Ted Cruz has claimed that the Federal Reserve should stop paying banks interest on Reserves:

The Federal Reserve pays banks interest on reserves. For most of the history of The Fed, they never did that. But for a little over a decade, they have. Just eliminating that saves $1 trillion. (YouTube video embedded below)

Figure 1: Cruz interviewed on CNBC

With a few caveats, Cruz is right. And the story of how The Fed got itself into this situation is a tale of gross incompetence.

The Fed had no idea that a crisis was approaching in the years leading up to the Global Financial Crisis. Instead, in common with the economics profession in general, it thought that the economy was on its way towards Heaven on Earth.

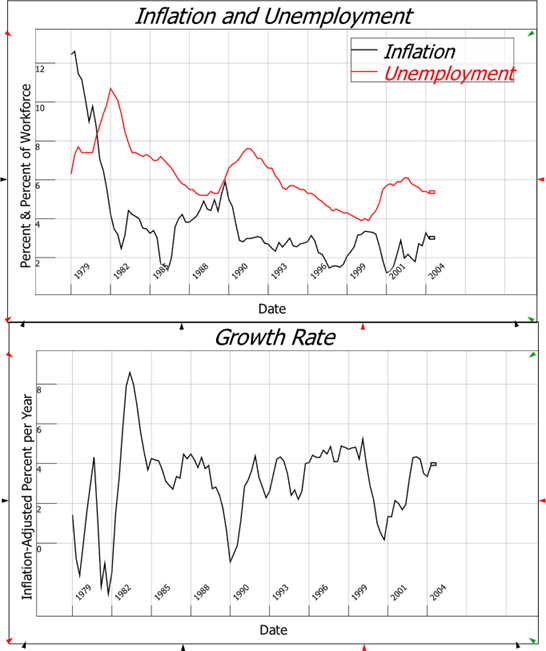

Over the previous three business cycles, the peak level of inflation had fallen during the booms, the peak level of unemployment had fallen during the slumps, and recessions had become shallower: the minus 2.5% real rate of growth of 1982 was followed by minus 1% in 1990, and a plus 0.1% bottom to the 2001 recession—see Figure 2.

Mainstream “Neoclassical” economists were so enamored of this phenomenon that they christened it “The Great Moderation” (Campbell 2007; Summers 2005; Bernanke 2004a).

Figure 2: The Great Moderation

In October 2004, Bernanke attributed this superficially excellent result to The Fed’s focus on fighting inflation first, and letting the unemployment rate take care of itself:

the low-inflation era of the past two decades has seen not only significant improvements in economic growth and productivity but also a marked reduction in economic volatility … a phenomenon that has been dubbed "the Great Moderation"… improved control of inflation has contributed in important measure to this welcome change in the economy. (Bernanke 2004b, p. 1)

At the other end of the planet, and a decade earlier, I warned that falling volatility was actually an indicator that a crisis was imminent. An unexpected outcome of my model of the maverick economist Hyman Minsky’s “Financial Instability Hypothesis” was that volatility declined just before a crisis, as cycles gave way to a collapse driven by rising private debt and falling prices—a “Debt-Deflation”, as Irving Fisher called it (Fisher 1933)—see Figure 3.

Figure 3: In my model of Minsky's Financial Instability Hypothesis, the crisis is preceded by a "Great Moderation"

At the time I wrote these words, in August of 1992, I had no idea how prophetic they would prove to be:

this vision of a capitalist economy with finance requires us to go beyond that habit of mind that Keynes described so well, the excessive reliance on the (stable) recent past as a guide to the future. The chaotic dynamics explored in this paper should warn us against accepting a period of relative tranquility in a capitalist economy as anything other than a lull before the storm. (Keen 1995, p. 634)

