When the Experts are Wrong

How can the public cope if the so-called experts get money wrong?

YouTube popped a video into my feed of Niall Ferguson (the author of The Ascent of Money: a financial history of the world) being interviewed on the TRIGGERnometry show. He was asked the inevitable question about governments “living beyond their means”, and gave the standard answer that governments which spent more than they collected in taxation are on the road to ruin.

This argument is wrong, but it’s believed by people who, in another guise, are experts on money. Ferguson is an expert on the history of money; I prefer the work of Graeber, Martin and Gleeson-White, but his work on this front is scholarly. And yet he is entirely wrong about government finances, as were his interlocutors on the show, because they are all ignorant of the double-entry bookkeeping by which money is created.

Ferguson quipped that he had invented “Ferguson’s Law” recently: “any great power that spends more on interest payments than on defence won’t be great for much longer”. That led me to invent “Keen’s Law”: that “virtually everyone who claims to be an expert on money doesn’t understand double-entry bookkeeping”. The only exceptions—and I’m only being partially tongue-in-cheek here—are myself and Richard Murphy.

I’ve attacked this numerous times—frankly, I’m sick of the topic. But I’m forced to come back to it time and time again, because it is such a universally believed fallacy, and because “the experts” keep repeating it—leaving non-experts both misinformed and confused.

Each time I’ve covered this topic to date, I’ve started from the mainstream misconceptions: the “Money Multiplier” model of money creation, the “Loanable Funds” model of banking, etc. This time, I’m going to start from the right foundations, and see where they lead in understanding both money creation and banking.

Double-Entry

The fundamentals of double-entry bookkeeping were laid out by the monk Luca Pacioli in 1494.

His key passage was the following:

‘All the creditors must appear in the Ledger at the right hand side, and all the debtors at the left. All entries made in the Ledger have to be double entries—that is, if you make one creditor, you must make someone debtor.’ (Gleeson-White 2011, p. 93)

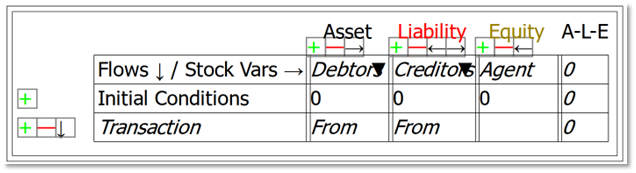

This is implemented in Ravel’s Godley Tables today—as well as in every ledger in every bank and company and government on the planet.

Accounting is difficult to master because you have to learn the conventions about when to classify something as a debit (DR) or a credit (CR). Ravel’s Godley Tables make this much simpler to understand by using another convention:

Ravel uses + and indicate - whether an account is increased or decreased by an operation; and

Ravel checks that every line obeys the equation that Assets-Liabilities=Equity, or Assets-Liabilities-Equity=0.

Ravel also enables an integrated view of the monetary system, by applying the rule that one entity’s financial asset is another entity’s financial liability.[1] The wedges you can see in the column headings check for any Liability that hasn’t yet been recorded as an Asset, and vice versa. It’s therefore very easy to build a complete model of the financial system in Ravel.

