In the last post (Substack; Patreon), I showed how private banks create money, by marking up their Assets (Loans to the Private Sector) and their Liabilities (Deposits of the Private Sector) simultaneously. I also pointed out that in a pure private sector economy, since banks must be in positive financial equity, the private non-bank sector is necessarily in negative financial equity: in the aggregate, the private non-banking sector will have financial liabilities that exceed its financial assets.

This isn’t an impossible situation: firms and households can service their debts, so long as the money they’ve borrowed into existence is used to create and sell goods and services that enable them to pay the interest on their debts. But it’s an uncomfortable situation: no-one likes having negative net financial worth.

Is there a solution? Let’s look at the double-entry bookkeeping.

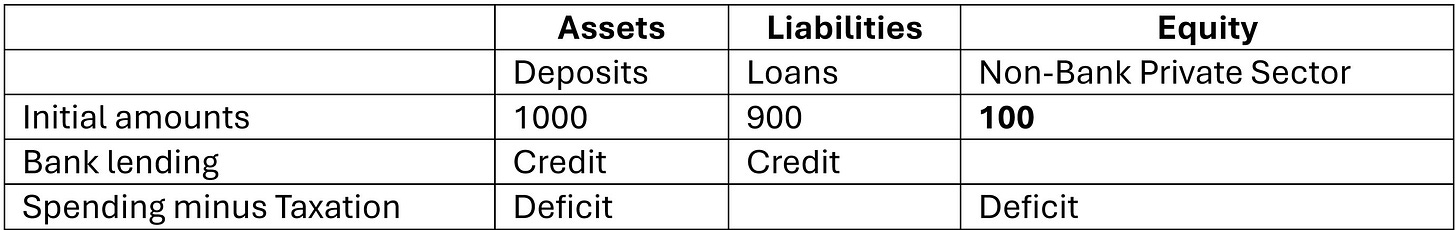

If government spending exceeds taxation, we call the difference a Deficit. As I explained in the second post (Substack; Patreon): a Deficit increases the bank deposits of the private sector, so it adds to the money supply, just as new Credit money does.

What it does differently is it doesn’t increase Loans on the Asset side of the banking sector’s ledger—which is what private bank lending does—but instead, it increases what are normally called Reserves (these are better described as “Settlement Accounts”, but I’ll stick with the Reserves name for now). This is shown in the final line in Table 1.

Table 1: Bank Lending and a Government Deficit from the banking sector's point of view

Table 2 shows the non-bank private sector’s perspective, and there are two essential differences between this system and the private-sector-only one shown in the second post (Substack; Patreon):

· The non-bank private-sector’s financial equity is now a positive $100 billion, rather than the negative $100 billion of the private-banking-only system; and

· Unlike a loan from a bank, the government deficit adds to the non-bank private sector’s net worth.

This is obvious from the double-entry table for the non-bank private sector, as shown in Table 2. Its Assets—Bank Deposits—have risen by Deficit dollars per year; there is no offsetting Liability for the Deficit—unlike the situation for a bank loan; therefore, the Deficit has increased the net worth of the private sector.

Table 2: Bank Lending and a Government Deficit from the non-bank private sector's point of view

This is the exact opposite of what mainstream economists claim. Citing a first-year economics textbook—which is where most politicians and journalists learn what they think is sound economics—mainstream economics claims that a government deficit reduces national saving:

the government finances the additional spending … by reducing public saving. With private saving unchanged, this government borrowing reduces national saving. (Mankiw 2016, p. 73)

Remarkably, this statement is half-right: it is true that a government deficit reduces public saving—as I’ll show in the next post. But Mankiw’s statement that private sector saving is unchanged by the deficit is false: the deficit increases private saving.

He—and all other mainstream economists—get this wrong because they don’t check the double-entry bookkeeping, but instead draw silly supply and demand diagrams, and move the lines around the wrong way. In the next post in this series, I’ll show the government’s eye view of a deficit, using the only tool that makes sense of money creation: double-entry bookkeeping.

Free subscribers: if Substack’s $5 a month is too much, consider supporting me via Patreon for as little as $1/month or $10/year: https://www.patreon.com/ProfSteveKeen.