Trade, Tariffs, and Coming up Trumps

This is Chapter 11 in my forthcoming book "Money and Macroeconomics from First Principles for Elon Musk and Other Engineers"

This chapter was written in the middle of a trade war initiated by the Trump administration in the United States on April 2nd. Trump introduced it as “Liberation Day”: “April 2nd 2025 will forever be remembered as the day American industry was reborn.”[1]

It has turned out to be more Litigation Day than Liberation day. Tariffs have been announced, increased, reduced, and put on hold. But leaving aside these chaotic events, the objective of Trump’s policies has always been to eliminate America’s trade deficit. This was clearly articulated by the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors, Steve Miran (Miran 2025). His justification was that being the reserve currency overvalues the US Dollar and puts American manufacturing at a disadvantage:[2]

the reserve function of the dollar has caused persistent currency distortions and contributed, along with other countries’ unfair barriers to trade, to unsustainable trade deficits. These trade deficits have decimated our manufacturing sector and many working-class families and their communities, to facilitate non-Americans trading with each other…

He acknowledges that the US dollar’s reserve currency status enables the USA to dominate the global financial system, but he asserts that “our financial dominance comes at a cost”:

While it is true that demand for dollars has kept our borrowing rates low, it has also kept currency markets distorted. This process has placed undue burdens on our firms and workers, making their products and labor uncompetitive on the global stage, and forcing a decline of our manufacturing workforce by over a third since its peak1 and a reduction in our share of world manufacturing production of 40% …

Miran defends tariffs, and rejects the conventional economic argument that exchange rate movements will eliminate trade deficits:

One reason the economic consensus on tariffs is so wrong is because nearly all of the models that economists use to study international trade assume either no trade deficits at all, or assume that deficits are short-lived and quickly self-correct through currency adjustments. According to standard models, trade deficits will cause the dollar to weaken, which reduces imports and boosts exports, eventually wiping out the trade deficit…

However, that view is at odds with reality. The United States has run current account deficits now for five decades, and these have widened precipitously in recent years, going from about 2% of GDP in the first Trump Administration to a high of nearly 4% of GDP in the Biden Administration2. And this has happened all while the dollar has appreciated, not depreciated!

The long run is here, and the models are wrong. One reason is that they fail to account for the U.S. provision of the global reserve currency. Reserve status matters and, because demand for the dollar has been insatiable, it has been too strong for international flows to balance, even over five decades.

He also asserts that the trade deficit benefits wealthy Americans, at the expense of those who used to rely upon manufacturing for their incomes:

This overvaluation has weighed heavily on the American manufacturing sector while benefiting financialized sectors of the economy in manners that benefit wealthy Americans. (Miran 2024)[3]

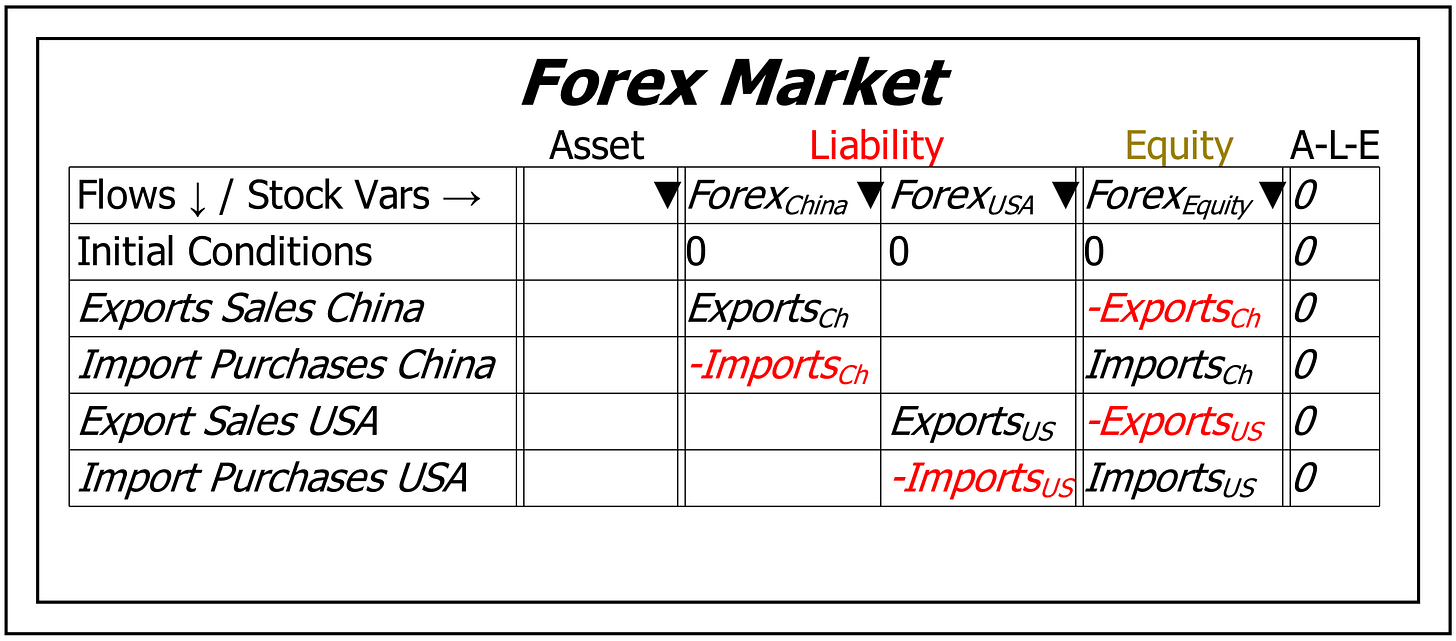

The US has indeed been running a sustained balance of trade deficit. The last time the US had a trade surplus was briefly in 1975—see Figure 43.

Figure 43: US trade deficits and the surpluses of some of its major trading partners. Data sourced from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BN.GSR.GNFS.CD and https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD

The models Miran rightly criticises here are typical Neoclassical models in which trade is treated as a barter operation, and monetary factors are ignored. They therefore cannot assess the impact of sustained trade imbalances on monetary factors, or of monetary factors on trade itself. It is, however, easy to model the essentials of the monetary impact of trade imbalances in Ravel, using its Godley Tables.