The simplest possible double-entry economic model

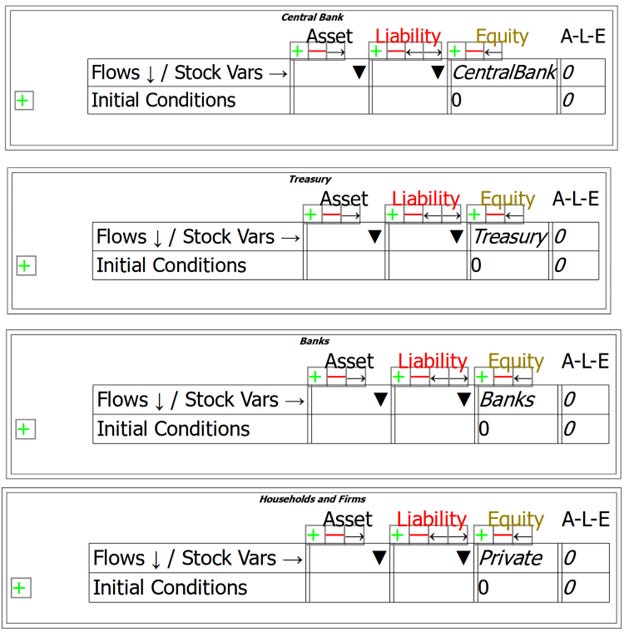

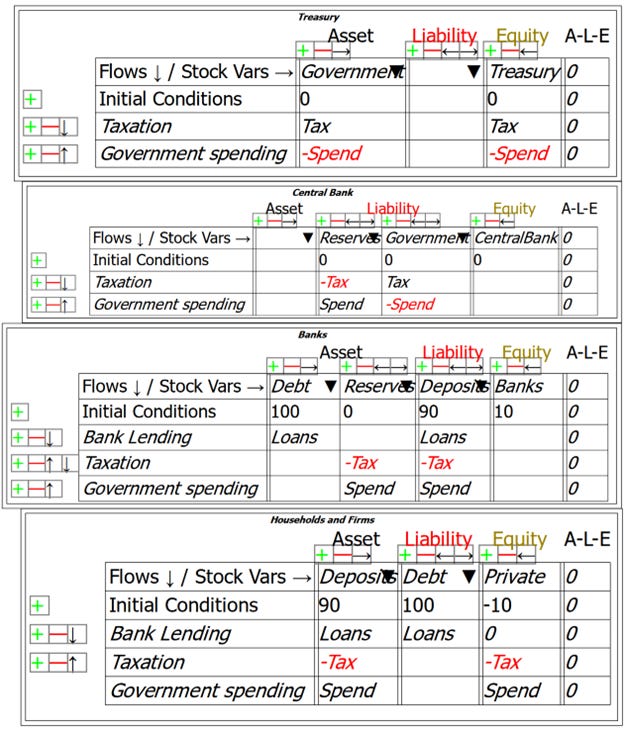

The real world has billions of people and firms, but the simplest possible model starts with four fundamental sectors: the banks, the private nonbank sectors (amalgamating Household and Firms), the Treasury, and the Central Bank. I start with a completely clean slate in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The 4 sector framework with no accounts or flows identified

