Musk's Perfect World: How would it work?

Applying iterative design to Musk's proposed zero deficit world

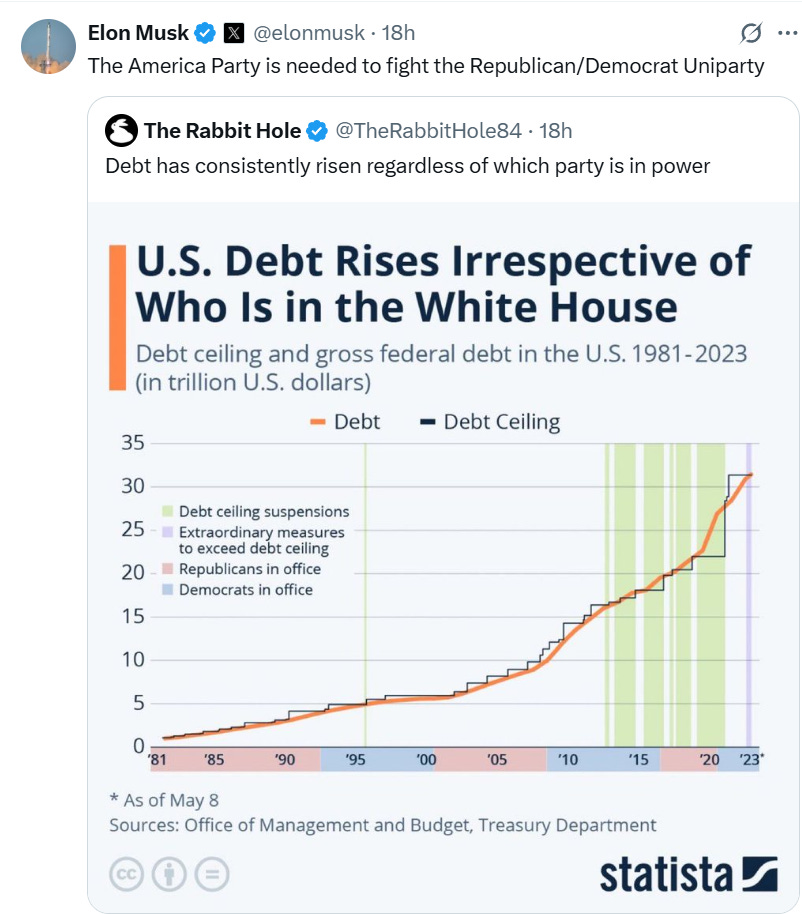

Anyone who thought that the falling out between Trump and Musk was staged got a wake-up call last week, when Musk announced that he was going to create a new political party–the America Party–to fight both the Republicans and the Democrats over government debt and deficits.

The dividing line between Trump and Musk is now clear. Musk thought that Trump was dedicated to eliminating the government deficit, but the “One Big Beautiful Bill” put paid to that. Though it slashed spending in many areas, it also increased the debt ceiling by $5 trillion, and it cut taxes on the rich by far more than it cut spending on the poor–thus increasing the deficit.

Trump was fine with that; Musk was livid. He is clearly determined to eliminate the deficit and reduce government debt. Since he believes that neither incumbent party will do it, he’s forming his own.

Musk, as he put it in another context, seems hell-bent on achieving a world in which the government never runs a deficit “if it is the last thing I do on this Earth”.

If he succeeds, what sort of world would it be?

In this post, I use my Ravel software (https://patreon.com/ravelation) to imagine such a world: one where all government spending is financed by taxation, and, for good measure, government debt has been eliminated, so that the government isn’t paying any interest on debt either.

Would this world work be perfect from the get-go? Or would it, like Spacex’s rockets, need a process of iterative design? It took numerous iterations before Spacex went from proof of concept (“Starhopper”) to an almost final design (“Starship”). Would Musk’s perfect world be perfect on the first try, or would it need iterations too? Let’s find out.

“Starhopper”: A balanced budget government!

The Table below shows the simplest possible view of such a world. There are just 5 financial operations:

Banks lend to the non-bank private sector;

The non-bank private sector pays interest on this debt;

Banks spend on the non-bank private sector; and

The government taxes, and spends, on the non-bank private sector, following the express rule that all spending is financed by taxation.