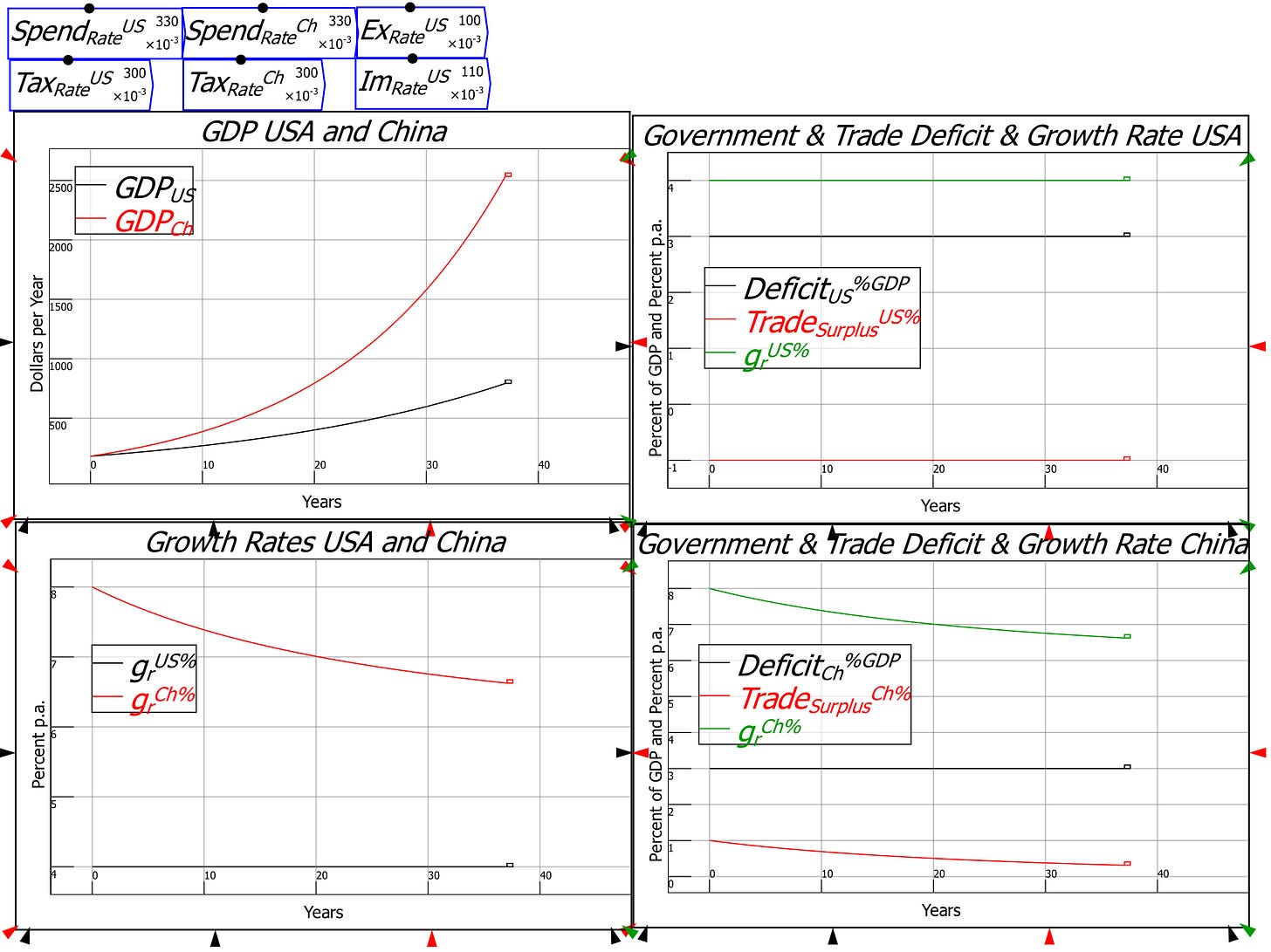

As shown in Chapter 2, “The First Principles of Money” (page 8 et.seq.), a government budget deficit creates money. Similarly, a trade surplus—or more correctly, a surplus on the balance of payments[4]—also creates money.

The logic in both cases is obvious: government spending increases deposit accounts while taxation reduces them; and import purchases reduce deposit accounts while export sales increase them. Therefore, at the level of the private banking system, and in the aggregate, the effects of a government deficit and a trade surplus on the money supply are identical—see Figure 44.[5]

Figure 44: The basics of money creation by government deficits and trade surpluses: private banks perspective

The two processes diverge at the level of the Central Bank. A government deficit adds to Reserves by transferring funds from the Treasury’s account at the Central Bank to the Reserve accounts of the private banks. A trade surplus adds to Reserves by increasing the Central Bank's holding of foreign reserves. Figure 45 glosses over the currency conversion involved, in that the foreign exchange holdings of the Central Bank are valued in US dollars, but an export surplus involves a net increase in the value of foreign currencies held by the Central Bank.

Figure 45: The basics of money creation by government deficits and trade surpluses: Central Bank perspective

Government spending in excess of taxation involves the government going into negative financial equity, as explained in Chapter 4 (page 20 et. seq.). There is no limit to the capacity of governments to do this around the world, so the aggregate of all government deficits can be negative or positive—and in general, despite the “balancing the books” rhetoric which politicians across the globe use, the sum of all government surpluses across the world is always negative.

A trade surplus or a trade deficit is different because, in the aggregate, for all countries the sum of all trade deficits is zero.

However, countries can and have run sustained trade deficits for decades—notably the USA—while other have run sustained trade surpluses—such as China. Deficit countries reduce their holdings of foreign currencies, while surplus countries increase them: see Figure 46. Only the USA is an exception to this rule because its domestic currency is used for international trade—so it can create the currency needed for international trade in a way that no other country can.

Figure 46: A very simple and stylized picture of the ForEx market

Figure 47 shows the private sector impact of both government deficits (and surpluses) and trade surpluses (and deficits). Government deficits increase the net financial worth of the private sector, as shown already in Chapter 4. A trade surplus has the same effect. Likewise, a trade deficit reduces the net financial worth of the private sector.

Figure 47: The private sector impact of trade imbalances

As shown by Equation , an export surplus increases the net worth of the private sector, just as a government deficit does (red entries cancel out at the level of the private sector).

We therefore get Equation . A government deficit—where government spending exceeds taxation—increases the net worth of the private sector, and an export surplus—where exports exceed imports—does the same:

The reciprocal nature of trade—in that an export for one country is an import for another— enables us to simulate the impact of a government deficit and a trade deficit for one country, and a government deficit and trade surplus for another country. The former is the customary situation of the USA, burdened as it is by the responsibility of providing the world’s trading currency. The latter is the customary situation of China, one it has pursued from the outset of the post-Mao economic regime instituted by Deng Xiao Ping.

