Trump is Right on Powell–but for the wrong reasons

Powell suffers from Neoclassical Derangement Syndrome, not Trump Derangement Syndrome

Trump is now describing Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve Chair, as an idiot, and calling on him to resign:

Now, you might think that, if Powell is so stupid, then an idiot must have appointed him in the first place. And Obama, whom Trump also thinks is an idiot, did make Powell a Governor of the Federal Reserve in 2011.

But who promoted Powell to be the Federal Reserve Chair? That was Donald Trump, in 2017:

So was Trump wrong in 2017? Or has Powell, since he was appointed, fallen prey to “Trump Derangement Syndrome”? That’s Trump’s preferred explanation:

But in fact, the problem is much deeper. Powell doesn’t suffer from “Trump Derangement Syndrome”: he suffers from “Neoclassical Derangement Syndrome”. Powell is a lawyer by training, but he follows the advice of The Fed’s economists. They are all Neoclassical, and the models they build to guide The Fed are simply crazy.

What Central Banks think they’re doing

The Fed’s economists use what they call “Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium” models, to determine how to set interest rates.

The Fed published a simplified model to explain how they work in 2010–two years after these models had completely failed to predict the Global Financial Crisis.

They admit this in the paper, when they say that:

“Recently, the 2008 financial crisis has highlighted one key area where DSGE models must develop: the inclusion of a more sophisticated financial intermediation sector.”

(I’ll explain what that jargon–“a more sophisticated financial intermediation sector”–means, and why it shows that they are clueless about the banking system, in a later post).

The paper opens with the key property of these models, that they “emphasize the dependence of current choices on expected future outcomes.”

The key variable which they think affects inflation is, therefore, inflation itself–but not current inflation, or past inflation, but the inflation rate that the public expects to apply in the future.

Now, how do they work that what the public expects? Do they take surveys? Yes they do. But in DSGE models themselves, economists assume that consumers form their expectations using the same model that economists use:

We assume that these expectations are rational, meaning that they are based on the same knowledge of the economy … as that of the economist constructing the model.

Take a look at some of these equations and assumptions in this model, and ask yourself whether they’re in your head. And yet, if they’re not, then the model is already wrong:

And what do they mean by “these expectations are rational”? This is where things get crazy.

Not only do economists assume that everyone has a model of the economy in their heads that is the same as the model they have developed, they also assume that this model is an accurate predictor of the future. Bear in mind that this is after they’ve already admitted that their models completely failed to predict the Global Financial Crisis.

Why these models were invented

Why do economists make crazy assumptions like this? It’s because, believe it or not, these economists, who work for the government, believe that the market works best if the government does nothing. The idea of “rational expectations” was invented to assert that government policy couldn’t work, because the public will know what the impact of government policies would be, and then it will act to counter them.

This became known as the “Policy Ineffectiveness Proposition”: that there is no way that government fiscal policy can work, because the public will save when the government runs a deficit, and spend when it runs a surplus, thus rendering government policy ineffective.

This happens, according to Robert Barro, because households know that higher spending now means higher taxes in the future. So, when the government runs a deficit, households save money to pay future taxes, and aggregate demand remains the same.

Someone asked Barro what happens if households think that those taxes are going to be levied in the far future? What if they only plan a few years ahead, and therefore they don’t expect that they’ll have to pay those taxes?

Barro conceded that this would mean a budget deficit would stimulate the economy now. But then he countered that:

The argument fails if the typical person is already giving to his or her children out of altruism…

a network of intergenerational transfers makes the typical person a part of an extended family that goes on indefinitely. In this setting, households capitalize the entire array of expected future taxes, and thereby plan effectively with an infinite horizon.

This is a ridiculous argument, not only because no-one can “plan effectively with an infinite horizon”, but also because Neoclassical economists are the very prophets of self-interest. When an economist appeals to altruism to support an argument, you should know there’s something fishy going on.

The fishy thing goes right back to the person who dreamt up the idea of “rational expectations” in the first place, John Muth, way back in 1961.

Why their foundations contradict Neoclassical Economics

Firstly, Muth assumed that Neoclassical economic models are correct. In his words, he declared that:

expectations, since they are informed predictions of future events, are essentially the same as the predictions of the relevant economic theory.