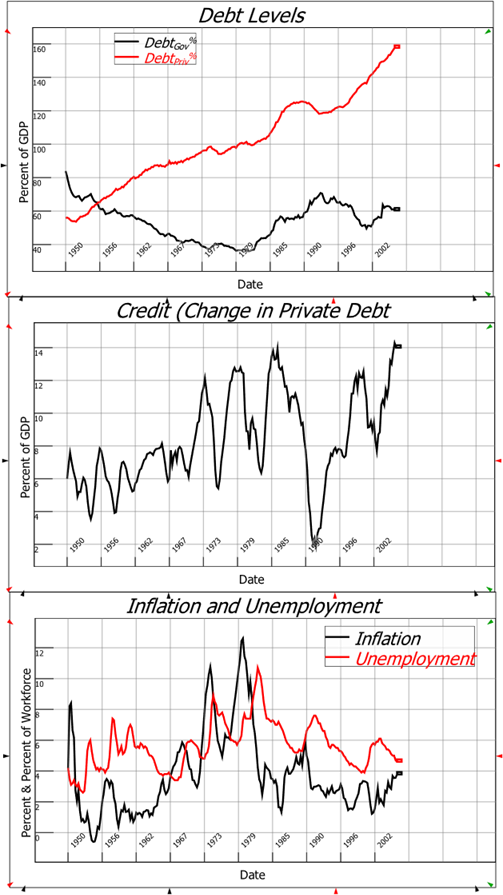

A decade later, a legal case in which I was an expert witness led me to check the Australian and US data closely, and everything that my model said would lead to chaos was in place. Rising private debt, credit (the annual change in private debt) getting larger relative to GDP, and declining cycles in inflation and unemployment—which Bernanke saw as a good thing—all implied to me that a crisis was inevitable in the near future.

Figure 4: The indicators that led me to anticipate the Global Financial Crisis

In May 2007, I wrote that “At some point, the [private] debt to GDP ratio must stabilise--and on past trends, it won't stop simply at stabilising. When that inevitable reversal of the unsustainable occurs, we will have a recession” (Keen 2007).

In contrast, in his Report to the Congress as Fed Chairman in July 2007, Bernanke brimmed with confidence as he asserted that the immediate economic future was very bright indeed.

Figure 5: The cover of Bernanke's Report to the Congress as Chair of the Federal Reserve

The economy was in good shape, he opined, and it was going to improve even more in the coming years:

Financial market conditions have continued to be generally supportive of economic expansion thus far in 2007… The U.S. economy seems likely to continue to expand at a moderate pace in the second half of 2007 and in 2008…

The members of the Federal Reserve Open Monetary Committee (FOMC)—the body which sets interest rates, and monetary policy in general—were confident that growth would not only continue, but it would accelerate:

The central tendency of the FOMC participants’ forecasts for the increase in real GDP is 2¼ percent to 2½ percent over the four quarters of 2007 and 2½ percent to 2¾ percent in 2008… Economic activity appears poised to expand at a moderate rate in the second half of 2007, and it should strengthen gradually into 2008. (Bernanke 2007)

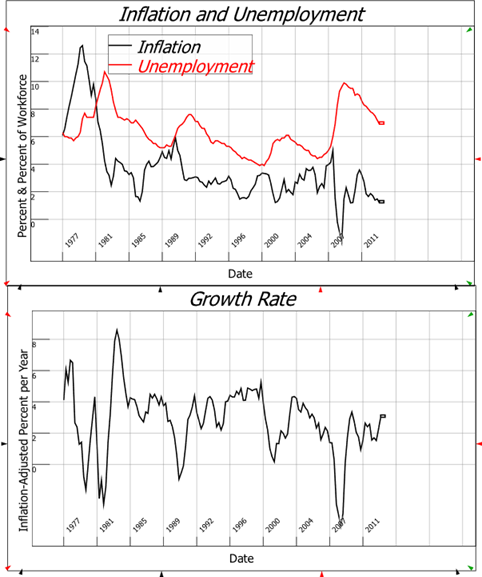

Just one month later, the “Global Financial Crisis”—also known as the “Great Recession”—began. The trend of declining unemployment and inflation gave way to rapidly rising unemployment, a short-lived burst of deflation, and real economic growth plunging to minus 4 percent, far deeper than the previous three recessions—see Figure 6.

