From “Ricardian Vice” to First Principles

The concluding chapter in my forthcoming book Money and Macroeconomics from First Principles, for Elon Musk and Other Engineers

A first principles approach to economics reaches vastly different conclusions about the economy to those found in standard economics textbooks. This is because those textbooks are based, not on first principles, but on an economic paradigm which has failed both empirically and logically, but which refuses to die: Neoclassical economics.

Neoclassical economics began as a defensible alternative to the preceding Classical school of economics, which had been founded by Adam Smith, was perfected by David Ricardo, and then turned into an attack on capitalism by Karl Marx. The Classical school asserted that prices were set by the cost of production:

It is the cost of production which must ultimately regulate the price of commodities, and not, as has been often said, the proportion between the supply and demand: the proportion between supply and demand may, indeed, for a time, affect the market value of a commodity, until it is supplied in greater or less abundance, according as the demand may have increased or diminished; but this effect will be only of temporary duration. (Ricardo 1817, p. 382, Emphasis added)

The Neoclassical School turned Ricardo on his head, arguing that supply and demand did indeed regulate price, through the concepts of marginal cost (supply) and marginal utility (demand). But though they turned Ricardo upside down, they maintained a practice that Schumpeter found so characteristic of Ricardo that he christened it “The Ricardian Vice”:

Ricardo's was not the mind that is primarily interested in either fundamentals or wide generalizations. The comprehensive vision of the universal interdependence of all the elements of the economic system that haunted Thunen probably never cost Ricardo as much as an hour's sleep. His interest was in the clear-cut result of direct, practical significance. In order to get this he cut that general system to pieces, bundled up as large parts of it as possible, and put them in cold storage—so that as many things as possible should be frozen and 'given.' He then piled one simplifying assumption upon another until, having really settled everything by these assumptions, he was left with only a few aggregative variables between which, given these assumptions, he set up simple one-way relations so that, in the end, the desired results emerged almost as tautologies… The habit of applying results of this character to the solution of practical problems we shall call the Ricardian Vice. (Schumpeter 1954, pp 472-73. Emphasis added)

One example of this vice is how Friedman “proved” that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”. He invented a fictional world in which, given his assumptions, inflation could only be caused by government money printing:

Let us start with a stationary society in which there are (1) a constant population with (2) given tastes, (3) a fixed volume of physical resources, and (4) a given state of the arts … (7) Any capital goods which exist are infinitely durable, cannot be reproduced or used up, and require no maintenance … (8) these capital goods … cannot be bought and sold. (9) Lending or borrowing is prohibited … (12) All money consists of strict fiat money, i.e., pieces of paper, each labelled "This is one dollar." (I3) To begin with, there are a fixed number of pieces of paper, say, 1,000…

Let us suppose that these conditions have been in existence long enough for the society to have reached a state of equilibrium. Relative prices are determined by the solution of a system of Walrasian equations. Absolute prices are determined by the level of cash balances desired relative to income …

Let us suppose now that one day a helicopter flies over this community and drops an additional $1,000 in bills from the sky… (Friedman 1969, pp. 2-4)

If you accept these assumptions, then the only conclusion you can reach is that money creation by the government—"helicopter money”—causes inflation. But these assumptions leave out critical aspects of the real world. Lending and borrowing exists, so there are two sources of domestic money creation, not just one. Population is changing, as are physical resources and technology. Capital goods can be produced, and they do wear out. The economy is never in equilibrium.

There is no necessity to make absurd assumptions like Friedman’s to build mathematical models of the economy. As I have shown in this book, starting from first principles is relatively easy, and leads to a dynamic, non-equilibrium vision of the economy which is far more realistic than Neoclassical economics.

We desperately need this approach to take over from the Neoclassical, because its false assumptions have led to false conclusions about how real-world capitalism actually operates, and policies based on these false conclusions have done enormous harm to capitalism. But economists themselves will not overthrow their own false paradigm.