This is already gaga. I’m happy to assume that my own models are reasonably accurate about the future, given that they let me predict the Global Financial Crisis before it happened. But I’m not about to assume that everyone on the planet has that same model in their heads!

People’s beliefs differ wildly, and if your theory relies on them all having the same beliefs–especially if they are your beliefs–then there’s something seriously wrong with you. Worse still, if you believe that your beliefs are correct, and that everyone shares them, then you are not rational. You are mad.

That becomes obvious very early in Muth’s paper, when he says that:

Information is scarce, and the economic system generally does not waste it.

Hello? Unless information is free–and information about the future, no less–the economic system would definitely waste part of it, because paying for all of it would be, according to Neoclassical economic theory, irrational.

The Neoclassical definition of rational behaviour is to do something until the gap between its benefits and costs is maximized. In this case, the rational consumer should buy “information” only up until the point that its marginal utility equals its marginal cost. Buying any more information than that is irrational.

The proper application of Neoclassical theory therefore makes this an argument, not for the perfect foresight “rational expectations” that Neoclassical economists use, but for bounded rationality.

Instead, Muth effectively assumes that information–and information about the future, no less–is both complete, and free. This is complete nonsense, but it’s also typical nonsense for Neoclassical economists.

At numerous points in their analysis, Neoclassical economists will reach a logical dead end, and then make “the can opener assumption” to get over the problem.

The “can opener” assumption, if you haven’t heard it, is a joke about a physicist, a chemist, and an economist, who survive a shipwreck together. They’re on a desert island, with nothing to eat but cans of baked beans that washed up from the wreck.

The chemist says that he can make a fire using nearby palm trees, and heat the cans enough for them to explode.

The physicist says that he can work out the trajectory of the beans, so that they can gather and eat them.

The economist says “Hang on guys, you’re doing it the hard way. Instead, let’s assume we have a can opener”.

The Fed’s “Euler” Equations Don’t work

DSGE modellers call their key equation “the Euler Equation”, and it has been an empirical failure. Google “empirical failure of the Euler equation” and you’ll get a result like this:

The Fed authors admit this in their own paper:

This failure to match the data highlights the main empirical weakness of our model… As in most of the DSGE literature … Standard specifications of a Euler equation … provide an inaccurate description of the observed relationship between the growth rate of consumption … and financial returns, including interest rates.

But then, rather than admitting that the whole idea of people accurately predicting the future is crazy, and finding some other way to model the economy, the authors then state that:

Improving the performance of the current generation of DSGE models in this dimension would be an important priority for future research.

You can’t improve something which is, at its core, crazy. You need a whole different theory instead. Fortunately, there are theories, developed by non-Neoclassical economists, which are more realistic.

The Real Drivers of Inflation

Back in the 1950s, the Polish engineer turned economist Michal Kalecki worked from economic definitions to identify the three main drivers of inflation:

Money Wages;

Output per Worker; and

The markup that firms apply to wages to set prices

His formula was that inflation equals the sum of changes in money wages, plus changes in markups, minus the increase in output per worker.

The real drivers of inflation are therefore the costs of production, and the contest between workers and employers over the distribution of income. Let’s look at these in my Ravel software–which you can get from https://patreon.com/ravelation.

Firstly, you can see that, up until 1974, workers generally had the upper hand: money wages increased faster than inflation, so that real wages rose.

From then until the Internet Boom began in 1993, money wages rose more slowly than prices, so that real wages fell. From the early 80s on, markups often rose more rapidly than inflation, and inflation was only checked by large increases in output per worker (the lower the red line is in the graph, the more increased output per worker reduces inflation).

If we now zoom in on the period around the Covid crisis, we can see that the main contributors to inflation peaking at just over 6% in 2022 were money wage increases and a decline in output per worker–thanks to the supply bottlenecks caused by Covid–while markups actually fell.

The fall in inflation since 2022 has been mainly due to output per worker rising once more. This more than countered money wage rises exceeding inflation, and rising markups.

This analysis implies that contests over the distribution of income–played out through wage rises by workers, and markups by firms–are the crucial determinants of the rate of inflation, as is increases in output per worker generated by technological progress.