Figure 6: The "Great Moderation" gave way to the "Great Recession" in late 2007

Having expected good economic times rather than a crisis, The Fed was at a loss about what to do. So it borrowed an idea from Japan, which had been through a similar crisis two decades earlier: “Quantitative Easing”. This involved The Fed buying bonds off the private financial sector.

This had the intended side-effect of dramatically increasing the level of Reserves.

Before the Global Financial Crisis, Reserves were so low as to be virtually zero—between 1960 and 2007, Reserves never exceeded $100 billion in the USA’s multi-trillion dollar economy: see Figure 7. It didn’t matter to banks that they didn’t receive interest on Reserves, because the amount of money involved was trivial. The real money-making deal for the banks was buying bonds from the Treasury, using those Reserve funds.

Figure 7: The Fed dramatically increased Reserves when the GFC hit. See https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TOTRESNS#

The reason why Reserves were so low for so long is easy to understand, using my modelling software Ravel: see Figure 8.

Figure 8: The accounting operations involved in government deficit spending, bond auctions, and QE

When the government runs a deficit—when it spends more than it takes back in taxation—it increases the amount of money in Deposit accounts. It does this by putting funds into the deposit accounts of private banks at The Fed—which is what “Reserves” actually are. These are the first two rows in Figure 8.

Then the Treasury sells bonds equivalent to the deficit plus interest on existing bonds, in what is known as a “Primary Bond Auction”. These are purchased using the Reserves that were created by the deficit. Banks always buy these bonds, because it lets them swap a non-interest-earning, non-tradeable asset, for an income-earning, tradeable asset. Reserves fall and bank bond holdings rise: this is the 3rd row. The banks then receive interest income from the bonds—the 4th row.

But QE reverses this. The Fed buys bonds off the banks, and Reserves rise as a result. This is the 5th row.

This process flooded the system with Reserves: Reserves went from $65 billion in July 2008 to a trillion dollars in October 2009, and they ultimately hit 4 trillion dollars after Covid (see Figure 7). With that much in Reserves, and that much less in Bonds, the income banks received from the government plunged. Suddenly it mattered that Reserves earnt no interest, and the Federal Reserve accommodated the banks by introducing interest payments on Reserves in July of 2008—see Figure 9.

Figure 9: Interest rate on Reserves

This move meant that it didn’t really matter to the banks whether they held their government-created assets in the form of Treasury Bonds or Reserves: they received almost the same amount of interest from Reserves as they did from Bonds.

Why did The Fed think that it was a good idea to increase the level of Reserves? Because in the textbook model that all mainstream economists believe, banks lend out Reserves to the private sector via what the textbooks call “the Money Multiplier”. A bank, the textbooks tell us, hangs on to 10% of the money deposited with it as Reserves, and lends out the rest. The borrowers then deposit that money at another bank, and the process repeats. That way, a $1 billion increase in Reserves could translate into $10 billion in new loans, which would stimulate economic activity.

Obama’s economic advisors sold him this pup, and he duly repeated it, in classic Obamaese, in his first major speech as President in April 2009:

And although there are a lot of Americans who understandably think that government money would be better spent going directly to families and businesses instead of banks – "where's our bailout?," they ask – the truth is that a dollar of capital in a bank can actually result in eight or ten dollars of loans to families and businesses, a multiplier effect that can ultimately lead to a faster pace of economic growth. (Obama 2009. Emphasis added)

Some members of the FOMC fretted that this could lead to an explosive increase in the money supply, which would cause a burst of inflation:

Banks have $1 trillion of excess reserves. These reserves represent an inflation risk generated from potential changes in household expectations (FOMC 2009, Mr. Kocherlakota, p. 111)

as economic growth picks up and becomes more sustainable … The money multiplier will go up, and those excess reserves will flow rapidly out into the economy… (FOMC 2009, Mr Plosser, p. 108)

Others worried that the policy would fail, because banks would decide not to lend out these funds:

I think that the verdict on quantitative easing is fairly negative. It didn’t seem to have a great deal of effect, mostly because banks would not lend out the reserves that they were holding. (FOMC 2009, Chairman Bernanke, p. 25)

I just don’t see any evidence that the base isn’t going to be absorbed in a declining money multiplier rather than an expanding money supply and increased activity. (FOMC 2009, Mr. Kohn, p. 69)

The FOMC members who worried that boosting reserves wouldn’t lead to more economic growth and inflation were right, but for the wrong reasons. They thought that banks would decide not to lend out the reserves, but the truth is more ridiculous: banks can’t lend out reserves, unless all loans are in cash.