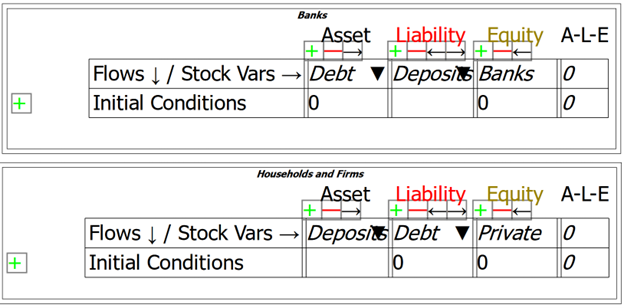

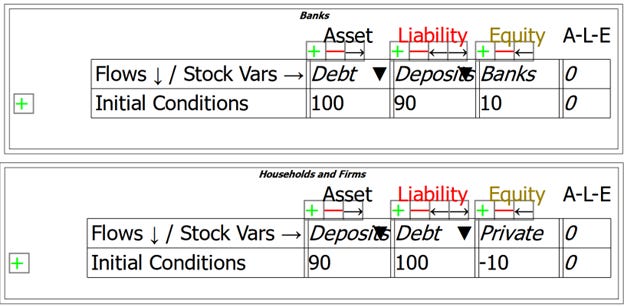

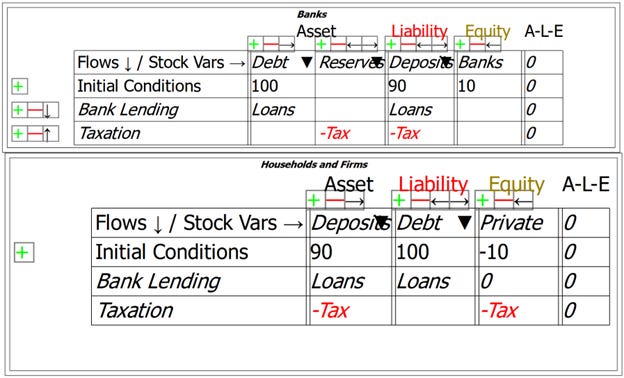

Now let’s add the basic accounts to explain private money creation: private debt, which is an asset of the banking sector and a liability of the private nonbank sector; and deposits, which are a liability of the banking sector and an asset of the private nonbank sector.

Figure 2: The two fundamental accounts for private sector money creation, Debt and Deposits

The initial conditions in a model are effectively the history of the model: the values that apply at some given point in time. Just as for the flows, the initial conditions also obey the rule that .

This leads to an insight from double-entry bookkeeping that you cannot get in any other way: since a financial asset is another entity’s financial liability, the sum of all financial assets and liabilities is zero.

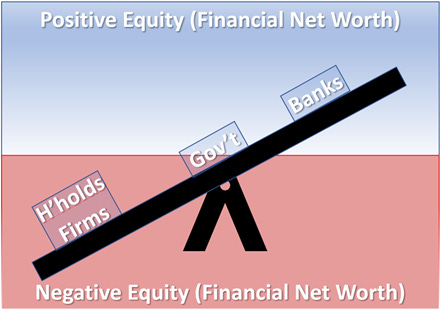

This is a “conservation law”: what applies to each transaction—that —also applies to the entire system. Therefore, if one entity in a financial has positive financial equity, the rest of the system has identical negative financial equity with respect to that entity.

In this sense, financial equity is like a see-saw: for one sector to be in positive financial equity—for it to be “up”—all remaining sectors must be in negative financial equity—they must be “down”—to precisely the same degree.

Figure 3: The see-saw of financial equity

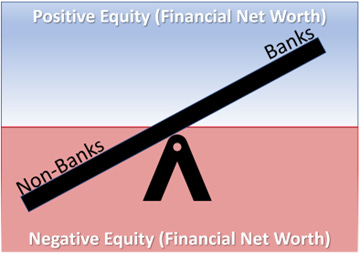

The initial conditions have to obey another rule. Nonbanks can operate with negative short-term equity, so long as they can service their liabilities. But banks must have positive short-term equity: their short-term Assets must exceed the value of their short-term Liabilities. This is both a legal requirement for registration as a bank, and an operating necessity: if a bank has short-term liabilities (mainly deposits) that exceed the value of its assets (mainly bank loans), then it is unable to fulfil all its obligations in the event of a bank run.

This leads to the second insight, that, in any financial system, since the banking sector must be in positive financial equity, the rest of the system is in negative financial equity of the same magnitude.

Figure 4: The banking sector must be in positive financial equity

In this initial private-sector-only model, this means that the non-bank private sector—households and firms—must be in negative financial equity.

Figure 5: Positive initial Equity for the banks, negative initial Equity for the nonbanks

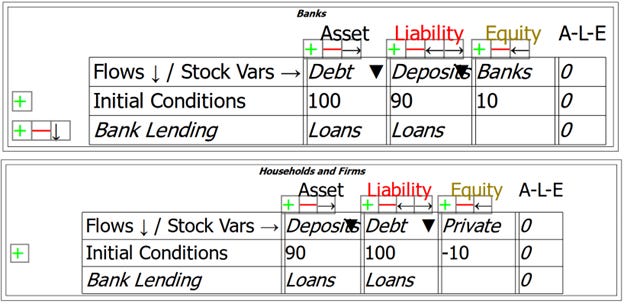

To explain private sector money creation in this model, we have to show the act of lending. Describing new bank loans as “Loans”, this shows the case made by Post-Keynesian economists (Moore 1979), and since endorsed by the Bank of England (McLeay, Radia, and Thomas 2014) and the Bundesbank (Deutsche Bundesbank 2017), that “Loans create Deposits”.

