Using accounting to prove the core propositions of MMT and Endogenous Money

I'm in the middle of a large consulting project on economics and climate change, and I'm also developing and delivering a set of seven "Mastermind" lectures, which you would have seen advertised on social media (a marketing firm is handling the messaging, which is why some people have thought it's not me putting out the messages—technically correct, but as a marketing amateur, I have left the marketing message to the firm). Consequently, I haven't posted a blog post here for a while: I've just been too busy on work that isn't yet published.

For this reason—and because it's the festive season, and I'd better give my supporters some sort of present in thanks for another year of supporting me—this blog post outlines the content I'll give in my next Mastermind lecture, on how money is created. I've chosen this topic because a supporter (or a correspondent on Twitter—I can't remember right now) said that, as an accountant, she needed an accounting explanation of how banks create money to persuade other accountants. So here it is.

I'll give more details in the lecture next week, but these are the core propositions I'll cover.

Firstly, money in our society is fundamentally the Liabilities (and short-term Equity) of the banking sector: the "L&E" side of the banking sector's ledger. Therefore, to create money, you have to increase the L&E side of the ledger. Given that banks are double-entry bookkeeping machines, this is only possible if you also increase the A—for "Assets"—side of the ledger simultaneously, and by the same amount.

This provides an incredibly simple way to work out whether a financial action creates money or not: to create (or destroy) money, a financial action must occur on both the Asset and the Liabilities/Equity side of the banking sector's ledger.

As I explain in the lecture—and the argument below—there are only 2 fundamental operations that qualify in a domestic economy:

Banks lend out more than they take back in repayments; and

Governments spend more than they take back in taxes

There are also ancillary activities that cause money creation or destruction:

Interest payments on government bonds; and

Sales of bonds by the banking sector to the non-bank public

My Minsky software is, by far, the best way to illustrate this, because the Godley Tables in Minsky are based on double-entry bookkeeping. I'll start with bank lending, and then consider government spending.

Bank Lending

The absolutely simplest model of bank lending is shown in Figure 1: net lending (which can be positive or negative) is Credit dollars per year, the non-bank public pays Interest on outstanding Loans, and the banks spend on the non-bank public (SpendBanks).

Figure 1: The basics of bank lending

Notice that Reserves, which are an essential part of the mainstream economic model of banks—the "Money Multiplier", in which banks lend from Reserves—play no role at all here. In countries where a "Required Reserve Ratio" still exists, banks could be required in the aggregate to borrow Reserves from the Central Bank; but most countries have abolished RRRs, and QE has swamped banks with excess reserves in any case.

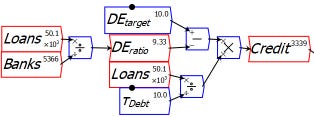

A more realistic control on bank lending is that banks may require themselves to not be too heavily geared (though they threw this caution to the wind during the Subprime Bubble). Banks would then have a target Loans to Equity ratio, which controls their lending, but even this can allow for indefinite money creation by bank lending. In Figure 2, I model bank lending as controlled by a target growth rate for loans (Debt) and a desired Loans to Equity ratio (DEratio).

Figure 2: Bank lending controlled by a target loan to equity ratio and target loan growth

It's possible for lending to continue forever with this control, since the payment of Interest increases the banks' equity. As the simulation in Figure 3 shows, so long as Interest exceeds Spend, this is a formula for ever-expanding bank-created money and debt.

Figure 3: Ever-expanding credit with a debt to equity driven lending regime

Banks therefore create money by expanding their Assets and Liabilities simultaneously. The situation is rather different for government money creation: governments create money by going into negative equity, which is matched—dollar for dollar—by an increase in the positive equity of the non-government sectors.

Government Taxation and Spending

Though Reserves play no role in bank lending (contrary to mainstream economics), they play an essential role in government taxation and spending. Figure 4 shows that taxation reduces bank deposits and spending increases them—which shouldn't be controversial, but given the confusion that mainstream economics has caused, it might well be! How can government spending in excess of taxation create money, when—according to economics textbooks—the government has to borrow from the public in order to spend?

Figure 4: Taxation and spending entered against Deposits only

Because the textbooks are wrong, that's why (as the Bank of England has already said they're wrong about bank lending—see "Money creation in the modern economy"). As a simple matter of accounting, paying taxes reduces bank deposit accounts, and government spending increases them. Government spending thus creates money.

Now, how do we balance these entries in double-entry terms? The only candidate for balancing the accounts is Reserves: just as net government spending creates Deposits, it also creates Reserves—see Figure 5.

Figure 5: Taxation and spending balanced by matching entries on Reserves

But where do the additional Reserves come from? To see that, we have to complete the modelling of the financial flows between the four sectors in this model: the Banks, the non-bank Public, the Central Bank, and the Treasury. Minsky makes this easy to do, by understanding that every (financial) Asset is another entity's Liability. All you have to do as a modeler is, when there isn't an obvious matching Asset/Liability pair into which a flow should go, record it against the entity's equity instead. This given you Figure 6.

Figure 6: The general model allocating all Assets and Liabilities

To answer the question "where do the additional Reserves come from?", strictly speaking, they come from the Treasury's account at the Central Bank—which I've described as "CRF" for "Consolidated Revenue Fund". But without including government bond sales, if spending exceeds taxation for a sustained period, this account will go into overdraft. This is shown in Figure 7, where I've made both taxation and spending functions of GDP that are under government control (the real world is far more complicated of course, but this suffices to show the basic structure of government finances). Central Bank liabilities remain constant, but this involves rising Reserves and a negative balance in the CRF.