Simple equations, built using Ravel’s flowchart technology, convert this from an accounting framework into an economic model:

GDP is generated by the turnover of existing money

Interest is paid on loans

Banks spend out of their short-term equity

Banks make loans at a variable rate proportional to GDP

The government spending is also a variable proportional to GDP

The government levies taxes that are precisely equal to its spending.

So, how would life be in this world?

It would be functional, but there is one literally inescapable problem: the non-bank private sector (represented by the bank account “Depositors” in the above table) is necessarily in negative financial equity.

They start out in negative financial equity, with $100 in liabilities and $90 in assets, for a financial equity of minus $10.

Then, no matter how the economy twists and turns, the non-bank private sector remains in negative financial equity, and it is precisely equal to the positive financial equity of the banking sector.

The inevitability of negative financial equity

Negative financial equity for the non-bank private sector is a necessity, because of an absolute requirement that banks must be in positive financial equity: their financial assets must exceed their financial liabilities. Any bank which finds that its liabilities exceed its assets is technically bankrupt.

This is both a rule enforced by governments–to establish a bank, you must, inter alia, show that you have substantial financial assets and no (or very few) liabilities–and it is also something that is intrinsic to banking. Ultimately, the way that banks profit is by leveraging their equity–by creating income-earning assets, up to some risk-tolerance-limited multiple of their equity. That equity has to be positive for that to work.

This fundamental necessity for banks interacts with the fundamental nature of financial assets. One entity’s financial asset is another entity’s financial liability, so that the sum of all financial assets and liabilities is zero. Therefore, the non-bank sector of the economy must be in negative financial equity.

The non-bank sector of the economy is the sum of government and the non-bank private sector. With the government always running a balanced budget, and having no debt, the government’s financial equity is zero. Therefore, the financial net worth of the non-bank private sector is negative, and precisely equal in magnitude to the positive equity of the banking sector.

In words that someone trained in physics should understand, this is the by-product of a conservation law: since for every financial asset there is a matching financial liability, the sum of all financial net worths is zero. So, if one segment of society is in positive financial equity, the rest of society is in negative financial equity to it, of precisely the same magnitude.

There is no way out of this financial rule: you can no more evade this rule of accounting than you can disobey the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

But let’s face it: no-one enjoys being in negative financial equity. While you can still earn a viable income when in negative financial equity, you’re always haunted by the fact that your liabilities–your debts–exceed your assets.

So what is the private non-bank sector likely to do in that situation?

Here we can turn to history: when its financial net worth was negative, or heading in that direction, the private non-bank sector borrowed money from the banks to speculate on the value of nonfinancial assets.

The Nonfinancial Assets Trap

Nonfinancial assets are things like shares and houses. Even if people buy shares with margin loans, and houses with mortgages, the shares and the houses themselves are assets to their owners, and liabilities to no-one.

When we put a monetary value on those assets, based on the price they would realise if we sold them into the current market, then we get a necessarily positive sum. Add this positive sum to your negative financial equity, and you come out with a positive figure. This lets the private non-bank sector sleep easy at night, comfortable in the knowledge that its overall net worth is positive.

That is, until the private non-bank sector wakes in fright one morning, to see that the value of its nonfinancial assets have plunged, in a stock market or housing market crash.

This is also inevitable in Elon’s “perfect” world, because the way we actually purchase nonfinancial assets is by taking out a loan from a bank, and handing over the money created by the loan to the seller. Even at the most conservative financial times in history–the 1950s and 1960s–mortgage debt accounted for 70% of the purchase price of the average house. Margin debt is not quite so important for share purchases after Glass-Steagall, but before it, many share market speculators bought their shares with a margin loan covering 90% of the purchase price.

This means that, effectively, the new debt that borrowers are willing to take on, which accountants call “Credit”, sets the price level for nonfinancial assets. Therefore, the change in credit sets the change in the price level for nonfinancial assets.

