder 1998, Table 3.5, p. 73)—of 200 firms were interviewed face-to-face by Blinder and his thirteen graduate student assistants (Blinder 1998, p. xiii). The output of those firms accounted for "7.6 percent of the total value added in the nonfarm, for-profit, unregulated sector" of the US economy (Blinder 1998, p. 67). It was, without a doubt, the most representative survey ever undertaken of the cost structures and behaviours of corporations.32F

It also contained a surprise for Neoclassical economists, which Blinder introduced as follows:

Another very common assumption of economic theory is that marginal cost is rising. This notion is enshrined in every textbook and employed in most economic models. It is the foundation of the upward-sloping supply curve…

The overwhelmingly bad news here (for economic theory) is that, apparently, only 11 percent of GDP is produced under conditions of rising marginal cost.33F Almost half is produced under constant MC … But that leaves a stunning 40 percent of GDP in firms that report declining MC functions. (Blinder 1998, pp. 101-102. Emphasis added)

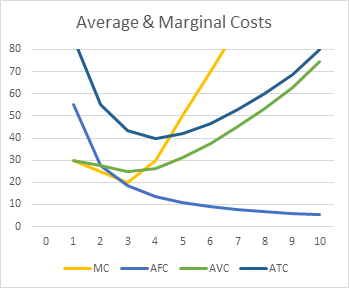

Blinder summarised this result in what is possibly the ugliest drawing ever published in an economics book (Blinder 1998, Figure 4.1, p. 103). Table 1 reproduces the data in that Figure.

Table 1: Marginal cost structures reported by Blinder's sample of 200 firms (Blinder 1998, p. )

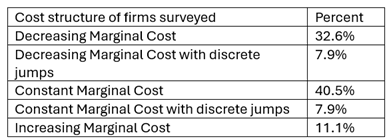

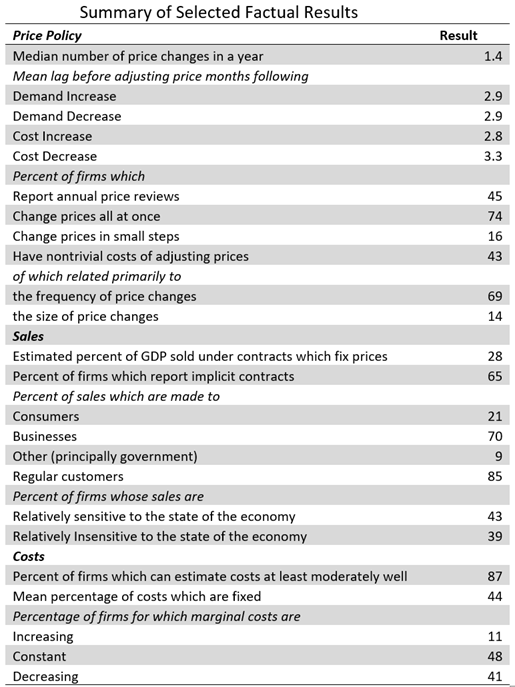

In fact, virtually all of Blinder's empirical findings were a surprise to Neoclassical economists. For my purposes here, the second-most important surprise was that average fixed costs were extremely high—compared to conventional economic theory—at on average 44% of average total costs at the firm's normal operating level (see Table 2). Compare that to Samuelson and Nordhaus's toy model rendered in Figure 4, where average fixed costs are far smaller than average variable and marginal costs.4

Table 2: Blinder's summary of his empirical results (Blinder 1998, p. 106)

Blinder concluded that:

While there are reasons to wonder whether respondents interpreted these questions about costs correctly, their answers paint an image of the cost structure of the typical firm that is very different from the one immortalized in textbooks. (Blinder 1998, p. 105. Emphasis added)

Though these results were a surprise to textbook writers, they should not be a surprise to anyone who had ever worked in a manufacturing firm—or surveyed them about their cost structures. The definitive survey of such surveys was done by Fred Lee (Lee 1998). He found 71 surveys between 1924 and 1979, all of which found the same result, that marginal costs are constant or falling for the vast majority of firms.