A simple model of the impact of a bilateral trade imbalance can now be built. Given the current emphasis on the US-China trade imbalance, I have used “US” for the deficit countries and “Ch” (China) for the surplus countries. Figure 48 models imports and exports as a fraction of GDP, and shows the exports of one country or bloc (“US”) as the imports of the other (“Ch”).

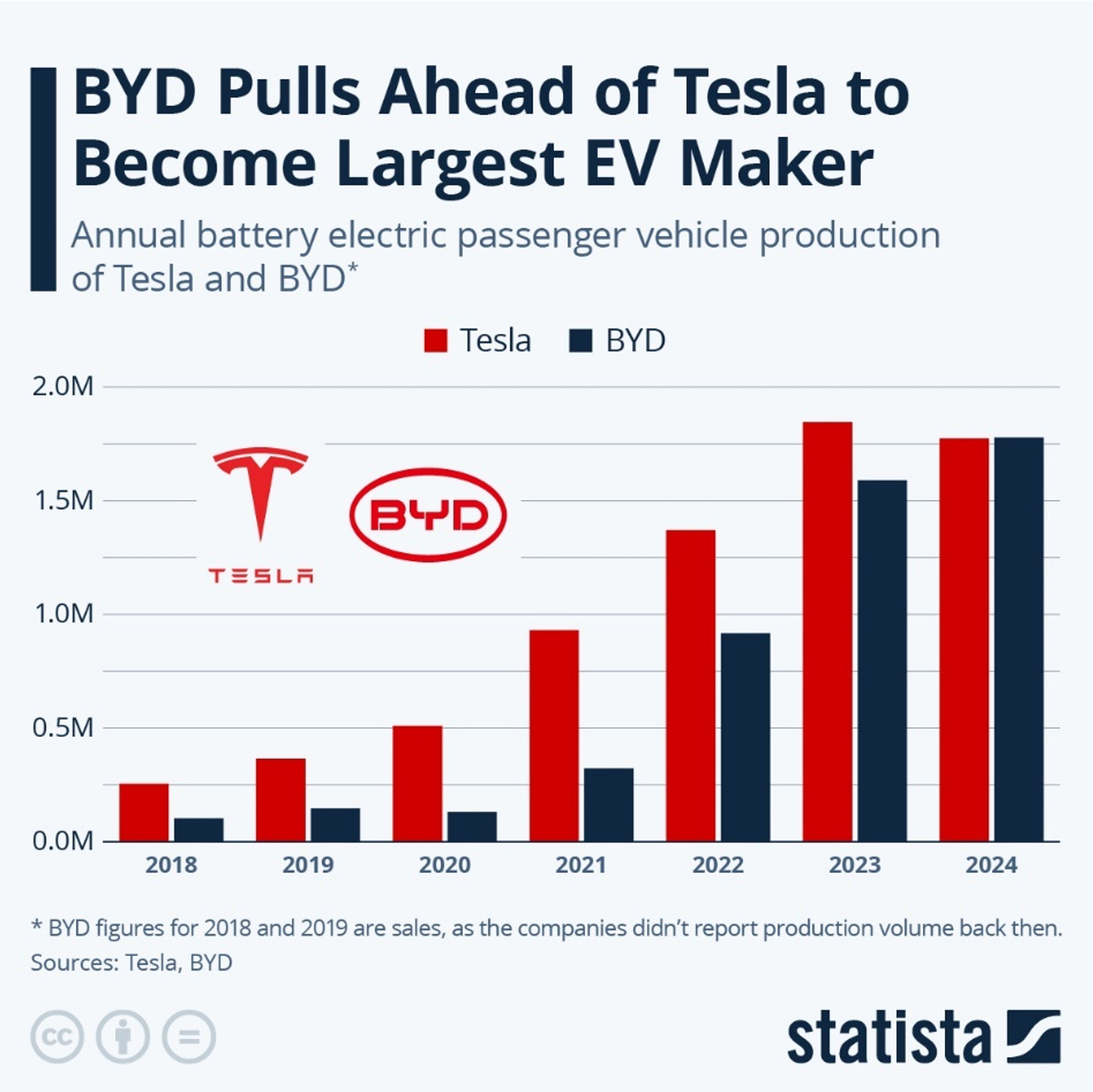

Figure 48: The dynamics of trade deficit countries versus trade surplus countries

A simulation of a 3% government deficit in both countries with a 1% of GDP trade deficit in the USA shows the expected result that the Chinese economy grows more rapidly than the American: the 1% of GDP trade deficit transfers 1/3rd of the money created by the US government deficit to the Chinese economy. Initially, the US economy grows at 4% p.a. while the Chinese economy grows at 8% p.a.. This falls to 6% p.a. as the US economy shrinks relative to the Chinese—see Figure 49. In the absence of a trade imbalance, given the parameters used in this model, both countries would grow at 6% p.a.

Figure 49: A Trade Deficit causes a lower rate of economic growth

All the models and data in this post were created in Ravel.

This is the legitimate basis of the concern the Trump administration has with the USA’s persistent trade deficits. Whether the measures they are taking to address the trade deficit will work is another matter entirely, which I take up in the final section of this chapter. In the meantime, I have to address arguments made by both the Right and the Left of American economics, that trade deficits are actually a good thing.

Arguments that Trade Deficits are Good

There are arguments that trade deficits are in fact good for the deficit country, because they amount to exchanging bank balances for physical goods. Larry Summers, in conversation with Niall Ferguson, put this view succinctly recently:

If China wants to sell us things at really low prices and the transaction is we get solar collectors or we get batteries that we can put in electric cars and we send them pieces of paper that we print. Do you think that's a good deal for us or a bad deal for us?[6]

This argument is also made by advocates of “Modern Monetary Theory” (MMT). Warren Mosler, the originator of MMT, asserted in his free book “Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy”, that in a monetary purchase of an imported commodity, the commodity buyer comes out ahead:[7]

Imports are real benefits and exports are real costs. Trade deficits directly improve our standard of living. Jobs are lost because taxes are too high for a given level of government spending, not because of imports…

In economics, it’s better to receive than to give. Therefore, as taught in 1st year economics classes:

Imports are real benefits. Exports are real costs …

A trade deficit, in fact, increases our real standard of living. How can it be any other way? So, the higher the trade deficit the better. The mainstream economists, politicians, and media all have the trade issue completely backwards. Sad but true…

We have the cars, and they have the bank statement from the Fed showing which account their dollars are in…

We are benefiting IMMENSELY from the trade deficit. The rest of the world has been sending us hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of real goods and services in excess of what we send to them. They get to produce and export, and we get to import and consume. Is this an unsustainable imbalance that we need to fix? Why would we want to end it? As long as they want to send us goods and services without demanding any goods and services in return, why should we not be able to take them?…

Yes, jobs may be lost in one or more industries. But with the right fiscal policy, there will always be sufficient domestic spending power to be able to employ those willing and able to work, producing other goods and services for our private and public consumption. (Mosler 2010, pp. 59-61)

Mosler makes four key assertions here:

That the best way to think about international trade is in terms of barter, rather than in terms of money—this is implicit in the favourable comparison of receiving the commodity to receiving the money from its sale;

That a government deficit is fungible with a trade surplus, so that a country which is running a trade deficit can perfectly offset the effect by running a larger government deficit;

That trade deficits increase the standard of living of the deficit countries, because they are exchanging intangible bank balances for tangible commodities. And, since the sum of all trade deficits is zero, the converse must also apply: that trade surpluses reduce the standard of living of the surplus countries; and

That the USA, as the issuer of the currency used for international trade, benefits from this situation at the expense of the rest of the world.