Figure 6: Loans create Deposits

That completes the absolute basics of private money creation, and notice that bank reserves play no role in it—in contrast to the textbook “Money Multiplier” model.

Reserves turn up when we consider the basics of government money creation. This is easier to see if we start with government taxation. Taxation reduces Deposits, and also reduces Reserves—the sum of the accounts of private banks at the Central Bank.

Figure 7: Adding government taxation to the model

As Figure 7 illustrates—and as is obvious to all of us when we fill out our tax returns—paying taxes reduces the Equity of the taxpayers. It takes money out of our Deposit accounts—our Assets—with no offsetting decrease in our Liabilities.

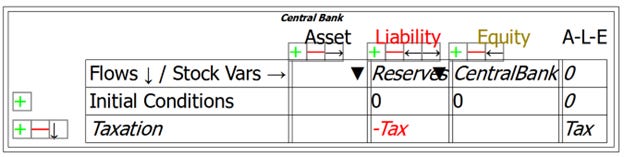

Unlike the private sector money creation process, this exposition isn’t complete with four entries for Taxation, because we have a new asset in the system—Reserves—which are not yet shown as a liability of some other entity. They are a liability of the Central Bank, as Figure 8 shows.

Figure 8: Showing Reserves as a Liability of the Central Bank

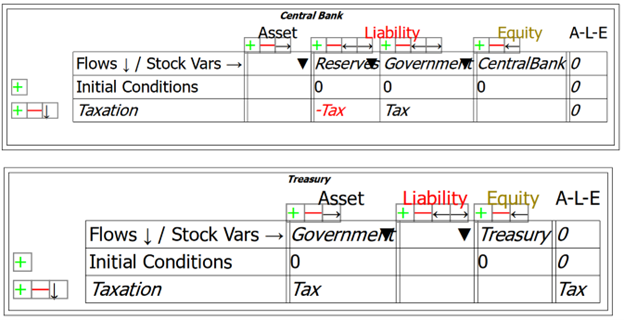

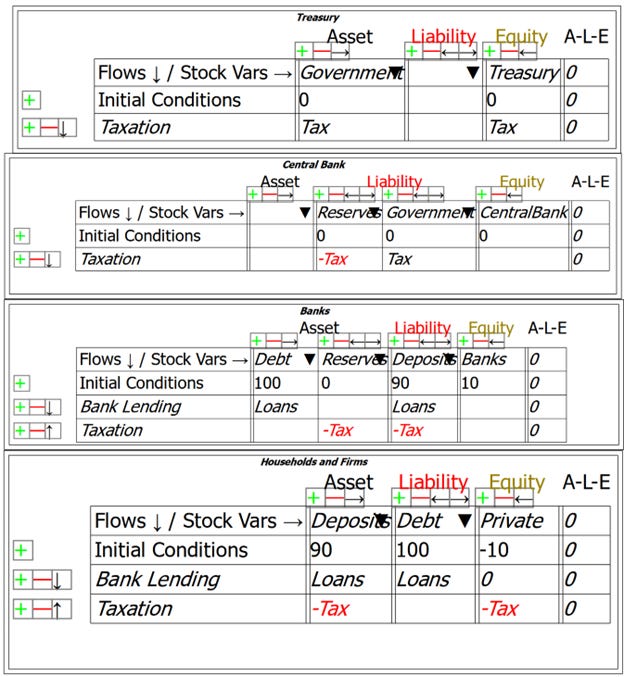

Of course, taxes are paid to the Treasury. They get to the Treasury through accounts that the Treasury has at the Central Bank. If we aggregate these accounts and call them “Government”, we can show that Tax reduces Reserves and increases the Government account. This is an Asset of the Treasury, so the Treasury’s Godley Table also has to be shown. This then gives us the situation shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Including the government’s accounts at the Central Bank