The Fed’s argument that it’s all determined by expectations is no better than a belief that fairies set the rate of inflation. Even “Nobel” Prize winners, like Robert Solow and Paul Romer, feel this way. As Paul Romer said:

In response to the observation that the shocks are imaginary, a standard defense invokes Milton Friedman’s methodological assertion from unnamed authority that “the more significant the theory, the more unrealistic the assumptions.” More recently, “all models are false” seems to have become the universal hand-wave for dismissing any fact that does not conform to a favorite model. The noncommittal relationship with the truth revealed by these methodological evasions and the “less than totally convinced ...” dismissal of fact goes so far beyond post-modern irony that it deserves its own label. I suggest “post-real.”

Trump needs an economist who focuses on the real-world determinants of inflation, not a Neoclassical who believes the fantasy that people can predict the future.

I’m not that expert: complex systems, macroeconomics in general, the monetary system and climate change are my main interests. But I do know three people who have specialised in inflation that Trump could appoint.

Three realistic economists that Trump could appoint

One is Isabella Weber. Her research implies that wage-price agreements can keep inflation under control.

Another is Blair Fix–though Trump would need to acquire Canada to hire him. He does some of the best and most detailed empirical research out there, without being hobbled by fantasy beliefs. He breaks inflation down into the many changes in the prices of individual commodities, and how they affect different social groups.

Finally, there’s a new arrival on the data analysis front, James Young. He’s taken my credit-based analysis of economic cycles, and shown that credit money creation, rather than government spending, is the main monetary determinant of inflation. Such a pity that he’s an Australian: maybe Trump could waive the tariffs and import him?

Any of these people would be far better than Powell. They would be far better than any Neoclassical economist he might be replaced by, if, as is highly likely, Trump sticks to the mainstream when he makes his choice.

You can find Isabella Weber’s work at https://www.isabellaweber.com/

Blair Fix website is https://economicsfromthetopdown.com/

James is on Twitter at https://x.com/JamesYo43532848.