Mainstream “Neoclassical” economists deny this, using the fetchingly named “Modigliani-Miller Hypothesis”, but the data makes a mockery of it. A century’s worth of margin debt data shows that changes in margin credit drive changes in share prices; 80 years of mortgage debt data shows that and changes in household credit (which is mainly new mortgages) drives change in house prices.

If this kept on happening, so that asset prices rose forever, this wouldn’t necessarily be bad. But there’s a trap. This process relies upon debt accelerating forever.

With new margin debt driving share prices, and new mortgage debt driving share prices, the level of debt has to accelerate forever to sustain rising prices for nonfinancial assets. But, in the absence of outside interference, nothing can accelerate forever. So a bust inevitably follows a boom, as accelerating debt gives way to decelerating debt–and ultimately, falling debt.

This happened most brutally in The Great Depression, when margin debt let people buy shares on a 10% deposit. When prices fell 10% in one day, many speculators and banks were wiped out. That kept on going until share prices had fallen 90% from their peak.

It happened to house prices in the Global Financial Crisis–until the Government intervened with QE and big government deficits. But we’ve ruled this out in Musk’s perfect world.

The outcome is that booms and busts, driven by bubbles and crashes in private debt, occurred regularly when governments either reduced their debt by running surpluses, or maintained balanced budgets for extended periods of time. Credit–the change in private debt–boomed for a while, but then turned negative, driving the economy into a crisis. It happened most severely in the “Panic of 1837”, the 1873 Depression, and the Great Depression, but crises caused by negative credit were a regular feature of the “Small Government” 1800s.

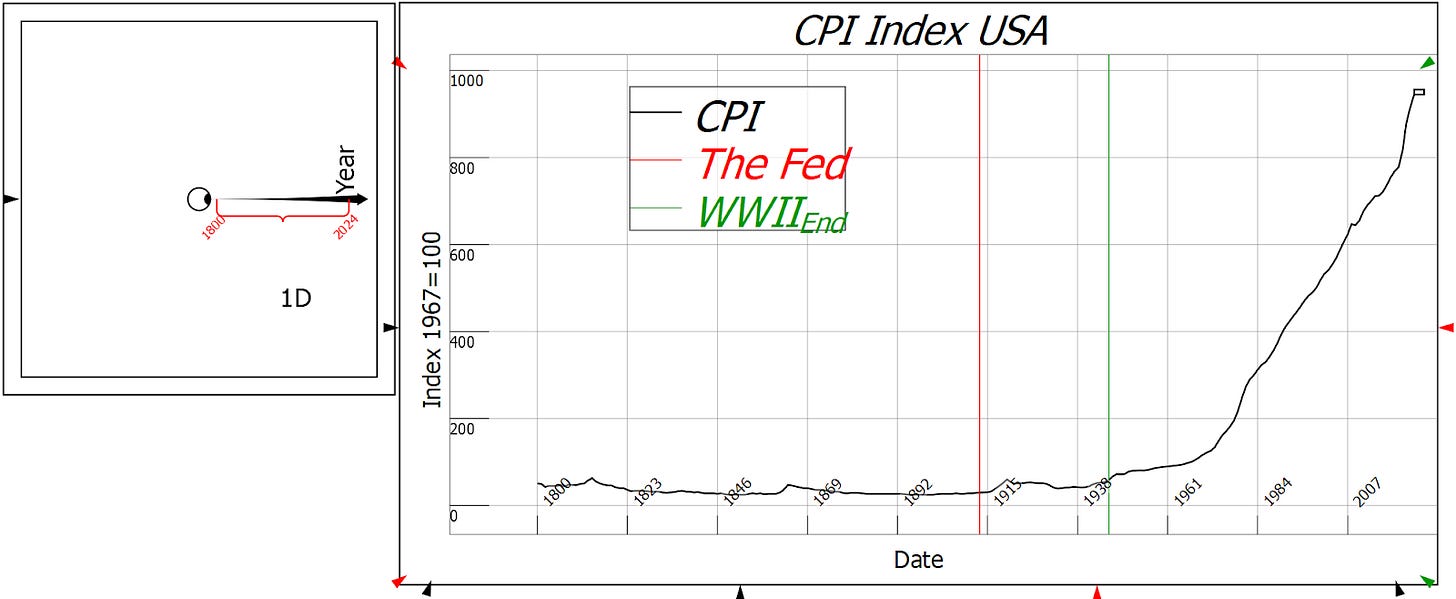

We can see this in the inflation data for the 19th century as well, when US government spending was a tenth of what it is today, and the government regularly reduced its debt to zero. People think this meant price stability: just look at the inflation now, versus the stable price level before WWII!