In part, this is to be expected: it’s how all academic disciplines actually behave, as Max Planck realized when he failed to persuade any of his fellow physicists to adopt quantum mechanics, after he had developed it to solve the “black body radiation problem”:

It is one of the most painful experiences of my entire scientific life that I have but seldom—in fact, I might say, never—succeeded in gaining universal recognition for a new result, the truth of which I could demonstrate by a conclusive, albeit only theoretical proof…

This experience gave me also an opportunity to learn a fact—a remarkable one, in my opinion: A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it. (Planck 1949)

Economics is worse than physics, because generational change, which is an essential step in escaping from a failed paradigm in sciences, does not occur in economics.

Paradigmatic anomalies in physics are eternal: once something is found that contradicts a paradigm, it exists forever. Existing practitioners who are wedded to the dominant paradigm will most likely refuse to abandon it, but their students won’t ignore the anomaly. They replace the diehards of the old paradigm when they do in fact die, and either devise a new paradigm that solves the anomaly, or adopt existing work like Planck’s. As Planck observed, once the adherents to a failed paradigm die, a “Scientific Revolution” occurs (Kuhn 1970).

Anomalies in economics are transient. The Great Depression was an anomaly from the point of view of Neoclassical economics: the economy shouldn’t fall into such a deep and prolonged slump. Some economists—notably Irving Fisher (Fisher 1933)and Hyman Minsky (Minsky 1982)—broke away from the mainstream as a result, but the mainstream ultimately forgot about it. This is an endemic dilemma in economics: unlike in physics, past failures of a paradigm can be forgotten, and the events that established its failure cannot be reproduced.

Another key reason that economics hasn’t undergone a Scientific Revolution from Neoclassical economics is that the Neoclassical paradigm (and also its Austrian/LIbertarian neighbor) paints a very seductive vision of capitalism as a perfect, self-regulating system. People behave rationally—which Neoclassicals have repackaged to mean that people are prophetic: they can predict the future using Neoclassical economic models. “Factors of Production”—Labor and Capital—are paid their marginal products, so that the distribution of income is meritocratic. Power is dispersed if one assumes the non-existent phenomenon of “perfect competition”. The economy reaches equilibrium, which must be good—who needs evolution anyway? When you’re “perfect”, why change?

Mainstream economists fall for this vision of capitalism as the perfect economic system, and become zealots for this vision, remaining committed to it even when they discover outright contradictions of it.

But in fact, the real strengths of capitalism are features that are absent from the Neoclassical paradigm. The economy is always evolving: it is not equilibrium that distinguishes capitalism from past social systems, but rapid evolutionary change. Similarly, capitalism’s real weaknesses are things which cannot even be expressed within the Neoclassical paradigm. Monetary finance is vital for a capitalist economy, but it can become a whirlpool of speculation which undermines the productive capacity of the physical economy. The distribution of income and wealth in a capitalist economy reflects power imbalances that are assumed away by “perfect competition” (which is a pre-requisite for the marginal productivity theory of income distribution). Climate change is trivialised because in a Neoclassical model, output can be produced without energy, or with energy playing only a relatively insignificant role.

If change does come to economics, it will be by a hostile external takeover, rather than an internal reform. Engineers can and should play a major role in this. We desperately need a realistic, first principles, system-dynamics, physics-compatible, money-aware approach to economics. Neoclassical economists will never develop this themselves.

Further Study

There is an enormous literature providing critiques of Neoclassical economics. The fastest way to come to grips with this critical literature is via my most well-known book, Debunking Economics (Keen 2011). It was written for a non-technical audience, and the publishers insisted on placing most of the figures in the book in a separate volume. The best version for engineers is the Kindle version with an orange cover (see Figure 62) which includes all the text and graphics in the one volume.

Figure 62: The best version for engineers. See https://www.amazon.com/Debunking-Economics-Digital-Integrated-Dethroned-ebook/dp/B09LQ9JJYP/

There are a handful of alternative analytic approaches under development as well, in addition to the approach I outline in this book. The two which I believe are most promising, which complement the approach I use, and which are based on techniques that engineers, mathematicians and physicists will find familiar, are Jamie Galbraith and Jing Chen’s Entropy Economics (Galbraith and Chen 2025), and Ole Peters and Alexander Adamou’s Ergodicity Economics (Peters and Adamou 2025).