The definitive explanation for this phenomenon—which contradicts the "Law" of Diminishing Returns—was given by Andrews in 1949:

On the usual assumptions, the static law of diminishing returns is held to justify the short-run average-cost curve being drawn as U-shaped. The rising branch of the U, in particular, is justified by the assumption that there will be an optimum dosage of the direct ["variable costs"] cost factors, after which average direct costs rise and, in the end, more than counterbalance the effect of the falling overhead-cost curve ["fixed costs"].

However, the rising part of the average direct-cost curve, and hence of the average total-cost curve, even when it would exist, is not relevant to normal analysis. The normal situation is that the businessman will plan to have reserve capacity, his average-cost curve falling for any outputs that he is likely to meet in practice, and his average direct costs, which the second part of this paper will treat as of crucial importance in the theory of pricing, normally being practically constant for very wide ranges of output. (Andrews, Lee, and Earl 1993, p. 78; Andrews 1949)

The reasons why real-world firms have substantial excess capacity, and therefore do not experience diminishing marginal productivity, are quite simple.

Firstly, Neoclassical textbooks describe the "typical" factory as a cartoonish shamble. For example, this is Mankiw's explanation of why "Hungry Helen's Cookie Factory" experiences diminishing marginal productivity:

At first, when only a few workers are hired, they have easy access to Helen's kitchen equipment. As the number of workers increases, additional workers have to share equipment and work in more crowded conditions. Hence, as more and more workers are hired, each additional worker contributes less to the production of cookies…

when Helen's kitchen gets crowded, each additional worker adds less to the production of cookies; this property of diminishing marginal product is reflected in the flattening of the production function as the number of workers rises… Because her kitchen is already crowded, producing an additional cookie is quite costly. Thus, as the quantity produced rises, the total-cost curve becomes steeper. (Mankiw 2001, pp. 273, 275)

"Hungry Helen's Cookie Factory" is, of course, a fantasy: there is no such firm. Nor do "Thirsty Thelma's Lemonade Stand" or "Big Bob's Bagel Bin" exist: they are all simply products of Mankiw's febrile (and alliterative) Neoclassical imagination. Equally, "Al's Building Contractors" is a fictional example that Blinder uses in his textbook (Baumol and Blinder 2011).35

In the real world, factories are designed by engineers to reach peak performance at or very near capacity. As Eiteman put it in 1947, engineers design factories:

so as to cause the variable factor to be used most efficiently when the plant is operated close to capacity. Under such conditions an average variable cost curve declines steadily until the point of capacity output is reached. A marginal curve derived from such an average cost curve lies below the average curve at all scales of operation short of peak production, a fact that makes it physically impossible for an enterprise to determine a scale of operations by equating marginal cost and marginal revenues unless demand is extremely inelastic. (Eiteman 1947, p. 913)

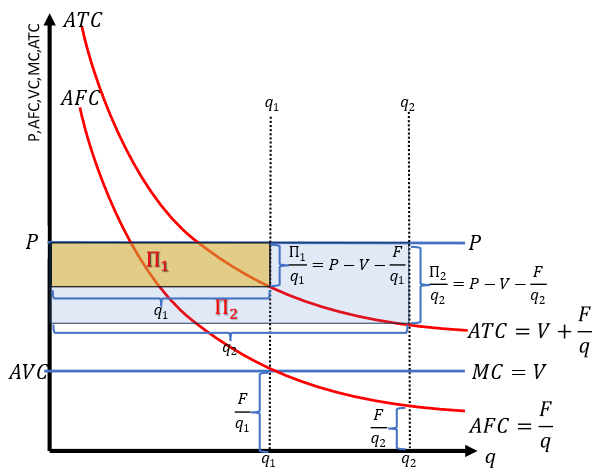

Real-world manufacturers, when they had the Neoclassical model explained to them, have often felt insulted by it. For example, Eiteman and Guthrie sent a survey to one thousand firms, which asked them to nominate which of 8 curves most closely approximated their average costs (Eiteman and Guthrie 1952, pp. 834-835). Of the 366 firms who replied, literally only one selected Curve 3, which was the one that is most like the standard drawing in Neoclassical textbooks (such as that from (Samuelson and Nordhaus 2010b, p. 131))—see Table 3, where the drawings that were strongly (No. 3) to weakly (No. 5) similar to the textbook drawing are highlighted in bold. On the other hand, over 60% of firms chose Curve 7, which had costs declining right out to capacity output, and another 34% chose the very similar Curve 6, which showed a slight rise in costs as output approached capacity.