Figure 7: The model without government bond sales

Is that a problem for the government, in the same way that an overdraft is a problem for a bank customer? No, for the simple and fundamental reason why the government has a unique position in a monetary system: the Treasury, on behalf of the government, owns the Central Bank. If any of us spend without regard to what's in our bank deposit account, we'll pretty soon experience punitive interest rates, and ultimately bankruptcy. But the government could continue running a negative balance in its account at its bank for as long as it wished to.

At this point in the model, money creation is the sum of the entries in Deposits and Banks (the short-term equity position of the banking sector). This sum is:

Credit is obviously the contribution of the banking sector, which comes from its equal expansion of its Assets and Liabilities. SpendGov -Tax is obviously the government's contribution, and this is identical in magnitude to the change in the government's equity position, but opposite in sign: the government creates money to the extent to which it creates negative equity for itself. This creates an identical increase in the positive equity of the non-government sectors:

This is the key functional difference between private (credit) and government (deficit) money creation: banks create money by expanding their Assets and Liabilities identically, with no effect on their Equity; governments create money by increasing their negative equity.

Many people seem to object to this "on principle": "The government shouldn't be in negative equity, dammit!". But this is just how government money creation works, and since we're dealing with financial assets—which are one entity's claims on another entity—then if the government isn't in negative equity, the non-government sectors must be instead.

Since banks, by law, have to have positive equity (otherwise they are bankrupt), then if the government was also in positive equity (or even zero), the non-bank public would have to be in negative equity. But if the government runs sustained deficits, both the banks and the non-bank public can be in positive equity. This is why it's vital to look at the entire system, something that mainstream economics does not do (they don't even model banks in their macro models, so they don't have a clue how the overall financial system operates).

This especially applies to how they think about government bond sales, which they think involves governments taking money from the public, or adding to the demand for money. No they don't.

Bond Sales and Bond Interest

Bond sales are mandated in almost all countries, by laws that require the government not to have a negative balance in its CRF (consolidated revenue fund) at the Central Bank. This is normally expressed as a rule that the government has to issue bonds equivalent to the deficit plus interest on outstanding bonds. Some superficial thinkers—and there are a lot of them!—think that this means that the government can't spend before it raises revenue from taxation and bond sales. But in fact, the dynamics of the system mean that (a) the deficit creates the funds—Reserves—that are used to buy the bonds, and (b) given some net buying of bonds by the Central Bank, and the fact that bonds are sold very frequently—normally at weekly bond auctions—there is always more than enough Reserves (a stock) on hand to cover any deficit spending (a flow), whether bond sales lead, lag, or are contemporaneous with the deficit.

Bond sales add quite a bit of additional complexity to the model—see Figure 8. Three new accounts are needed, for Bank, Central Bank and Public holdings of bonds; interest is paid to Banks and the Public on bonds (though not, normally, to Central Banks—and in the countries where this applies, the interest income is ultimately remitted to the Treasury.

Figure 8: The accounting tables for all sectors

The key transaction here is the sale of bonds by Treasury to the banks, and as noted this is equal to the deficit plus interest payments on bonds—see Figure 9

Figure 9: Primary sales of bonds equals the deficit plus interest on outstanding bonds

The Central Bank is always undertaking what are called "Open Market Operations" (OMO) with banks in order to maintain its target interest rate on bonds, and Central Banks always have substantial holdings of Treasury Bonds in their Assets. In this model, I'm assuming that net Central Bank purchases from private banks are equal to the interest paid on outstanding treasury bonds—see Figure 10. In practice, they can be lower than this, or as high as the total issuance of bonds by the Treasury: the Central Bank has a limitless capacity to buy bonds by crediting the accounts of private banks—their Reserve accounts.

Figure 10: Modelling Central Bank bond purchases equalling the interest on existing bonds

Bond sales to banks precisely counter the deficit and interest payments on outstanding bonds, so that the CRF remains constant; the purchase by the Central Bank of bonds equivalent to the interest payments on bonds means that Reserves grow while the CRF remains constant. The Treasury therefore always has enough funds on hand to finance its spending while maintaining a positive balance in the CRF, as required by law. Banks are also always going to be willing to buy these bonds, because they can swap Reserves—which earn either no interest, or a lower rate of interest than bonds yield (with the rate set by the Central Bank)—for Bonds. They can then trade these bonds, which they do on the world's largest financial market, and the interest payments from the government partly cover the cost of running the country's payments system.

Figure 11: The full model, showing that Reserves more than equal the annual deficit

Conclusion

Frankly, none of this should be controversial: it is, as shown in this post, simply a matter of accounting. The controversy comes from mainstream "Neoclassical" economists—aided and abetted by Austrian economists, gold bugs, and the like—not understanding how the monetary system works, because they don't understand double entry bookkeeping—let alone. think in terms of it when modelling the economy.

Instead, thanks to their ignorance, we have endless "crises" over debt ceilings, too much private credit money creation thanks to too small government deficits, austerity crippling economies as it results in governments not investing sufficiently in infrastructure and welfare, and "puzzling" low growth rates for economies that thought that austerity would unleash private sector creativity, when in fact it hampered it by reducing the growth of the money supply.

Will the collective We ever understand this? Frankly, I doubt it. I've witnessed decades of delusion on these issues, and I reckon I'll witness years more, despite the success of MMT in getting good sense on money creation into the public debate.

Merry Xmas and Happy New Year everyone. Here's hoping, against experience, that 2023 won't be worse than 2022.

This software and model accounting for money flows and interrelationships provides a platform for reasoned policy development. Why did we have to get to 2022 to get it? Thanks Professor Keen and may you enjoy a deserved Merry Xmas and a fantastic New Year