The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank has many parents. Twitter is alight with fingers pointing at venture capitalists for starting a run against a bank whose many wealthy customers had deposits far in excess of the maximum that is guaranteed in the event of a bank failure ($250,000). Michael Hudson blames the aftermath of the Fed's Quantitative Easing, which boosted asset prices—including bonds—via massive bond purchases by the Fed and matching low interest rates. Alf at the Macro Compass blames the failure of the bank to hedge its risk to changes in interest rates. Frances Coppola blames the failure to carry sufficient capital to cope with a bank run.

Running through all these explanations is the impact of rising interest rates on bank solvency. In this post, I want to give a simple explanation of why this can cause systemic failure—not just to a single bank like SVB, but to the entire banking system.

When inflation returned to the economic scene after a 3-decade absence, The Fed fought it the only way it knows how—by raising interest rates on government bonds. Its mainstream economic models, which ignore banks, debt and money—weird, eh?—predicted that raising interest rates would lower the public's expectations of inflation, and this would cause actual inflation to fall. Problem solved—in mainstream economic model world.

Meanwhile, in the real world, rising interest rates on government bonds can cause banks to go insolvent. SVB was the canary in the coal mine here, but the factor that brought it undone is shared by all financial institutions, because government bonds are a major component of their assets. When interest rates rise, bond values fall, and this can drive financial institutions into insolvency—where their Liabilities exceed their Assets.

I want to give a very simple explanation of why this can lead to systemic disaster—and, therefore, why it is vitally important that the Fed stop using economic models that ignore the banking sector.

The basic mechanism is extremely simple: bond prices move in the opposite direction to interest rates. A bond promises to pay a fixed sum every year in return for buying that bond for a fixed price. If the bond costs $1000 and the "coupon rate" is 3%, then the bond issuer—the Treasury in the case of government bonds—pays $30 each year to the bondholder.

If interest rates rise, to say 5%, then this bond cannot be sold for its $1000 face value. The most extreme case here are "Consol" bonds, which never expire: a Consol's price is the fixed sum it pays each year, divided by the market interest rate. If that is 3%, then the $30 the bond pays every year is valued at $30/0.03, which is $1000—its face value. But if the market interest rate rises to 5%, then the sale price of the bond will be $30/0.05, which is $600. The bond's value falls by $400.

To illustrate why this is a serious problem for the banking sector in the current policy regime of rising interest rates, I've built a very simple Minsky model in which all bonds are Consols, banks don't hedge their risk, and where banks instantly write down the value of Bonds when interest rates rise.

The real world is far more complicated than this of course: almost all bonds are fixed term, so the impact of rising interest rates on their value isn't as extreme; banks do hedge their interest rate risks (Alf's post explains this very well) and they don't instantly "mark to market" (Frances Coppola's post gives a nice account of what they do instead). But the systemic factors remain. Its arguable too that, though an individual bank can hedge its risk, the banking system as a whole can't; and while the whole system can delay a day of reckoning with falling asset values, it can't avoid that day while interest rates remain well above those paid by the bonds they own.

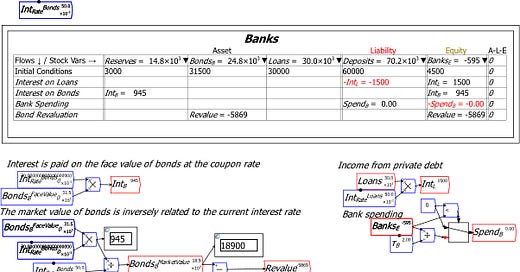

The model has just 4 stocks and 4 flows. The stocks are bank Reserves, Treasury Bonds owned by the banking sector, Loans to the Private Sector, and the Deposits of the public. The initial values are such that the banking sectors Assets well exceed its Liabilities, so that it is in positive Equity—which is a requirement for every individual bank, let alone the entire banking sector.

Figure 1: The financial stocks and flows in the model before interest rates change

The flows are interest on outstanding private sector debt, interest on government bonds, spending by the banking sector on the non-bank private sector, and bond revaluation. Interest on outstanding private sector debt, and interest on government bonds, remain constant because I've left new bank loans out of the model, and I've omitted factors that alter bank bond holdings as well (primarily the selling of bonds by banks to non-banks, and purchasing of bonds by The Fed). Bank spending is proportional to Bank Equity: I've assumed banks spend half their (short-term) equity every year, so their spending starts at $2,250 billion per year.

Revaluation of Bonds starts at zero, because the prevailing interest rate is the same as the interest rate paid by existing government bonds, which is 3%. The Equity of the banking sector stabilizes at $4,890, because at that point its spending is identical to its interest income ($2,445 billion per year).

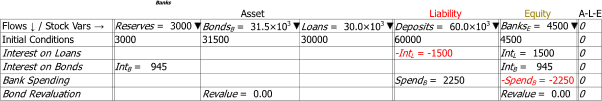

Once the banking sector's equity has stabilized, I increase the prevailing interest rate from 3% to 5%. This is much faster than The Fed's 0.25% monthly interest rate hikes, but again, the function of this simple model is to show what the systemic implications of these rises for the whole banking sector.

The banking sector goes into negative equity.

I emphasise that nothing this extreme will happen in the real world: this model is just to illustrate the key point that rising interest rates reduce the value of existing government bonds, and that this will affect the solvency of bondholders.

In the real world, banks sell much of their bond portfolio to non-banks, which reduces their exposure to effects like this—though that exposure doesn't go away, but is instead felt by the non-banks that bought the bonds. Banks hedge their exposure to movements in fixed rates too, as Alf explains—but as we should have learnt from the Global Financial Crisis, hedging risk doesn't mean eliminating it. Instead, somewhere else, someone else is on the end of a losing trade. The fall in the value of bonds still affects the solvency of the system.

Figure 2: A rate rise drives the banking sector into negative equity

SVB was the canary in this event—or perhaps the turkey—because it had an extraordinary level of government bonds on its books. But the financial sector as a whole is the real turkey that The Fed is inadvertently roasting as it thinks it is reducing inflationary expectations.

It's The Fed that deserves to be roasted instead, for attempting to manage the financial system using models that ignore banks, debt, and money.

Great assessment Steve

I'm trying to get my head round a possible route to contagion in the real (rather than financialized) economy with respect to the approach that Benjamin Graham used in valuing securities at the time of the Great Depression. If I recall correctly his approximate method to valuing a security's worth with some margin of safety was essentially (Current Assets) - (Total Liabilities).

Now suppose that we have an 'innocent' profitable company working in the real economy carrying a variety of current assets that include cash (and equivalents), accounts receivable (less bad debt provisions), a bunch of inventory, and some pre-paid expenses.

As I understand the bail-in conditions imposed on creditors by Dodd-Frank of 2010 any depositor holding deposits above $250k now, instead of holding a corporate asset of cash, now holds an equivalently sized corporate liability as it it required by law to bail-in the bad bank.

Am I missing something here or is this just the end-game in which a financialized economy kills off whatever remains of a the US's industrial economy, leaving corporations whose only assets are whatever physical inventory they carry when the merry-go-round stops?