This is also easily illustrated by Ravel. Banks operate by double-entry bookkeeping, and the “fundamental rule of bookkeeping” is that every transaction must sum to zero, according to the rule that “assets minus liabilities equals equity”: the gap between the value of your assets and the value of your liabilities is your net worth. For each individual transaction, this means that the sum of Assets minus Liabilities minus Equity must equal zero: if that doesn’t apply, then you’ve made an accounting error.

If you try modelling lending from Reserves in Ravel, so that Reserves fall and Deposit accounts rise, Ravel tells you that you have made an error—see the first row in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Modelling the accounting of "the Money Multiplier" in Ravel

The second row is valid—but how does the borrower get the money? The only way this can happen is if the loan is in cash: then the borrower’s debt rises, as shown by Figure 10, but so does the borrower’s holdings of cash: see Figure 11.

Figure 11: "Money Multiplier" lending from the borrower's point of view

Now ask yourself: when’s the last time you—or anyone—got a loan from a bank in cash? It may well have happened in the 19th century, but during the 20th—and certainly since banking became electronic—banks lend by crediting borrowers’ deposit accounts directly. This is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12: Real-world lending: Loans create Deposits

Reserves play no active role in this process: banks had to get additional Reserves because of Required Reserve Ratio rules, when those existed (they were abolished during Covid), but even then it was an after-the-event action.

Why don’t members of the FOMC know this? Because they were trained in Neoclassical economics, which treats the economy as a barter system. Money plays no significant role in its vision of the economy, and Neoclassical macroeconomic models do not include banks, or private debt, or money.

So the Federal Reserve is incompetent, not because its members are stupid, but because they are experts on a theory of economics which is wrong.

In their theory, credit—private bank lending—plays no significant role in the economy, because in Neoclassical economics, lending is a “pure redistribution” of existing money, which “should have no significant macroeconomic effects” (Bernanke 2000, p. 24).

The real world makes a mockery of this claim. Credit is a huge and volatile component of both aggregate demand and aggregate income: if credit increases, then unemployment falls, and vice versa. The correlation between credit and unemployment between 1989 and 2014 is a staggering negative 0.89. But private debt also causes crises: credit-driven demand increases private debt, and it can lead to people and companies ceasing borrowing—and in fact paying their debt levels down—which leads to a slump. This is what caused The Great Recession, and Neoclassical economists had no clue that it was about to happen.

Then government debt increased as a side effect: tax revenues plunge, and social security payments rise. A huge component of government activity is non-discretionary, so that the economy tends to drive the government rather than vice versa: the correlation between unemployment and the government deficit between 1989 and 2014 is positive 0.79—see Figure 13.

Figure 13: Excessive private debt is the cause of economic booms and busts

One of the consequences of the institutional incompetence of The Fed is that the government is giving the financial sector far too much money. With interest rates on bonds and reserves—both of which are set by the FOMC—close to 5% p.a., outstanding government bonds totaling 110% of GDP, and Reserves being another 11%, the government is gifting the financial sector a sum equivalent to more than 6% of GDP every year. This is more than the finance sector got from the government during the days of sky-high interest rates under Volcker—see Figure 14.

Figure 14: Interest payments to banks by the government exceed 6% of GDP

There is absolutely no need to gift the finance sector this much government-created money. So back to Ted Cruz’s comment. While banks deserve some government funding to compensate them for running the country’s payments system, this is too damn much. But it could easily be reduced by the Fed cutting interest rates. It put them up because Neoclassical economic models claim that rising interest rates reduce inflation, but this is another myth: the country which got the Covid inflation under control fastest was Japan—and while it did increase its interest rate on Reserves, this was just three times, and from minus 0.1% to plus 0.5%!