We still need the second entry on the Treasury’s Table: where can it go? It increases the financial equity of the Treasury—the mirror image of what it does to the private sector. Just as Taxation reduces the financial equity of the nonbank private sector, it increases the financial equity of the Treasury, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Completing the modelling of Taxation

Government spending, of course, has the exact opposite effect to government taxation: it reduces the financial equity of the Treasury, and increases the financial equity of the nonbank private sector. Figure 11 shows the full money creation picture:

the private sector creates private-debt-backed money if Credit is positive; and

the government sector creates fiat-backed-money if spending exceeds taxation.

Figure 11: Complete Basic Model of Credit and Fiat Money Creation

This points out the fallacy in conventional thinking about government deficits, that deficits are “a bug” of the economic system—a conventional view that Ferguson echoed when he said that “It leads to deficits every year, and not just in the bad years, which is wrong”.

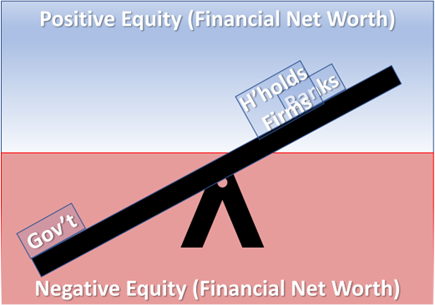

In fact, deficits are a feature of the system. Firstly, the government has to spend more than it takes back in taxation in order to create “fiat money”: money backed by the government’s authority, rather than by debt, as is the case for credit money. Secondly, if the government spends more than it takes back in taxation, it increases the financial equity of the non-government sectors. The banks are already in positive financial equity, as they have to be. But the non-bank private sector starts in negative financial equity—as shown by the initial conditions—and the only way it can get into positive financial equity is if government spending exceeds taxation. This necessarily involves the government going into negative financial equity.

The consequence of the preferred Neoclassical position that the government runs a balanced budget—the position adopted by everyone who doesn’t understand double-entry bookkeeping—is shown in Figure 12. A government that runs a balanced budget guarantees that the non-bank private sector will remain in negative financial equity.

Figure 12: A government that only spends what it taxes dooms the nonbank private sector to negative financial equity

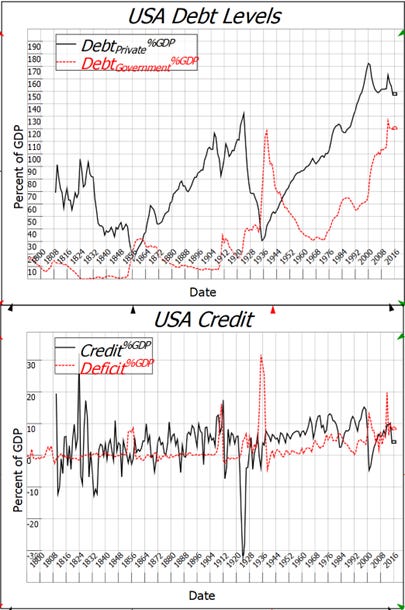

The consequences of a private sector that is in permanent negative equity can be inferred from comparing the 19th century, when US government debt was normally well below 30% of GDP, when government spending was typically of the order of 2-3% of GDP, and when it frequently ran surpluses to reduce its debt levels, to the post-WWII period, when government spending has typically been ten times as large, and deficits were the rule.