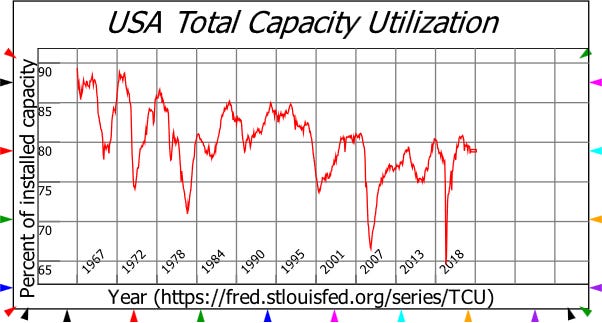

Table 3: The responses to Eiteman and Guthrie's survey on the shape of the average cost curve: "Table II. Choice of Cost Curve by Companies Without Reference to Number of Products" (Eiteman and Guthrie 1952, p. 837)

Eiteman and Guthrie noted that "The replies demonstrate a clear preference of businessmen for curves which do not offer great support to the argument of marginal theorists," and continued that "If some of the personal comments of those who answered the questionnaires were to be repeated here, they would serve further to emphasize this conclusion". They cited one businessman, who remarked that:

"'The amazing thing is that any sane economist could consider No. 3, No. 4 and No. 5 curves as representing business thinking. It looks as if some economists, assuming as a premise that business is not progressive, are trying to prove the premise by suggesting curves like Nos. 3, 4, and 5." (Eiteman and Guthrie 1952, p. 838. Emphasis added)

Secondly, when a factory is first constructed, it is built with expansion of sales in mind: a factory which operates at 100% capacity on day one of its operations is a factory that was too small in the first place.

Thirdly, in a genuinely competitive industry, virtually every firm hopes to increase its market share—and precisely because this will increase its profits. It needs spare capacity in order to do this, and since all firms do it, the aggregate potential output of the industry substantially exceeds the proportion that is actually used. Even during the boom years of the 1960s, capacity utilization in the American economy never exceeded 90%, and it has trended down ever since—see Figure 5.

Figure 5: Aggregate capacity utilization in the USA: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TCU#

The preconditions needed for diminishing marginal productivity to apply therefore do not exist in the real world. They exist only in the childish imaginations of Neoclassical textbook writers.

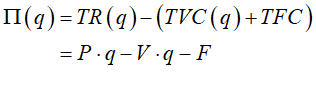

In 1949, Andrews sketched the standard real-world situation, in which diminishing marginal productivity does not apply, because a well-managed firm has idle capacity (Andrews, Lee, and Earl 1993, p. 80). This standard cost structure is reproduced in Figure 6. The practical import of this realistic representative shape of the cost curves for a manufacturing firm was given by Eiteman in 1948:

marginal cost curves will lie below average cost curves at all points of operation short of capacity. As a consequence, marginal cost curves will no longer intersect marginal revenue curves (1) when average revenue curves are horizontal or (2) when average revenue curves are high and almost horizontal. Under either of these conditions, business managers would simply produce as much goods as the current market would absorb without reference to marginal cost and marginal revenue. (Eiteman 1948, P. 900. Emphasis added)

The impact of this on both Neoclassical micro and macroeconomics is devastating.

Neoclassical microeconomics is predicated on the output level of the firm being based on its marginal cost. A profit-maximizing firm produces where marginal cost equals marginal revenue, because that output level maximizes profits: any higher output level than that actually reduces profits. But as Figure 6. illustrates, marginal cost (which equals variable cost when it is a constant with respect to output) lies well below total cost: any firm that did price at marginal cost would rapidly go bankrupt. The real-world profit-maximization condition is to sell as many units as possible—and preferably at the expense of sales to your rivals, with whom you compete, not on price, but on non-price issues like product differentiation. Hence, Figure 6 shows price P as a constant, not because of a silly Neoclassical assumption like "perfect information", but because in a mature industry in the real world, additional sales by one competitor normally come at the expense of the sales by another.