But zoom in on the 19th century, and you see that rather than stable prices, there was higher inflation during booms, and sustained deflation during slumps.

Financial crises were also about twice as frequent during the 19th century, when government spending was about 10% of today’s levels (3% of GDP versus 30% of GDP), as they have been since the days of “Big Government" commenced during WWII.

They were also far more severe than we’ve experienced since Big Government. As Hyman Minsky said:

The most significant economic event of the era since World War II is something that has not happened: there has not been a deep and long-lasting depression. As measured by the record of history, to go more than thirty-five years without a severe and protracted depression is a striking success. Before World War II, serious depressions occurred regularly. The Great Depression of the 1930s was just a “bigger and better” example of the hard times that occurred so frequently. This postwar success indicates that something is right about the institutional structure and the policy interventions that were largely created by the reforms of the 1930s. (Minsky, Can It Happen Again?, p. xix)

Clearly, a system with near-inevitable serious financial crises is not a good system. Swapping the perceived dangers of excessive government debt with the actual danger of private debt causing regular crises is not a design improvement.

So, we need to change the design of Starhopper so that the non-bank private sector can be in positive financial equity indefinitely? Is that possible?

Well yes, it is. For the private non-bank sector to be in positive financial equity, the government must run sustained deficits.

This would be a hard lesson for Musk to learn. But let’s pretend that he does, and allows the next iteration to include government spending exceeding taxation–but without issuing bonds, and therefore without interest payments. How does this rocket fly?

Starship 1: Adding a deficit to Starhopper

Government spending and taxation equations are now separate decisions, and if the government spends more than it takes back in taxation, it runs a deficit–the thing that Musk is trying to eliminate, but which the Starhopper experiment taught him was necessary.

With no bonds being issued, or interest paid by the government, there is no danger of runaway government debt or interest payments. But can the system work without them?

It appears so. The main impact of the government spending more than it takes back in taxation is that the government sector goes into negative financial equity–but this is the intention of the redesign. Then, for precisely the same reason that banking sector positive equity puts the non-bank sectors (the government and the nonbank private sector) into negative financial equity, the government’s negative financial equity enables both the banking sector and the non-bank private sector to achieve positive financial equity.

Can the government cope with negative financial equity? Yes, for two reasons.

Firstly, the government has enormous positive nonfinancial assets: the state apparatus, the justice system, the military, government undertakings like public schools and hospitals… Their existence backs up the government’s negative financial position. Secondly, in some ways a country is defined by the borders within which its governments liabilities are accepted in commercial transactions. The capacity to issue liabilities which are accepted by third parties in their own transactions is the mark of a government.

But are there any bad consequences elsewhere in the system?

There is one, though it’s mainly cosmetic: the Treasury’s account at the Central Bank goes into overdraft. In the figure below, the $185 positive financial equity of the non-government sector (4 for the banks, 181 for the non-bank private sector) is matched by the $185 overdraft (marked in blue) that the Treasury has at the Central Bank.

Could we fix that glitch? There’s nothing unsustainable about the government running up an overdraft at a bank which it owns, and which doesn’t charge it interest. But it looks dodgy. Can we get a better looking result–one in which the government doesn’t run an overdraft at its own bank?

Yes: the Treasury could issue Bonds equivalent to the Deficit, and sell them to the Central Bank. We try this design in the 3rd iteration, “Starship 2”.

Starship 2: Selling Bonds to The Fed

The Treasury’s account at The Fed avoids an overdraft because revenue inflow from bond sales to The Fed precisely equals the outflow caused by the deficit.

This works. The Treasury’s account at The Fed now stays out of overdraft (at zero), while the Fed accumulates Treasury Bonds as assets, and these are precisely equal to its one positive liability, bank reserves (which are also created by the government deficit).