Galbraith and Chen develop a new theory of value for economics, based on the Laws of Thermodynamics—Laws of which most economists are either blithely unaware, or arrogantly dismissive of their relevance to economics.

Figure 63: Galbraith and Chen's thermodynamically grounded approach to economics. See https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/E/bo239242610.html

Peters and Adamou apply the mathematical concept of ergodicity to economics, noting that economists make an indiscriminate use of the assumption that economic systems are ergodic, which they are not. They make a compelling argument that the basis of almost all of the errors of Neoclassical economics is the false assumption of ergodicity.

Figure 64: Peters and Adamou's non-ergodic approach to economics. See https://ergodicityeconomics.com/publications/. The book will be published in June 2025.

There is also the popular alternative approach to monetary economics known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Stephanie Kelton give the best exposition of MMT in The Deficit Myth (Kelton 2020).

Figure 65: Stephanie Kelton's accessible exposition of Modern Monetary Theory. See https://www.amazon.com/Deficit-Myth-Monetary-Peoples-Economy/dp/1541736184

The core of MMT is an explanation of how governments create fiat money, and this explanation is 100% compatible with the Ravel-based monetary models that I built in this book. However there is also an international trade component of MMT which, as I explain in the previous chapter, contradicts MMT’s fundamentally monetary approach to economics. After writing the Trade chapter, interactions with MMT advocates led me to realize that the MMT proposition that “Exports are a cost, Imports are a Benefit” has the same foundation as most, if not all, of the errors of Neoclassical economics: the ergodic fallacy.

Ergodicity, Neoclassical Economics, and MMT on Trade

An ergodic system is one in which the long-term average behavior of a single, moving system is the same as the average behavior of many identical systems taken at a single point in time. An ergodic system obeys Birkhoff’s Equation (Peters 2019, p 1216):

In such a system, the correspondence between the average behavior of a system over time, and the average of many identical systems at a point in time, lets you replace the difficult art of dynamic modelling with the much simpler expedient of probability analysis.

There are many physical systems which are ergodic, such as the movement of a gas in sealed container. Molecules in the gas collide with each other all the time, and the time path of any one molecule would be unimaginably difficult to track, let alone to model accurately. But over time, that molecule will occupy every possible location in the container, and the statistical average of the entire system of molecules at a point in time will correspond to the average of that individual molecule over time.

However, there are many systems that are not ergodic, and applying the assumption of ergodicity when analyzing those systems leads to disastrously false conclusions. The world expert on ergodicity as it applies to economics is Ole Peters, and he notes that “the prevailing formulations of economic theory make an indiscriminate assumption of ergodicity”:

Is the time average of an observable equal to its expectation value? At a crucial place in the foundations of economics, it is assumed that the answer is always yes — a pernicious error. To make economic decisions, I often want to know how fast my personal fortune grows under different scenarios. This requires determining what happens over time in some model of wealth. But by wrongly assuming ergodicity, wealth is often replaced with its expectation value before growth is computed. Because wealth is not ergodic, nonsensical predictions arise. (Peters 2019, p 1216)