The first three arguments are false, while the fourth is true for the financial sectors of the US economy, but false for its manufacturing sector.

Barter versus Monetary Analysis

The MMT argument in favour of trade deficits is put in barter terms, and ignores the monetary effects. As shown in the previous section, a monetary analysis shows that a trade surplus benefits the country running it, by increasing money supply growth and enabling a higher level of investment.

The assertion that imports are a benefit and exports are a cost, is based on comparing the usefulness of physical goods to the usefulness of money, and asserting that the former is far greater than the latter:

We have the cars, and they have the bank statement from the Fed showing which account their dollars are in. (Mosler 2010, p. 59)

Firstly, this statement is incomplete. As shown in Figure 47 and Equation , the export surplus country (China) acquires not just the additional US dollar reserves at the Federal Reserve, but also, the additional Chinese fiat money supply generated by the export surplus. This means that a trade surplus can counteract insufficient fiat money creation by the government.

Secondly, this is an inherently static comparison. To toy with the logical foundation of this argument—that “In economics, it’s better to receive than to give. Therefore, … Imports are real benefits. Exports are real costs” (Mosler 2010, p. 59)—I can also assert it is better to relax in a bean bag than it is to go to a gym and work out. But years of doing the former leads to an out of shape body, while doing the latter leads to an in-shape one. It is therefore not the instantaneous comparison of money to goods that matters over time, but the impact of sustained trade deficits and surpluses on the rate of growth, and the product sophistication of economies.

Fungibility of budget deficits and trade surpluses

The fungibility of budget deficits and trade surpluses is true at the aggregate level, in that a dollar created by a government deficit is equivalent to one created by a trade surplus, and that both government deficits and trade surpluses create fiat money. But it is not true when we consider where the created money goes. An export—say the sale of a BYD car in the USA—accrues to the bank account of the firm making the export. Government spending of an equivalent amount of money would be distributed through multiple bank accounts.

The domestic revenues generated by export sales can in turn be used by the exporting company to finance further investment by that company, which can improve its products over time and lead to it enhancing the features, cost or quality advantages which first enabled that company to sell its products in place of domestically produced ones.

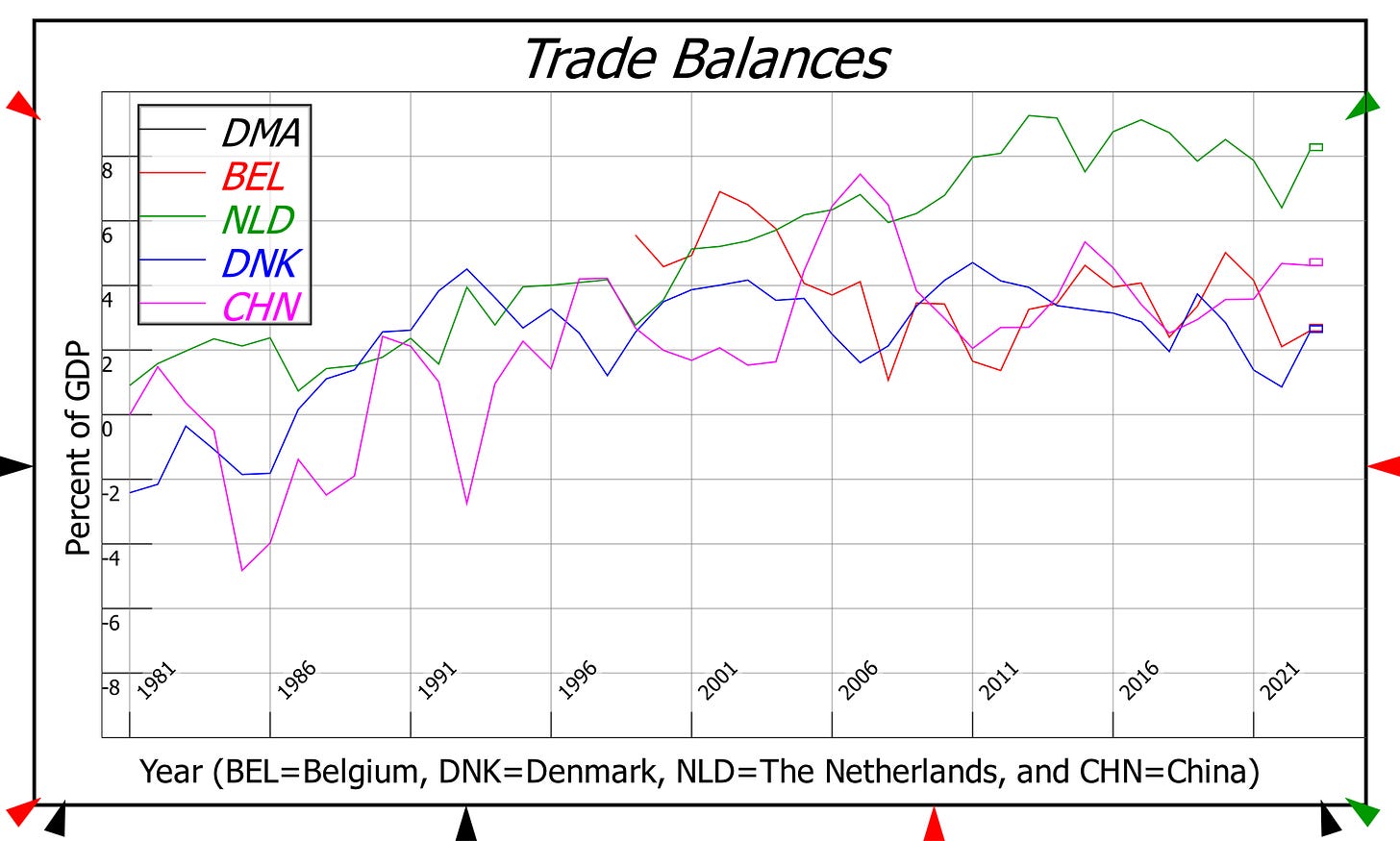

This was the method that Japanese auto makers used in the 1960s to expand their market share in the USA, and many other countries. Chinese companies like BYD are doing the same thing now. In 2013, Musk ridiculed BYD cars, and stated that he did not see them as a competitor—see the interview linked in Figure 50.