Figure 15: Policy rates in the USA and Japan

Inflation fell for other reasons—primarily the end of the Covid supply shocks. The increase interest rates on bonds and reserves feathered the finance sector’s nest, but did nothing good for the overall economy.

So Ted, keep lobbying for lower rates on government bonds and bank reserves. And maybe see if you can get some competent, non-Neoclassical economists appointed to the FOMC.

References

Bernanke, Ben. 2007. "Monetary Policy Report to the Congress." In. Washington: Federal Reserve.

Bernanke, Ben S. 2000. Essays on the Great Depression (Princeton University Press: Princeton).

———. 2004a. "The Great Moderation: Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke At the meetings of the Eastern Economic Association, Washington, DC February 20, 2004." In Eastern Economic Association. Washington, DC: Federal Reserve Board.

———. 2004b. "Panel discussion: What Have We Learned Since October 1979?" In Conference on Reflections on Monetary Policy 25 Years after October 1979. St. Louis, Missouri: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Campbell, Sean D. 2007. 'Macroeconomic Volatility, Predictability, and Uncertainty in the Great Moderation: Evidence from the Survey of Professional Forecasters', Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 25: 191-200.

Fisher, Irving. 1933. 'The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions', Econometrica, 1: 337-57.

FOMC. 2009. "Meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee on December 15–16, 2009." In.: Federal Reserve.

Keen, Steve. 1995. 'Finance and Economic Breakdown: Modeling Minsky's 'Financial Instability Hypothesis.'', Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 17: 607-35.

———. 2007. "Debtwatch." In Steve Keen's Debtwatch.

Obama, Barack. 2009. "Obama’s Remarks on the Economy." In. New York: New York Times.

Summers, Peter M. 2005. 'What Caused the Great Moderation? Some Cross-Country Evidence', Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review, 90: 5-32.

All of the things you suggest we do are well and good. However, their effect does not recognize the core of the problem and how to resolve it. As you have said before every year the banks create upwards of 97% of all new money. Thats a monopoly percentage. The problem is the monopoly paradigm of Debt Only as the sole form and vehicle for the creation and distribution of new money, and its solution is the strategic integration of Monetary Gifting into the Debt Only system with a 50% Discount/Rebate policy AT THE POINT OF RETAIL SALE. Doing that macro-economically (because EVERYONE participates in and/or is effected by the price at retail sale) doubles potential demand while simultaneously implementing beneficial price and asset deflation thus invalidating the quantity theory of money (the heads of the orthodox explode).

This policy actually integrates private finance back into the actual economic process as presently it is a wholly exterior cost adding parasite on the actual productive economy because Debt/loans are always pre-production or post retail sale. So for instance with the 50% Discount/Rebate policy a $500k house is reduced to $250k at retail sale and then at the newly recognized retail point of Finance, i.e. your mortgage payment, one's payment is reduced to the quivalent of a $125k loan while the bank receives its full payment on the $250k loan.

Presently we are stupider than the ancients who used periodic debt jubilees to reset their economies. The problem with that was it enabled finance to re-dominate everyone for another 70+ years because it didn't change the paradigm of Debt Only. What we need is to become smarter than the ancients by strategically integrating continual debt jubilee into the economy with the 50% Discount/Rebate policy at retail sale.

Thanks for helping to clarify the interest on reserves question for me. Somewhat bizarrely it had been on my mind in the last couple of days before your post, because I had been thinking about how the US economy has managed to defy most predictions and weather the storm of higher interest rates and QT. Clearly there are significant factors keeping it afloat, and paying 6% of GDP per year to the banks (and money market funds now as well?) will be one of these.

Re: "Neoclassical macroeconomic models do not include banks, or private debt, or money." I really struggle to believe that any serious thinker could create such a model or be taken seriously if they said something like that publicly.

I can still remember reading about the problems with lending in the US housing market in a British financial magazine...in 2006 and 2007. They clearly understood and laid out what was going to happen. It never made sense to me that financial journalists could predict this but economists (with one or two notable exceptions!) couldn't.