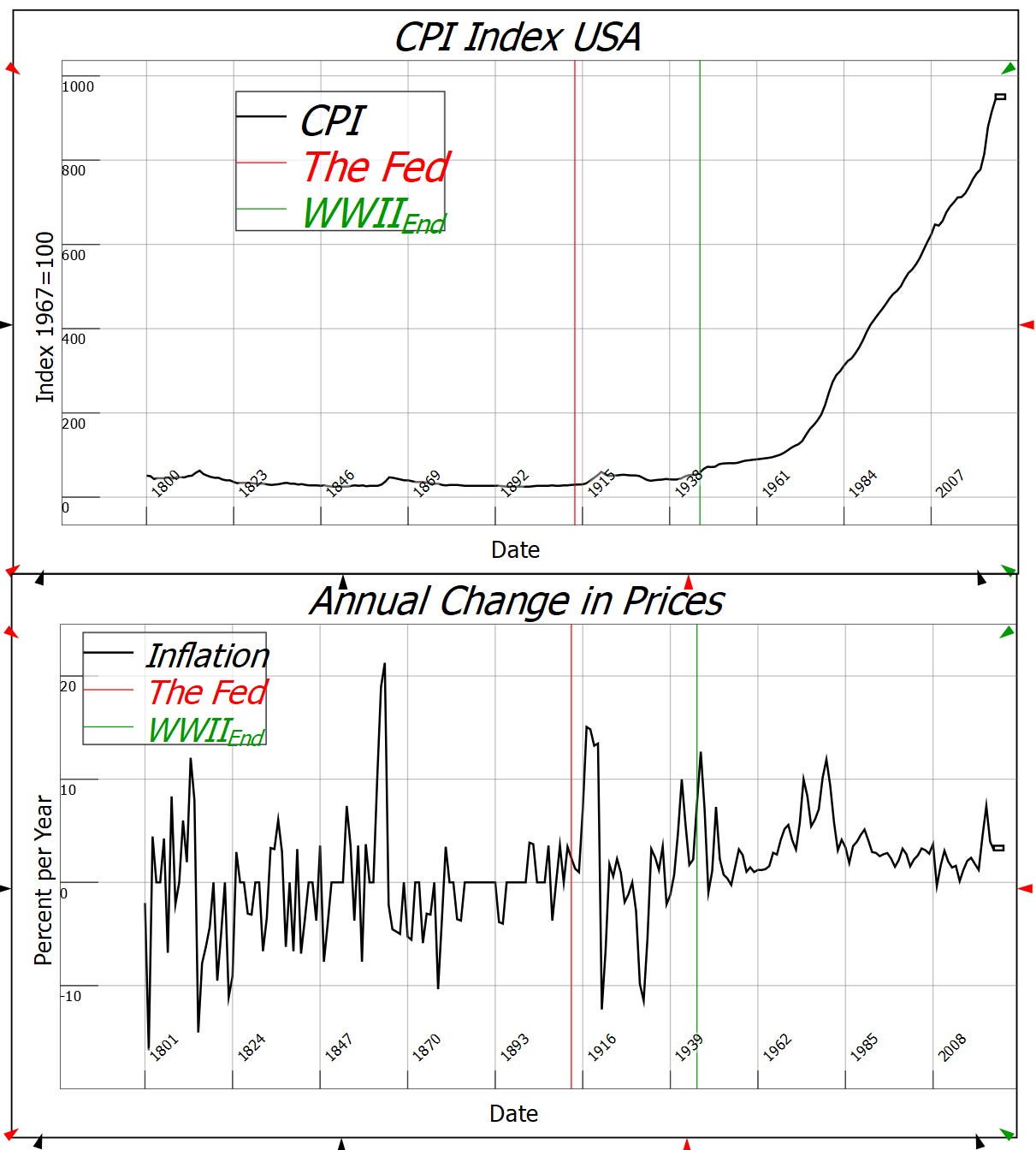

Lastly, don’t think that completely eliminating inflation would be a good thing. Most people look at a chart like this–the CPI for the USA between 1800 and today–and think that the 1800s were the “good olde days” of price stability, before the nasty Fed and Big Government gave us never-ending inflation.

In fact, if you zoom in, you can see that prices in the 1800s–before the Fed, and up till the start of WWII–were extremely volatile.

Inflation was actually higher in the 1800s than it has been since WWII. The difference is that, in the 1800s, there were also significant bouts of deflation, which always accompanied financial crises. The Post-War system, mainly because government is roughly ten times the share of GDP that it was in the 1800s, has avoided the nightmare of debt-deflations.

Continuous low-level inflation, which is what we’ve experienced since 1945–with the sole exception of the higher but still moderate inflation levels caused by OPEC in the 1970s and 1980s–is a lot better than regular bouts of deflation. Be careful what you wish for.

"up until 1974, workers generally had the upper hand". I would say they had an 'even hand'. From American data https://www.epi.org/productivity-pay-gap/ worker share of productivity exactly tracked productivity increase from 1947 to 1960, and was only slightly divergent from 1960-74. I imagine this divergence was a result of innovations such as containerisation and ro-ro shipping of vehicles allowing international trade to become much more competitive. There is a sharp turn in 1974 as you say. Financialisation became the big stick to beat the workers with, since it was possible to make money without the vicissitudes of industry. This probably also accounts for the contemporaneous fall in productivity from 2.5% p.a to 1.4% p.a. with all the brightest and most ambitious management material (as well as capital) being sucked into the finance sector rather than the industrial.

Pretty much the sole purpose of anything 'real' in this world such as natural resources, goods and non-financial services, land and housing only exist to provide a starting point upon which fictitious capital can be hypothecated. What could possibly go wrong?!

All of your critiques of neo-classical economic theory are valid. Full stop. But the deepest problem with it is the entire idea that "free" market theoretics enables COMPLETE FREEDOM...which in the human universe is a dangerous delusion...because the little thing known as ethics cannot RATIONALLY be escaped. So you're also correct that economic theory and economic actions must be rationally bounded.

"Free" market theoretics is a delusion and a misnomer for its actual reality which is alternately goosed and strangled unstable dominating monopolistic financial and monetary chaos...and the solution to that rather long adjective is to integrate the new monetary paradigm of Direct and Reciprocal Monetary Gifting into the Debt Only system with a 50% Discount/Rebate policy at retail sale instead of using the current ham handed methods utilized by neo-classically deluded central banks...and then rationally and ethically regulate the economy instead allowing a suave or unabashed financial and economic oligarchy to dominate the general populace for another 6000 years or maybe another 50 years until climate change kills off 4-5 billion of us.

We must "go deep, go long" on APPLIED conceptual/paradigmatic analysis because anything other than an ACTUAL paradigm change gets gamed and the clock is ticking very loudly.