Figure 50: Musk reacts to BYD being seen as a competitor in 2013

Since then, BYD has improved its quality, and expanded its range and sales dramatically. As of 2024, BYD surpassed Tesla’s global sales volume—see Figure 51. I expect that Musk sees BYD as a competitor today.

Figure 51: Statista's chart showing BYD sales volume exceeding Tesla's in 2024 https://www.statista.com/chart/33709/tesla-byd-electric-vehicle-production/

This specific example supports the basic point that sales revenue from exports enables exporting companies to invest more than they could invest with domestic revenues alone. A country in which these firms dominate importing companies so that a trade surplus is generated is more likely to improve its productive capabilities and grow more rapidly than a country where the converse applies.[8] The same stimulus to innovation is not likely to come from an equivalent government deficit.

Trade Surpluses and the Standard of Living

More realistically, export surpluses by firms can compensate for the fact that most countries do not in fact run “the right fiscal policy”, but routinely run budget deficits that are too small, because they are run by politicians and bureaucrats who accept the false Neoclassical view that the government should ideally run a balanced budget. Firms that generate substantial export revenues can avoid the consequences of that policy mistake. If a country, such as The Netherlands, runs a sustained large trade surplus, this can counteract the damaging impact of policy constraints on budget deficits, such as those imposed by the Maastricht Treaty—see Figure 52.

Figure 52: Some countries whose budget deficits are policy constrained compensate by running trade surpluses

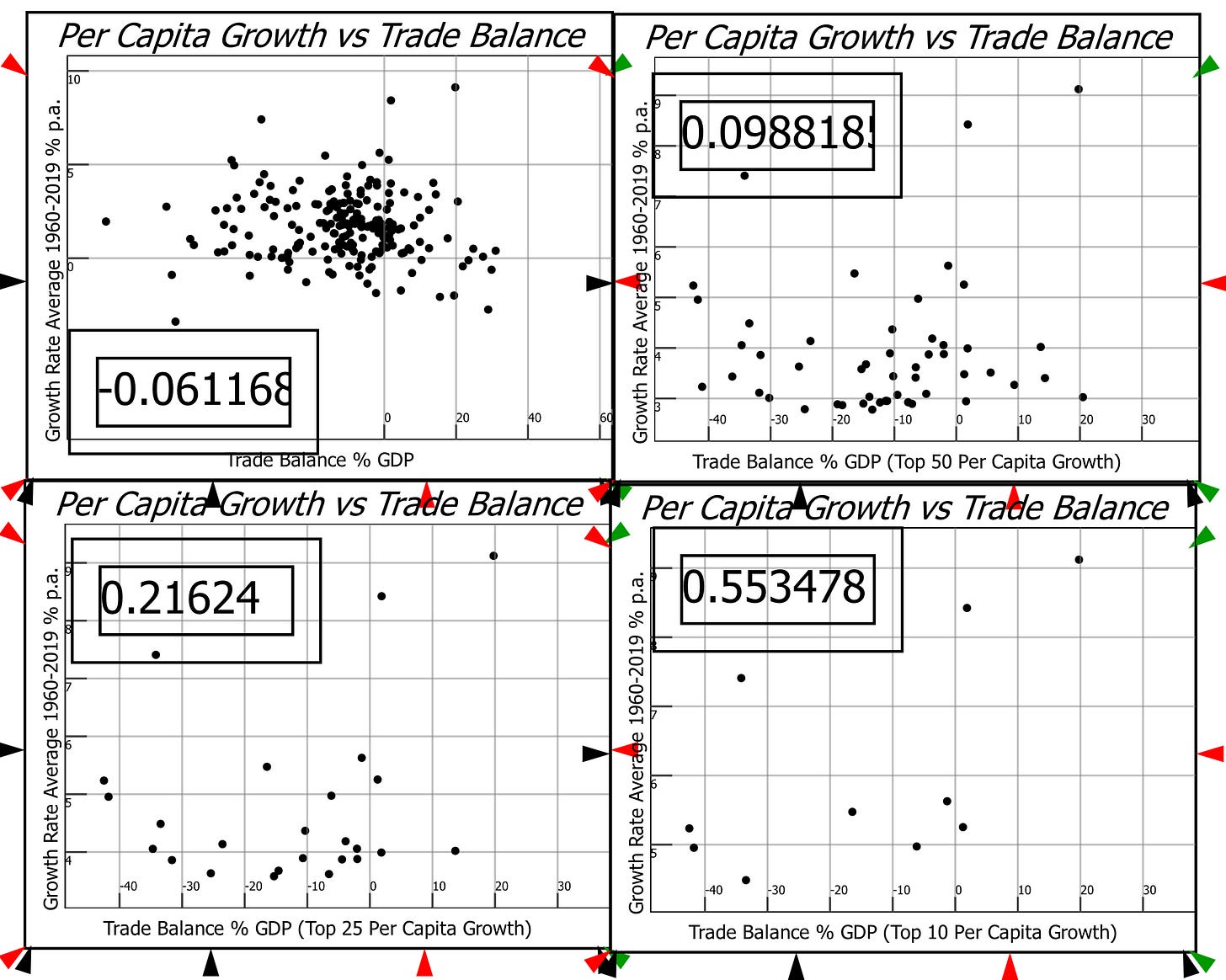

The economic growth and trade surplus data is equivocal at the global level. As the top left plot in Figure 53 shows, there is a very weak negative relationship between trade balances and per capita growth rates for all countries in the data.[9] However, as we drill down into the top countries by per capita growth performance over the period from 1980 till 2019, a relationship emerges: for the top per capita growth rate performers, the relationship between trade surpluses and per capita economic growth is positive, not negative as the “Imports are real benefits. Exports are real costs” argument implies.

Figure 53: A trade surplus is associated with a higher rate of economic growth.

China is of course the most dramatic example of a country which has industrialised and run sustained trade surpluses. China had negative trade balances early in its post-Mao industrialisation days, peaking at 4.9% of its GDP in 1985, but its trend has been towards larger surpluses over time.