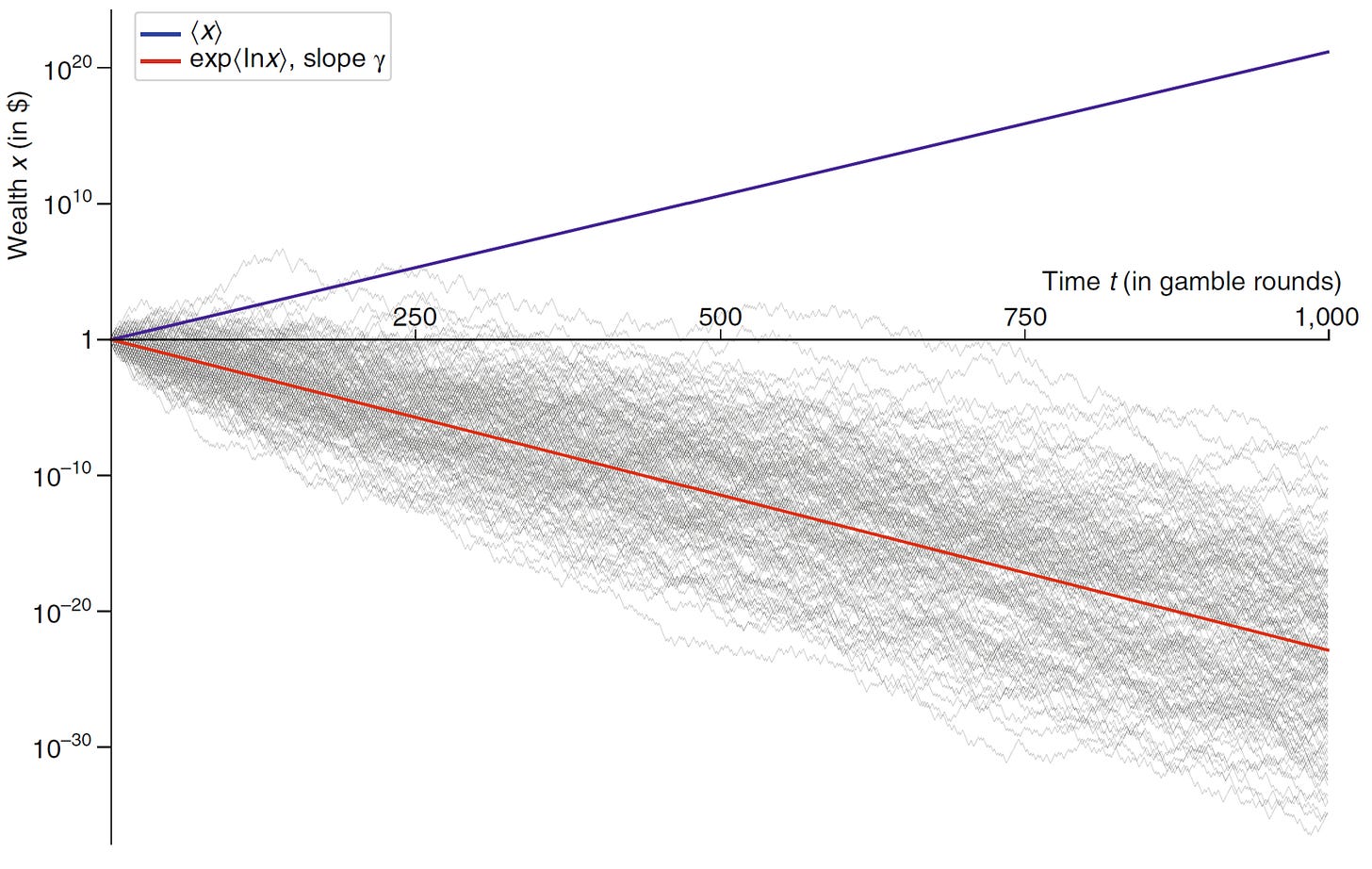

A simple illustration of this fallacy is what Peters describes as “The infamous coin toss”, an example of a non-ergodic process that he developed in 2011.[1]

Suppose you are offered a wager of betting $100 on a coin toss, where you will get $150 if it comes up heads, and $60 if it comes up Tails. At a point in time, the “Expected Value” of this gamble is $105, and economics textbooks—especially finance textbooks—will tell you that you should take the gamble. The Expected Value is:

Implicitly, Neoclassical economists assume that the coin toss gamble is “ergodic”: the time average of a sequence of gambles by one person over time can be replaced by the space average of many such gambles by many people at one point in time.

But this is false: the coin-toss process is non-ergodic.

If 100 people gamble $1 each at a point in time, then the average outcome is that 50 will receive $1.50, and 50 will $60. The average outcome will be the Expected Value of $105, as shown in Equation . But if one person bets $100, and then sequentially re-wagers the proceeds of that gamble over time, the average outcome is not $105, but 52 cents.