Additional output lowers average fixed costs, which are a very significant component of total costs. Lower per unit fixed costs, with constant per unit variable costs and—in a competitive industry where non-price, product-differentiation-based competition dominates—this results in rising total and per-unit profits as capacity utilization rises, right out to the factory's capacity.

Figure 6: Profit, Revenue and Costs at the target output level for the representative firm

Real-world profit maximization, therefore, involves selling as many units as possible, rather than stopping selling when "marginal cost exceeds marginal revenue". Any real-world sales manager who told his staff to stop selling would (and should) be sacked.

This is why Blinder described the results of his survey as "overwhelmingly bad news … (for economic theory)". Not only does the theory not describe the behaviour of real-world firms, but all the welfare conclusions that flow from marginal this equalling marginal that disappear as well—and they have already been destroyed in any case, by the logical fallacies in the derivation of the market demand curve covered in the previous chapter.

Macroeconomics that is based on Neoclassical microeconomics inherits these false microeconomic assumptions, and they play critical roles in the algebraic derivation of an RBC or DSGE model. But in the real world, which these models purport to describe, these conditions are strongly violated.

Therefore, even if it were possible to derive macroeconomics from microeconomics—which the previous chapter showed was a fool's errand for any complex system—then Neoclassical microeconomics is not the right foundation for it.

So, what to do? I'll give my alternative in the following chapters, after I briefly lay out the mathematics of real-world profit maximization, and speculate about what a real-world microeconomics might look like.

Appendix: Real World Profit Maximization and Real World Microeconomics

Eiteman's conjecture—that the profit-maximisation strategy of real-world firms is to sell as many units as possible—is easily illustrated using Figure 6. A firm with the cost structure of a typical real-world firm has average fixed costs of AFC=F (which are a substantial component of total costs at the target output level—of the order of 40% of the market price, according to Blinder's research), constant variable costs per unit AVC=V—so that marginal costs are also constant, and equal to V—total revenue which is equal to the market price P times the quantity sold, and a price level P that substantially exceeds average variable and hence marginal costs: P>V.

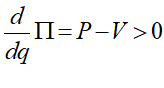

The profits of the firm are given by Equation :

The differential of profit with respect to the quantity sold is therefore always positive:

Therefore, as Eiteman said, the best strategy for the firm is to sell as many units as it can. Since its competitors are all trying to do the same thing, while market demand is, for mature industries, a relatively stable fraction of GDP, this leads to the evolutionary competitive struggle we witness in most real-world markets.

We can build a more informative analysis of actual profit maximizing behaviour by considering, not total profit, but profit per unit:

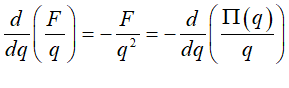

The differential of profit per unit with respect to q is:

This is obviously identical to the negative of the differential of fixed cost per unit:

In words, Equation says that the increase in profit per unit is identical to the fall in fixed cost per unit. This is the essence of the real-world profit maximization strategy: to reduce fixed cost per unit by increasing sales. Profit per unit then rises precisely as much as fixed cost per unit falls. This changes the focus of attention from the Neoclassical obsession with marginal costs—which manufacturers have revealed in numerous surveys is of little importance to actual production decisions, since it is normally either constant or falling and well below price (and "marginal revenue")—to average fixed costs, and both setting a price and achieving a sales target which substantially exceeds the breakeven point (where total costs equal price).

This confirms the graphical intuition in Figure 6. An increase in output means that the height of the rectangle for total fixed costs falls, while the height of the rectangle for total variable costs remains constant, as does the height of the rectangle for total revenue. The falling height of average fixed costs means that the gap between average revenue and average costs grows. Total profit therefore rises with rising output, because the substantial fixed costs of production are spread over a larger number of units sold. Profit per unit grows precisely as fixed cost per unit shrinks.