China has also dramatically out-performed the US economy over the last 40 years. The gap in performance is astounding. China, which has run an average trade surplus of 2.1% of its GDP, has grown per capita income at an average of 8.1% per year. The USA, which has run an average trade deficit of 3.7% over the same period, has had per capita income growth of just 1.7% p.a.

If the “exports are a cost, imports are a benefit” mantra were true, and the USA was benefiting from goods that China could have used for itself, then there would need to be other truly outstanding differences between the two countries to explain why it is that, despite this advantage, the USA has performed so poorly.

Figure 54: USA vs China Growth and Trade Balance

A major factor in China’s rise has been the increase in the complexity of products it is capable of producing. In 1995, China ranked 38th in Harvard University’s Atlas of Economic Complexity,[10] while the USA ranked 10th. By 2023, China had risen to 15th in the world, while the USA had fallen to 14th. It has moved up the complexity ladder in part because of its substantial trade surplus, which have added to the growth of the domestic money caused by China’s sustained budget deficits, and enabled a higher level of investment than would have been possible otherwise.

Figure 55: USA has lost and China has gained in Complexity Rankings https://atlas.hks.harvard.edu/rankings

The US’s Exorbitant Privilege

The one point in MMT’s list of favourable impacts of a trade deficit which is true is that the current system, with the US dollar being used for international trade, is that it gives the US a privilege which no other country enjoys. If any other country runs a balance of payments deficit, then it has to acquire US dollars by either borrowing in US dollars—and thus acquiring the liability of having to make export sales simply to finance interest payments on that debt—or by selling domestic assets.

The US, on the other hand, can simply create US dollars, either by running a government deficit, or by private sector borrowing from private banks. Mosler provides a trader’s perspective on this situation when he says that:

We are benefiting IMMENSELY from the trade deficit. The rest of the world has been sending us hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of real goods and services in excess of what we send to them. They get to produce and export, and we get to import and consume. Is this an unsustainable imbalance that we need to fix? Why would we want to end it? As long as they want to send us goods and services without demanding any goods and services in return, why should we not be able to take them?… (Mosler 2010, p. 61)

This is arguably true for the United States, but it cannot be true for the World as a whole, because the sum of all trade balances is zero. Therefore, if the MMT argument that trade deficits are good were true, MMT should also support policies which minimise trade deficits globally. They have not.

In contrast, someone who argued the opposite case to MMT—that countries running trade surpluses benefit at the expense of those running deficits—has proposed such a scheme. That someone is John Maynard Keynes, and I outline his scheme in the final section of this chapter.

Profits rise with rising sales volume

An important additional reason why trade surpluses are beneficial to the countries running them is how firms cost’s change with rising output, as discussed in in the “A Realistic Pricing Equation” of Chapter 8 on page 64.

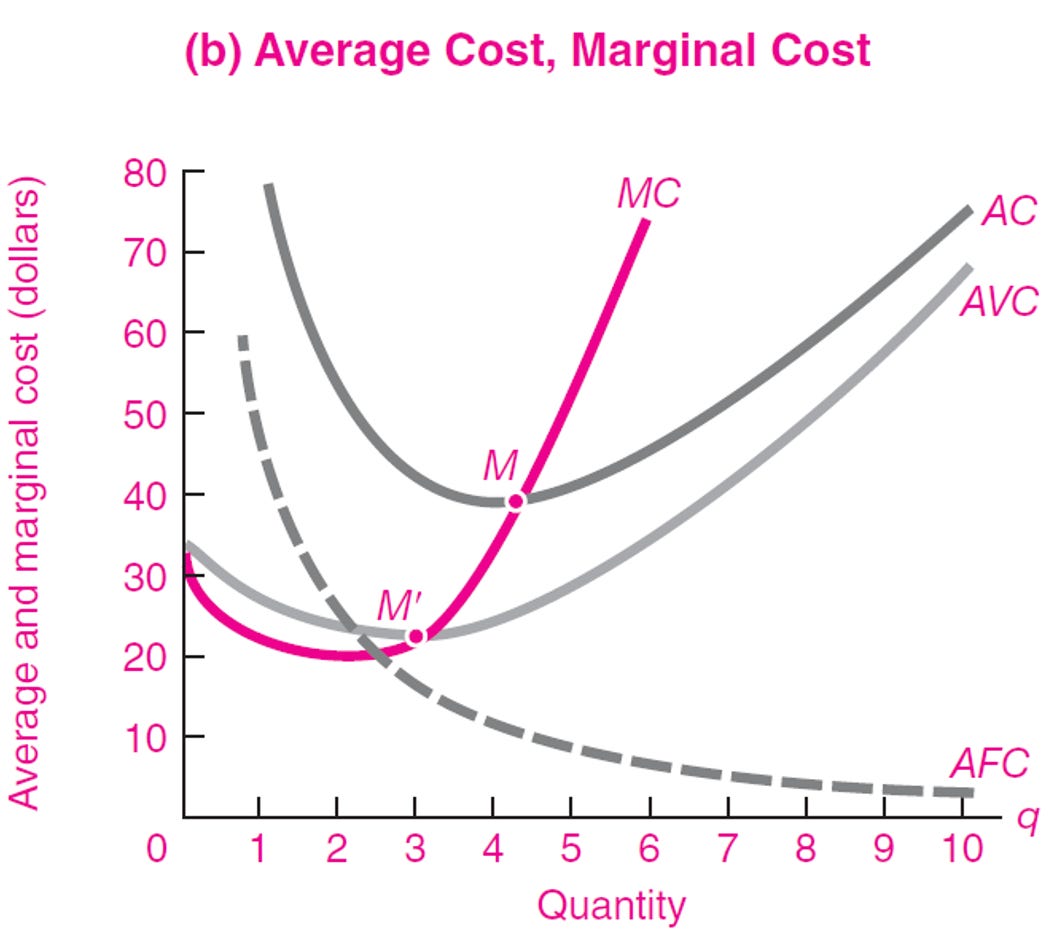

Neoclassical theory teaches that firms produce homogeneous products under conditions of diminishing marginal productivity, which causes marginal cost to rise as output rises, and it assumes that average fixed costs are a trivial component of total costs—see Figure 56, which reproduces the relevant drawing from the Samuelson and Nordhaus Economics textbook. Such mythical firms cannot benefit from increasing sales volume, if they are already at the point at which profit is maximized by equating marginal cost and marginal revenue.

Figure 56: The fallacious Neoclassical model of firm cost curves. Figure 7.2 from (Samuelson and Nordhaus 2010b, p. 131)

This model, implicitly or otherwise, lies behind the arguments that China does not benefit from the increased output levels that exports enable. Why would you increase output if you were already at the point of maximum profit from domestic demand alone?