The reason is that, in the sequential gamble, you receive not the arithmetic mean of the two outcomes, but the geometric mean: you don’t add up the outcomes, but multiply them together. The simplest way to see this is to imagine that you throw 50 consecutive Heads and Tails pairs. If you throw a Head first, you turn the $100 into $150; then your next throw of Tails turns the $150 into $90: you lose 10% of your money every two throws. The time average is vastly different to the space average, even for such a simple process as a coin toss. The final outcome is:

This is one way in which casinos entice gamblers to their ruin. While the Expected Value approach used by Neoclassical Economists imply that 100 Heads would give the gambler $150 (100 times $1.5 on each wager), the gambler fantasizes about 100 Heads in a row, which would turn the original $100 into 4 million trilliondollars. The odds of that are of course vanishingly small, but the dream keeps the gambler in the casino until they are pumped dry. In the vast majority of gambles, the gambler will lose money, despite the outrageous returns from 100 successful gambles, and even from the Expected Value of the gamble, compounded over time—see Figure 66.

Figure 66: (Peters 2019, Fig. 2, p. 1219) 150 randomly generated sequential gambles, the average (red line) and the extrapolation of the Expected Value over time (blue line)

The same fallacy, though in a more complicated form, lies behind the fact encapsulated in Warren Mosler’s mantra that “Imports are real benefits and exports are real costs” (Mosler 2010, p. 59). It is true that, in a monetary purchase, the buyer exchanges something which costs very little to produce—money—for something which costs a large amount to produce—a manufactured good or service. In an international setting, with the manufacturer in one country (China) and the purchaser in another (the USA), it looks like a great deal: exchange US dollars for Chinese manufacturing goods, and America comes out ahead on each exchange. Hence Mosler’s declaration that “We [meaning the USA] are benefiting IMMENSELY from the trade deficit” (Mosler 2010, p. 60. Emphasis in original).

But if you keep doing it, you reduce America’s rate of investment. The good deal at a point in time becomes a catastrophe over time, as America’s investment rate falls. This is what has happened between the USA and China over the last forty years, and the outcome was nicely captured in a thought experiment by Warren Buffett.

Buffet imagined “two isolated, side-by-side islands of equal size, Squanderville and Thriftville” which produce and consume food only, on both of which 8 hours of work per person per day is necessary for survival. [2] Then the inhabitants of Thriftville double their workload to 16 hours per day, and sell the excess to the inhabitants of Squanderville in return for “Squanderbonds (which are denominated, naturally, in Squanderbucks)”. Squanderville residents stop working on their land, and rely instead solely on the creation of their currency and bonds, and food imports from Thriftville.

Eventually however, the Thrifts decide to sell most of their bonds to “Squanderville residents for Squanderbucks and use the proceeds to buy Squanderville land. And eventually the Thrifts own all of Squanderville.” The ultimate outcome is that the inhabitants of Squanderville:

must now not only return to working eight hours a day in order to eat--they have nothing left to trade--but must also work additional hours to service their debt and pay Thriftville rent on the land so imprudently sold. In effect, Squanderville has been colonized by purchase rather than conquest.

The example is stylized and fanciful, but the analogy fits what we have seen in the historical record of the United States’ negative trade balance with China, as outlined in the previous chapter.

Therefore, though “Exports are a Cost, Imports are a Benefit” is strictly true at a moment of time, pursuing that as a development strategy backfires. I do not in fact reject “Imports are a benefit and exports are a cost” as a statement of the instantaneous impact of buying manufactured goods from another country in return for paying them your own currency (see Figure 67).

Figure 67: A typical response from an MMT advocate to my criticism of MMT on trade deficits. See https://x.com/wgoggin/status/1916273787663696355.

What I do reject is the belief that this ergodic aphorism can be used as a guide to economic development in our non-ergodic world.