The private sector regularly got caught up in speculative bubbles, which caused what were then uneuphemistically called “Panics”. They would borrow money from banks to gamble on the latest economic innovation, resulting in a boom, which then crashed. As John Blatt notes, there was a serious financial crisis—with extended periods of negative credit as borrowers went bankrupt—even 8 to 15 years:

There was no government interference with the free market in those days; yet panics were by no means exceptional, unexpected events. On the contrary, the trade cycle with its recurrent panics was the normal pattern of nineteenth-century economic development. (Blatt 1983, p. 160)

Figure 13: Private and government debt, credit and deficits from 1810 till 2023

Since WWII, there has only been one period of negative credit—the “Global Financial Crisis”. In the 19th century, such experiences and worse occurred virtually every decade. There are many problems with post-WWII economic management—many of them caused by the Neoclassical obsession with reducing government debt, and lack of concern about private debt. But the sheer scale of government spending, and its counter-cyclical effect as tax revenues fall and government spending rises during downturns, has prevented the frequent panics that once characterized capitalism.

This is because the non-bank private sector can be in positive financial equity if the government goes into negative financial equity by running sustained deficits—not just “during bad times”. Despite the anti-deficit rhetoric from almost all commentators, the US has on average run a 3.2% of GDP deficit since the end of WWII.

Figure 14: Government negative financial equity enables the non-bank private sector to be in positive financial equity

People often rail at the thought of the government going into negative financial equity, because they implicitly think by analogy to their own situation. Negative financial equity is a stressful situation for a citizen or firm: why should it be any different for a government?

The answer is that your private liabilities are nothing like the liabilities of the government. Other people can’t use your liabilities to purchase goods and services, because your liabilities aren’t money. But the financial liabilities of the government are money. In fact, the borders of a country are defined as much by the region over which its government’s financial liabilities are accepted in commerce, as it is by where its customs agents operate, and where its army and navy patrol.

The government can also cope with negative financial equity because of its enormous nonfinancial assets. The apparatus of government—the legislative system, the army, the police system, the courts—are assets that only a government can have. The other nonfinancial assets that governments can create—public health and education systems, public infrastructure like roads, rail systems, even public spaces—can be created by government spending. The obsession with reducing the government’s financial liabilities actually undermines the creation of these nonfinancial assets. The building and maintenance of these nonfinancial assets can and should be financed in part by government money creation—which requires a government deficit.

I’ll finish with an obvious omission: I haven’t yet shown “government debt”. This was a deliberate omission, because I wanted to show that government money creation doesn’t need government debt.

That is obvious from the tables in Figure 11: in the real world, and in this model, money is primarily the sum of Deposit accounts at banks. The inflows to these accounts in are Loans and government spending; the outflow is Taxes. If Loans are positive, or if government spending exceeds taxation, money is created. Private debt is a necessity for private money creation, but government debt is not a necessity for government money creation.

Instead, government bond sales are necessary to prevent the Government’s account at the Central Bank from going into overdraft.

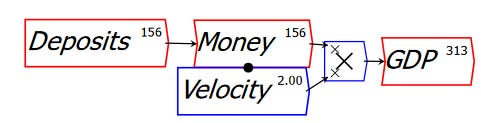

I illustrate this with a very simple simulation model, where I define the money supply as being equal to Deposits, and turning over at the Velocity of money—see Figure 15

Figure 15: A very simple “velocity of money” model of GDP

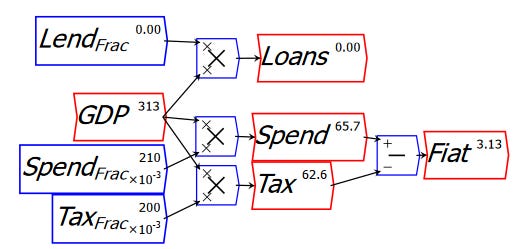

Next I define loans, government spending and taxation as fractions of GDP, which can be altered during a simulation—see Figure 16.