However, in the real world, as explained in Chapter 8 (in the section “A Realistic Pricing Equation”, page 64 et. seq.), firms sell differentiated product into segmented markets, and they have constant or falling marginal costs, and extremely large per unit fixed costs, as shown in Figure 57 (which reproduces Figure 38). For growth and competitive reasons, firms operate with significant excess capacity in their domestic markets,[11] and competition involves taking market share away from known rivals. This is done by amortizing fixed costs over a larger volume of output. As sales rise, the markup on variable per unit costs remains relatively constant, but the markup on total costs rise because of falling per unit fixed costs.

Figure 57: The actual cost structure of the typical firm in a differentiated product market

Real-world firms, unlike their fictional counterparts in economic textbooks, therefore profit by selling as many units as possible. If they can secure export sales in addition to domestic sales, their per-unit cost of production falls, and profit margins rise. This phenomenon was detailed in a recent IEA report on car battery technology,[12] which the YouTube technology commentator @JustHaveaThink noted showed that:

For many of them, even after shipping costs and swingeing tariffs by the European Union, and the USA, selling into those territories represents an opportunity to undercut the well-established Western automotive brands and still achieve higher profits than they get back home.

Figure 58: "Have batteries just hit their exponential curve??"

Some defenders of trade deficits argue in terms of opportunity cost. They assert that the exporting country loses out of trade, because it loses a physical product which it could employ in its own economy, while all it gets in exchange for its physical product is an increase in its holdings of a foreign currency:

For an economy as a whole, imports represent a real benefit while exports are a real cost. Exports mean that we have to give something real to foreigners that we could use ourselves – that is obviously an opportunity cost. Imports represent foreigners giving us something real that they could use themselves but which we benefit from having. The opportunity cost is all theirs! (Bill Mitchell, “There is no internal MMT rift on trade or development”, https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=41327)

However, there is no “opportunity cost” involved in exporting a manufactured good, because if the export did not occur, the good would simply not be produced and sold in the first place. And yet this Neoclassical concept—which, even in Neoclassical theory, applies only when all resources are fully employed—is being used by non-Neoclassical economists to defend the argument that “exports are a cost and imports are a benefit”.

It is also entirely a barter-based argument.[13] This, again, is understandable when espoused by Neoclassical economists like Larry Summers , but it is jarring when it comes from proponents of MMT, which provides a strictly monetary analysis of government spending.

When analysed from the same monetary perspective as MMT analyses government deficits, the two concepts of MMT—that “the funds to pay taxes, from inception, come from government spending” (Mosler 2010, p. 20) and “Imports are real benefits and exports are real costs. Trade deficits directly improve our standard of living” (Mosler 2010, p. 59)—are in conflict. In fact, the only thing that the two foundation concepts of MMT undeniably have in common is that they were originally made by the same person. Mosler got government money creation right, but got international trade wrong because he has ignored the money creation effects of trade imbalances.

A Better Way to Limit Trade Imbalances

Someone else who argued that trade imbalances benefit the net exporting country, by enabling a higher rate of investment than in the importing country, is a name that is not normally associated with Donald Trump: John Maynard Keynes.

Like Miran today, Keynes realized that being the international reserve currency was not a perk of Empire, but a spoiler, and for the same reasons: the Empire had to run a trade deficit to supply the currency needed by other nations, and the demand for its currency over and above that needed to buy its goods put its domestic industries at a disadvantage to other countries. The UK’s share of global manufacturing exports fell when the British Pound was the international currency, and the USA’s share has plunged precipitously during its tenure as the international currency —see Table 12.

Table 12:The United Kingdom's Share of World Exports of Manufactures Compared With Six Other Industrial Countries, 1881–1973 (Matthews, Feinstein, and Odling-Smee 1982, Table 14.5)

(Percent, based on values in U.S. $ at current prices)

Also like Miran today, Keynes argued that export surplus countries benefited from that surplus in terms of investment and growth levels. Like Miran, and unlike Summers and Mosler, Keynes saw export surplus countries as being the winners from trade imbalances. But he came up with a scheme to limit both surpluses and deficits, and which could have financed Third World development at the same time.

He proposed at the Bretton-Woods meeting in 1944, but he was defeated by the most influential member of the American delegation, Harry Dexter White.[14]

We all know White’s scheme: use the US$ for international trade, and guarantee convertibility of the dollar into gold at US$35 an ounce. That jalopy crashed in 1971, when the one of the many fundamental problems with its design—persistent US trade deficits and persistent surpluses for other countries—forced the breaking of the “Gold Standard”.

We’re living in the wreckage of the jalopy’s second crash, after more than four decades of floating exchange rates have not delivered the balanced trade that the advocates of free trade and floating exchange rates promised.

The Trump Administration is currently trying to right the fundamental problem—persistent trade deficits for the USA and persistent surpluses for other countries—by patching White’s jalopy up once again. A better way would be to rebrand Keynes’s proposal to limit trade imbalances as its own. In my explanation below, I’ll use the name that Keynes suggested for his international exchange token, the “Bancor”. But it could just as easily be called the Trump.

The International Clearing Union and the Bancor

In place of using a national currency for international trade, Keynes proposed a token he called the Bancor, which would be transacted through national accounts at an “International Clearing Union” (ICU).

Keynes’s idea was not to create a new currency, but to replicate the fundamental structure of national banking at the international level:

The idea underlying my proposals for a Currency Union is simple, namely to generalise the essential principle of banking, as it is exhibited within any closed system, through the establishment of an International Clearing Bank.

This principle is the necessary equality of credits and debits, of assets and liabilities. If no credits can be removed outside the banking system but only transferred within it, the Bank itself can never be in difficulties.[15] (Keynes 1941, p. 2)

Therefore, the Bancor was not a currency as such, but a unit of account. Countries running trade surpluses would run up positive balances at the ICU, while deficit countries would run up negative balances, with the total summing to zero. Keynes called countries with persistent trade deficits “Debtor Countries” and those with persistent surpluses “Creditor Countries”. The novel aspect of Keynes’s plan was that it put “at least as much pressure of adjustment on the creditor country, as on the debtor.” The overriding objective was to create a mechanism to balance trade at the global level:

Countries having a favourable balance of payments with the rest of the world as a whole would find themselves in possession of a credit account with the Clearing Union, and those having an unfavourable balance would have a debit account. Measures would be necessary to prevent the piling up of credit and debit balances without limit, and the system would have failed in the long run if it did not possess sufficient capacity for self-equilibrium to secure this. (Keynes 1943, p. 367. Emphasis added)

Though no actual Bancor were created, countries would be given quotas based on the sum of their exports and imports (Keynes initially proposed that the quota would be equal to half that sum, then he suggested 75%).[16] When a country’s outstanding balance exceeded a target fraction of this quota, the country would be required to revalue its currency in terms of Bancor—increasing its value if it was a Creditor Country to make its exports more expensive, reducing its value if a Debtor Country to make its exports cheaper.

