Money and Macroeconomics from First Principles, for Elon Musk and Other Engineers Chapter 03 Loanable Funds

Chapter 03. Loanable Funds

In the model of banking known as Loanable Funds, banks do not lend directly to borrowers, but instead act as intermediaries between savers—typically households—who supply Loanable Funds, and borrowers—typically firms—who demand them:

a financial intermediary stands between the two sides of the market and helps move financial resources toward their best use. Commercial banks are the best-known type of financial intermediary. They take deposits from savers and use these deposits to make loans to those who have investment projects they need to finance. {Mankiw, 2016 #6107`, p. 593}

This model has households saving, and firms borrowing, with banks functioning as intermediaries:

Saving is the supply of loanable funds—households lend their saving to investors or deposit their saving in a bank that then loans the funds out. Investment is the demand for loanable funds—investors borrow from the public directly by selling bonds or indirectly by borrowing from banks. {Mankiw, 2016 #6107`, pp. 72}

This can be represented in Ravel by showing the banking sector acting as an intermediary between households who save, and firms which borrow—see Figure 7. Bank income is generated by a Fee charged to Households.

Figure 7: Loanable Funds without Government Bank Godley Table

Loans do not appear in this table, because in Loanable Funds, Households are the lenders rather than banks. Loans are therefore assets of the Household sector, rather than the banks.[1] Figure 8 shows the Households Godley Table, in which DebtFirms is an Asset; it is a Liability on the Firms’ Godley Table.

Figure 8: The Households Godley Table

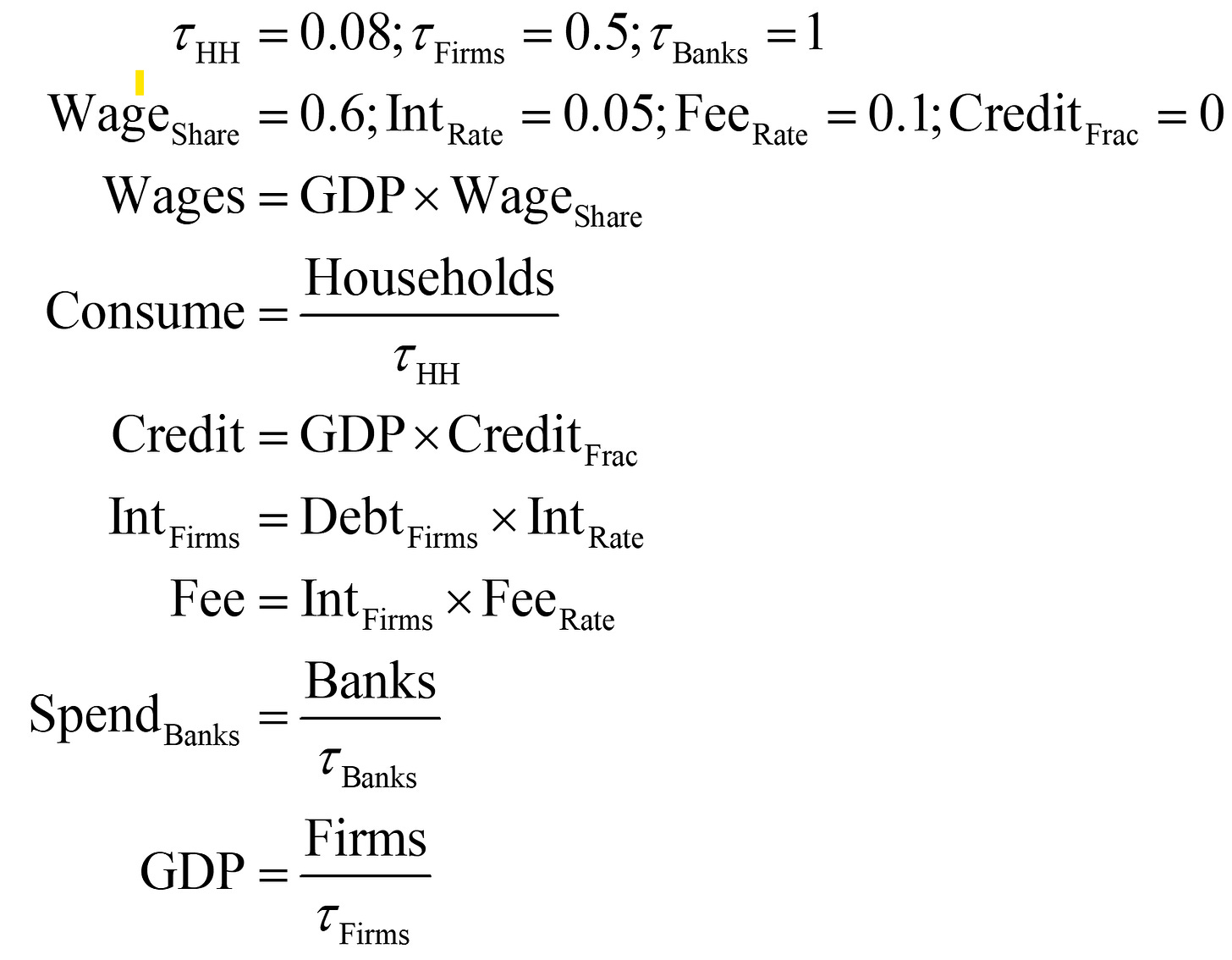

The parameters and flows in the model are defined on the canvas, as in Figure 5. Their initial values and equations are:

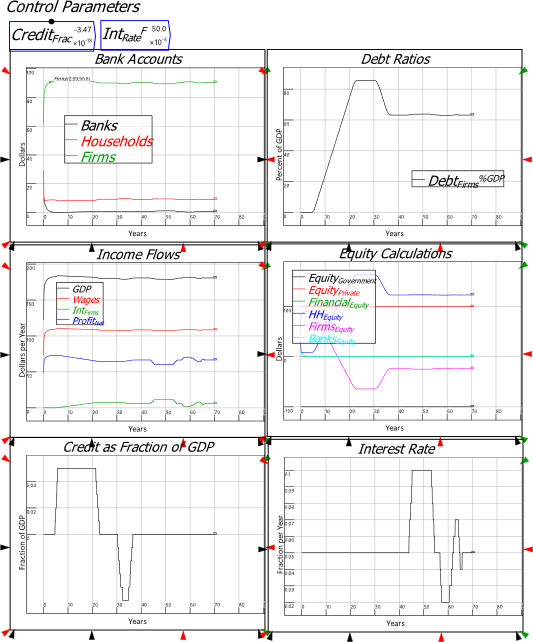

The model can now be simulated, and key parameters can be varied during the simulation—see Figure 9.

Figure 9: Loanable Funds with only private sector debt

This is clearly a sustainable system.

A government sector is added to this model by:

Adding a Government deposit account as an additional Liability for Private Banks;

Adding DebtGov as an additional Asset for the Household Sector; and

Adding the flows of government spending and taxation, bond sales, and interest payments on outstanding government bonds

This extension requires changes to the Banks, Household and Firms Tables, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Additional flows for Banks, Households and Firms[2]

A new Godley Table is also required for the Treasury—the component of the government that owns its deposit account at the Banks. The Government account is an Asset of the Treasury, and government debt—in the form of bonds sold to the Household sector—is its liability.

Figure 11: The Treasury Godley Table

The differential equations for this system are shown in Equation 5:

Figure 12 shows the standard requirement that the government must sell bonds equivalent to the value of the Deficit, plus interest on existing bonds.

Figure 12: The equations for Government finances

In this very simple model, the interest rate is a parameter. Making it a variable does not change the ultimate result, so in the spirit of “the best part is no part”, I don’t implement a variable interest rate.

Figure 13 shows a simulation of this model with a constant Deficit equivalent to 1% of GDP. It is clearly unsustainable: government debt hits 2,000% of GDP, and interest payments exceed 100% of GDP, even when modelling interest rates as fixed. Well before these levels are reached, and especially with variable interest rates, lending to the government by the private sector would cease, and the government would be bankrupt.

Figure 13: A simulation with a Deficit of 1% of GDP

Therefore, if Loanable Funds is an accurate description of how banks operate, then a fiscal crisis is inevitable if the government habitually spends more than it takes back in taxation, and government spending muse be reduced to be equal to, or less than, revenue from taxation.

However, there are strong arguments that Loanable Funds is a false model of how banks operate. An alternative model, known as Endogenous Money, is a minority position in the economic literature, but it was endorsed as correct by both the Bank of England {McLeay, 2014 #5066}and The Bundesbank {Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017 #5312} after the Global Financial Crisis.

The next chapter edits the model shown here to create a model of Endogenous Money creation, which I prefer to describe by the acronym BOMD, for “Bank-Created Money and Debt”.

[1] Loanable Funds cannot show money creation, which is explained in economics textbooks using the Money Multiplier and Fractional Reserve Banking models. These models have problems of their own, which I consider in a later chapter.

[2] There is a Central Bank table in this model, since Reserves are its Liability, but there are no flows in it. So for simplicity I have excluded it from this Figure.

Commercial agents deserve to get their full price, but does the individual have to pay that full price? What if a supplemental monetary accounting process paid for half of that price? Like with a 50% Discount (credit)/50% Rebate (debit) at retail sale. The commercial agent would get their full price and yet the individual would only have to pay half of the price, IOW resulting in beneficial price deflation, a doubling of the individual's purchasing power and the solution to inflation and chronic austerity of demand.

The long acculturated unconsciousness of the monopoly paradigm of Individual Full Payment/Repayment ONLY needs to be sent to the dust bin of history the same as Salvation Via Roman Catholic Sacraments ONLY was...with a Monetary and Economic Reformation.