Are there any problems with this design? It works, but it ends up being a rough deal for the Banks, because the assets that a government deficit creates for them, Reserves, don’t earn an income (in this hypothetical model), and can’t be traded.

This suggests a solution: why not have the Treasury sell the bonds to the private banks, rather than to The Fed? We’ll try this out in Starship 3.

Starship 3: Sell Bonds to the Banks

The Treasury would have to pay interest on the bonds to make the deal attractive to the banks, but that payment would reward the banks for maintaining the payments system as a semi-public-service, so they should get something for that. The Treasury would then issue bonds equivalent to the deficit, plus interest on existing bonds held by the banks.

But won’t this mean that government debt and interest payments explode? This is the fear that drove Musk to redesign the government in the first place. But you never know till you do a test, so let’s fly this rocket, with Musk no doubt expecting it to crash.

But surprise, surprise: it doesn’t crash! With both the banks lending out 3% of GDP each year in new loans, and the government spending 3% of GDP more than it takes back in taxation, both private and government debt levels stabilize relative to GDP.

So Musk’s fears were unfounded. Why? Because increasing private and public debt also cause an increasing money supply, which enables GDP to grow. Ultimately, both grow at the same rate, and the ratio–which Musk assumed would explode–actually stabilises.

With these reforms, we are back to the system we actually have. But of course the actual system looks nothing like this. Private debt levels ballooned until the Global Financial Crisis, while government debt fell from the end of WWII until the beginning of the 1980s–and then leapt when the GFC hit.

So what else is going wrong in the real world? Here I’m going to switch from rockets to cars–something with which most of us have experience.

So what’s the solution?

Our problems with the post-WWII system have largely come about because we have people in charge of the system who don’t understand it. It’s like designing a superb sports car, and then putting an arrogant amateur driver at the wheel. He’ll crash the car and then blame the car rather than himself.

Even worse than having an arrogant amateur behind the wheel, with Neoclassical economists managing The Fed and The Treasury, we have people with a false model of how the monetary car actually works.

Neoclassical economists believe that private debt and credit don’t matter, while they obsess about government debt and deficits. Consequently, they let private debt explode after WWII, while trying to lower government debt.

They recommended eliminating the deficit and cutting government debt, which encouraged the non-bank private sector to indulge in three great speculative bubbles: the 1987 stock market bubble and crash, the internet bubble of the 1990s, and then the Subprime Bubble and burst of 2000-2007.

They rescued the banks, rather than the mortgage holders, after the GFC.

The only reason that there hasn’t been another giant speculative bubble after the GFC–well, apart from Bitcoin and the Stock Market–is that the non-bank private sector’s appetite for debt appears relatively quenched by the astronomical level of private debt today, when compared to the bubble-free days of the 1950s.

What we should be doing, rather than eliminating government deficits–which, as we’ve found by iteration, is akin to sticking a plug into a rocket engine–is enforcing what Hyman Minsky called “a “good financial society” in which the tendency by business and bankers to engage in speculative finance is constrained” (Minsky 1982, Can “It” Happen Again?, p. 70)”.

That, and not the termination of government deficits and the abolition of government debt, is the redesign of the financial system that we actually need.

If the government is truly monetarily sovereign...why does it need to tax at all? The answer of course is inflation which The FED is (supposedly) mandated to control, but a closer look at The Fed (and the entire monetary system) is that The FED's charter is actually designed to make the world safe for private banking...whose monopoly paradigm of DEBT ONLY is THE PROBLEM.

So how do you actually control, no END inflation? Two things:

1) You amend The FED'S charter to create monetary gifting in other words distribute MONEY NOT DEBT at retail sale with a policy of a 50% Discount/Rebate at that point thus implementing beneficial deflation.

2) You do an honest calculation of inflation and allow it be 2-3% per annum while indexing the retail discount to 52-53% and then tax enterprise at a rate of 100% on any revenue they may get over the 2-3% allowed increase. The FED can still create reserves and banks can still create debt of course, but its rate of increase is greatly reduced by the paradigm changing supplemental accounting operation of a monetary gifting policy at retail sale.