In addition, Keynes proposed interest charges on Debit and Credit Balances:

A member State shall pay to the Reserve Fund of the Clearing Union a charge of 1 per cent. per annum on the amount of its average balance in bancor, whether it is a credit or a debit balance, in excess of a quarter of its quota; and a further charge of 1 per cent. on its average balance, whether credit or debit, in excess of a half of its quota. Thus, only a country which keeps as nearly as possible in a state of international balance on the average of the year will escape this contribution. (Keynes 1943, p. 369)

Policies like Germany’s recent practice of suppressing wage rises to maintain an export surplus would be replaced by policies to stimulate export surplus economies and generate more demand for imports:

A member State whose credit balance has exceeded a half of its quota on the average of at least a year shall …[take] measures … appropriate to restore the equilibrium of its international balances, including—(a) Measures for the expansion of domestic credit and domestic demand. (b) The appreciation of its local currency in terms of Bancor, or, alternatively, the encouragement of an increase in money rates of earnings; (c) The reduction of tariffs and other discouragements against imports. (d) International development loans. (Keynes 1943, p. 371)

Finally, Keynes’s scheme would have prevented the development of tax havens and offshore banking which has been an endemic feature of the system that White bequeathed us at Bretton-Woods:

There is no country which can, in future, safely allow the flight of funds for political reasons or to evade domestic taxation or in anticipation of the owner turning refugee. Equally, there is no country that can safely receive fugitive funds, which constitute an unwanted import of capital, yet cannot safely be used for fixed investment. For these reasons it is widely held that control of capital movements, both inward and outward, should be a permanent feature of the post-war system. (Keynes 1943, p. 381)

Figure 59 shows the basic operations that the ICU would undertake, including funding international development by interest charges on surplus and deficit nations.

Figure 60 shows the impact of these operations on a Deficit Country. A key aspect here is that a trade deficit is, at least to some extent, offset by purchases from developing countries, which would be funded by the interest charges that are levied on both surplus and deficit countries. This is an “automatic stabilizer” feature of Keynes’s proposal, in strong contrast to the existing system that has enabled surplus countries to turbocharge their growth at the expense of deficit countries—most notably the USA—for decades.

Figure 60: The implications of a trade deficit via the ICU

This scheme, and not a blanket system of “reciprocal tariffs” by all nations against all other nations, is the right way to reduce the trade imbalances that have crippled America’s manufacturing. If Trump really wants to be remembered forever, then the way to do that would be to introduce Keynes’s scheme, and to rebrand it as his own.

The day on which Trump introduces a system that could virtually eliminate trade imbalances forever more would truly be a day to remember. We could even drop Keynes’s proposed name of the Bancor, and call the unit of account the Trump.

Technical Appendix

Figure 61 shows the simulation model used in this chapter in Ravel.

The differential equations in this model are shown in Equation :

Equation shows the variable definitions in this model:

[1] See

.

[2] See https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/04/cea-chairman-steve-miran-hudson-institute-event-remarks/.

[3] See https://www.hudsonbaycapital.com/documents/FG/hudsonbay/research/638199_A_Users_Guide_to_Restructuring_the_Global_Trading_System.pdf.

[4] See https://www.investopedia.com/insights/what-is-the-balance-of-payments/.

[5] For simplicity of exposition, I assume that firms export and households import, while governments spend on firms and tax households.

[6] See

.

[7] This book is free to download from http://moslereconomics.com/wp-content/powerpoints/7DIF.pdf.

[8] This is not to denigrate the importance of imports per se—some imports are driven by the need to acquire inputs to production which do not exist in the importing country—but rather the argument that imports in the aggregate are a benefit and exports in the aggregate are a cost.

[9] Trade data is from https://stats.wto.org/; per capita growth data comes from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD.ZG.

[10] See https://atlas.hks.harvard.edu/.

[11] Capacity utilization in the USA has fallen from 90% in the 1970s to 75% now, and it is highly cyclical (see https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TCU). Chinese capacity utilisation has averaged 75% since data collection began in the early 2000s, is also highly cyclical, and has no trend (see https://data.stats.gov.cn/english/easyquery.htm?cn=B01).

[12] See IEA (2025), The battery industry has entered a new phase, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-battery-industry-has-entered-a-new-phase.

[13] On this front, I recommend reading Richard Murphy’s critique of Mitchell’s assertions: “Why Bill Mitchell is simply wrong on modern monetary theory and imports and exports” (https://shorturl.at/42dd2). I wrote a blog post with a similar argument in 2018:”MMT’s ignorance of economic thought” (https://shorturl.at/ExXPm).

[14] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Dexter_White.

[15] See https://la.utexas.edu/users/hcleaver/368/368keynesoncutable.pdf.

[16] This requires measuring the monetary value of international trade, which would initially have to be done in a national currency—say the UK£ or US$. Were we to replicate Keynes’s scheme today, then the relative value of national currencies to the Bancor would be set to match current market exchange rates at the time of commencement of the ICU.

Steve

Great stuff and I look forward to your book…

I am the author of Take Back Manufacturing, and my Substack talks to that.

In principle I agree with what Trump is trying to do but am somewhat dismayed with his process and approach.

I believe we have globalized our trade and financialization processes far too much and must go back to trade blocs and nations grouped into economic unions such as the whole of North America for example. We must lock out all trade and financial transactions outside of this bloc and focus on keeping all value inside the bloc.

I therefore don’t believe another multilateral global trading token like the Bancor is the way to go as we have far too large a wealth gradient between the west and the rest for any significant trade to make sense unless they are essential materials that cannot be mined or grown inside the bloc. All value adding effort must stay inside the bloc. It’s the only way to maximise the economy inside the bloc.

It needs to be agreed that trade outside the bloc is to be abhorred as trading is not a god given right to expect from another and its only an option if it benefits the recipient and its clear that it has not done that for the west in the past as its bred labor arbitrage driven by the freedom of national capital placed in the hands of corporations that went transnational.

Your math which I am not an expert at does reinforce that situation... and its clear that we need to bury the free market thinking most of economists used to screw us up and rebalance the capital and labor in each nation as its clear that as long as people need to work to live and try to build capital to stop working they need a better balance and that is what trump is doing.. I just wish he followed a better implementation process that does not confuse the heck out of everyone.

Let me know what you think of my position.