Given these fundamental problems with both the theory of demand and the model of production, the only thing one can say in favour of Neoclassical microeconomics is that it gives Neoclassical microeconomists something to do. But their work is worse than useless in the real world: with of the order of 95% of firms not having the pre-conditions to experience diminishing marginal productivity, and a theory of demand that does not transcend a single individual, the games Neoclassical microeconomists play are just that: games.

This real-world analysis raises the possibility of an evolutionary microeconomics that, while it could not be used to derive macroeconomics, would be compatible with the macroeconomics I will develop in subsequent chapters, and could also say something useful about actual competitive behaviour. An increase in sales by one firm will give it more internally generated funds to invest and both expand output and differentiate its product further, while the allure of large profits would encourage innovation by small, less profitable firms aspiring to become big profitable ones.

This dynamic, evolutionary process could explain the actual distribution of firm sizes, which as Axtell established, do not conform to the Neoclassical taxonomic classes of "monopoly, oligopoly, and competitive" but instead display a power-law "Zipf" distribution (Axtell 2001, 2006). As Axtell remarked, "The Zipf distribution is an unambiguous target that any empirically accurate theory of the firm must hit" (Axtell 2001, p. 1820). The Neoclassical model has no chance of doing so, while an evolutionary model in which size enables faster growth, and the profitability of large companies' finances increasing scale by them, while their success encourages product innovation by their smaller rivals, just might be able to reproduce the actual structure of real-world markets.

Two unpublished working papers by Ormerod, Roswell and Smith at Volterra Consulting provide examples of the type of evolutionary modelling which could replace sterile and irrelevant equilibrium microeconomics that Marshall gave birth to, with what Axel Leijonhufvud aptly christened "The Totem of the Micro": the drawing of intersecting market supply and demand curves (Leijonhufvud 1973, p. 331). "The Evolution of Market Structure and Competition" and "An Agent-Based Model of the Evolution of Market Structure and Competition" model a market with a single supplier that is then opened to competition, in which entrants diversify their rival products on the basis of both price and quality. The resulting market structure approximates the Zipf distribution of firm sizes which Axtell identified in the empirical literature, and justifiably declared that "The Zipf distribution is an unambiguous target that any empirically accurate theory of the firm must hit" (Axtell 2001, p. 1820). The evolutionary dynamics of competition and innovation, which Marshall saw as "The Mecca of the economist" (Marshall 1898, p. 43), was not possible in his day, but it is in ours. It should be the future of microeconomics.

From here on, my focus changes to how economics should be done, rather than the travesties in how Neoclassical economists have done it in the past—though I return to Neoclassical travesties on energy and climate change in Chapters 13-15.

Here's the beginning of the end of the idiocies of neo-classical macro and of the fallacy of Dynamic Stochastic General Equillibrium: A 50% Discount/Rebate policy at retail sale and a 50% Dual Gift to the banks and to the individual at point of loan signing and the other policies of the new monetary paradigm. The 50% Discount/Rebate at retail sale doubles individual demand while simultaneously implementing beneficial price and asset deflation which integrates the self interests of individual and commercial agents. The 50% Dual Gift at loan signing implements continuous debt jubilee into the economy thus ending the dominating monopolistic paradigm of finance and the inevitable build up of private debt. It transforms DSGE into DSGMD, Dynamic Stochastic General Monetary Disequillibrium.

The destruction of anomalous orthodoxies and the beneficial inversion of temporal universe realities: classic signatures of historical paradigm changes. All objections are just "truths" within the present paradigm. Align further regulations with the new paradigm concept to solidify and stabilize it because mankind has shown itself to not be an entirely rational or ethical species and "learn by doing". Nuf said.

A critical element in the law of diminishing returns is the evolution of continuous improvement tools and the Toyota Production System. In this environment we learn to invest successfully at small regardless of scale. Continuous improvement done correctly, destroys the Pareto Principle. We can attain more output from the same fixed cost. From J.M. Clark Overhead Costs in Modern Industry --- "Knowledge is the only instrument of production that is not subject to diminishing returns."