Figure 16: Lending, Taxation and Government Spending as fractions of GDP

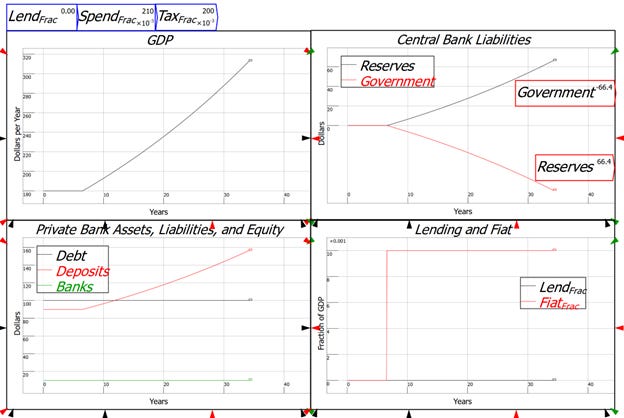

GDP grows if government spending exceeds taxation, but it has the side effect that the government’s account at the Central Bank goes into overdraft.

Figure 17: Money is created and GDP grows with government spending exceeding taxation

Private individuals face penalty rates of interest if they run up an overdraft, and they can be refused an overdraft: whether they get one or not is at the whim of the bank. Neither problem exists for the government, since it owns the Central Bank. In most countries, the Treasury doesn’t pay interest on bonds owned by the Central Bank (and any income earned by the Central Bank is remitted to the Treasury), and the Central Bank must grant the overdraft if the Treasury desires it.

However, running up an overdraft looks “shonky”. It can appear that the Government is “in hock” to the Central Bank, or that its spending in excess of taxation is irresponsible, since individuals who persistently do the same are being irresponsible.

There is a solution, however: for the Treasury to issue bonds and sell them directly to the Central Bank. I’ll cover that approach in the next instalment.

References

Blatt, John M. 1983. Dynamic economic systems: a post-Keynesian approach (Routledge: New York).

Deutsche Bundesbank. 2017. ‘The role of banks, non- banks and the central bank in the money creation process’, Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report, April 2017: 13–33.

Gleeson-White, Jane. 2011. Double Entry (Allen and Unwin: Sydney).

McLeay, Michael, Amar Radia, and Ryland Thomas. 2014. ‘Money creation in the modern economy’, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, 2014 Q1: 14–27.

Moore, Basil J. 1979. ‘The Endogenous Money Supply’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 2: 49–70.

[1] There are also nonfinancial assets. These are things like houses, shares, factories, roads, schools, etc.: they are assets to their owners and liabilities to no-one. Ravel handles these by treating them as both Assets and components of the Equity of the owners.

This video also landed in my feed -- from literally the first sentence I knew it was misguided. That said, I did learn some interesting history, particularly about the Rothschild's - but your point the monetary economics is all wrong.

Full disclosure...I'm a trained accountant who used to audit banks, so when I watch your explainers on the mechanics it all makes sense to me. However, I had to endure hundreds, if not thousands of questions before the "penny dropped" and double entry finally made sense. I wonder, is it fair to label those who don't double entry booking ignorant? Chancellor of the Exchequer, for sure. Historian in Ferguson, perhaps. The layman...arguable not. I wonder if the way to get through is by powerful story-telling rather tables and (very simple) equations. A-L-E=0 is so obvious to you and I, however to the man-on-the-street I get the feeling hieroglyphics make just as much sense.

Like everything that comes out of the TRIGGERnometry Youtube channel, it's staged propaganda. Notwithstanding the tedium, It is necessary to occasionally counter it, but important not to anticipate changing the minds of the propagandists themselves- this will never fail to frustrate. Take heart in the fact that these presentations are largely staged for the entertainment of angry young men who have already fallen victim to the pantheon of right-wing propaganda.

Although interest and defence spending both sit in the low-to-mid single digit percents, creating a "Fergusson's Law" undermines Niall's credibility by bringing into question his judgement in 'playing to the audience' in a place where more intelligent observers might also be watching.

Does anyone remember 'Trigger' from 'Only Fools and Horses'? Presenters Kisin and Foster are a great fit for the archetype- they clearly didn't consider the parallel when they named the channel!