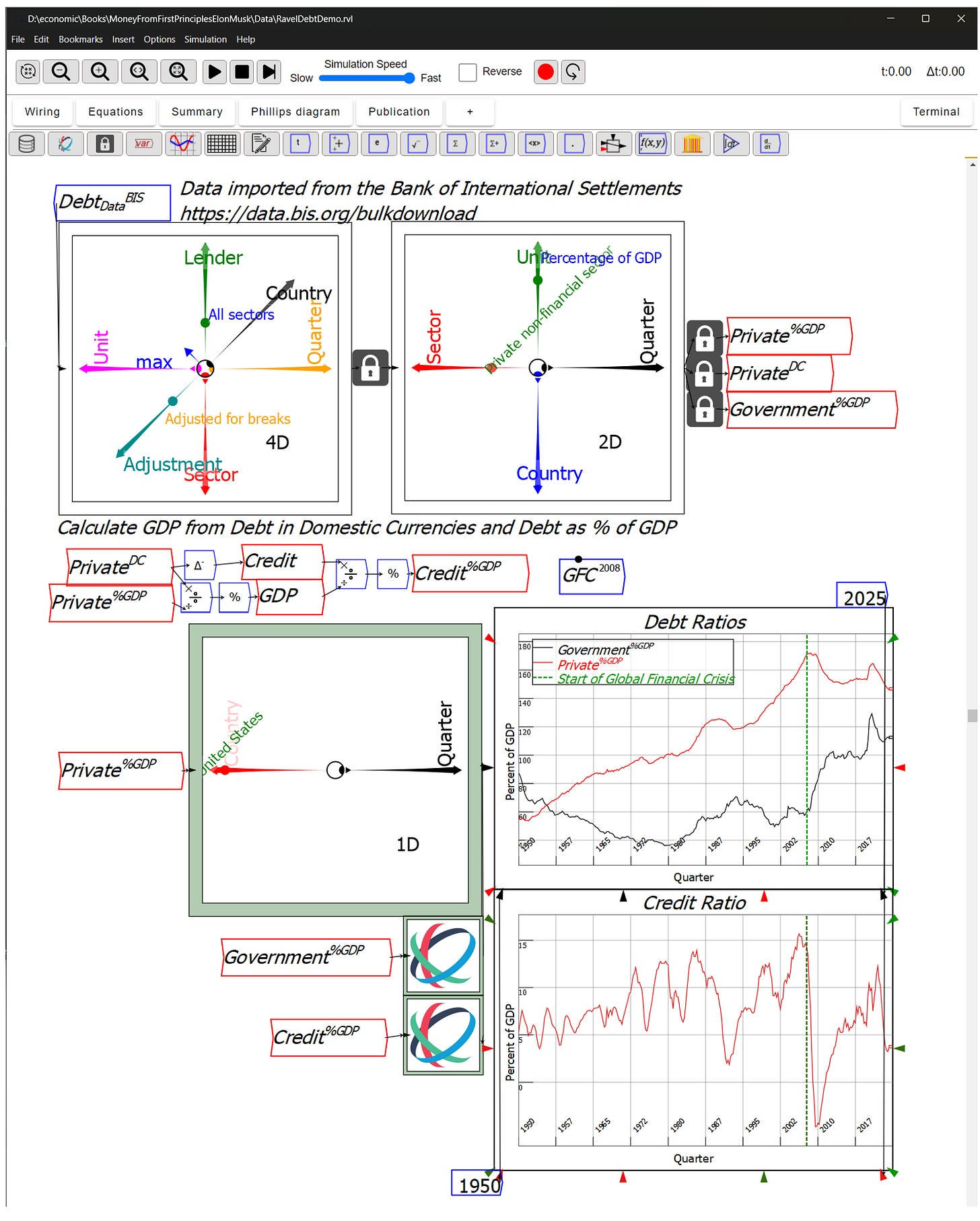

Ravel

All the data analysis and modelling done in this book has used Ravel, a system-dynamics program that I developed jointly with the physicist and high-performance-computing programmer Dr. Russell Standish.[3]If you are an engineer, it has features which should be familiar to you from programs like Matlab’s Simulink—see Figure 68.

Figure 68: The 5-D macroeconomic model developed from first principles in Chapter 7 on Macroeconomics

Its unique capabilities are the ability to model monetary dynamics via its “Godley Tables”, which are unique to Ravel—though they are not patented, and we would be pleased to see other system dynamics programs add this capability—and the unique and patented capacity to manipulate and analyze multidimensional data using the eponymous Ravel.

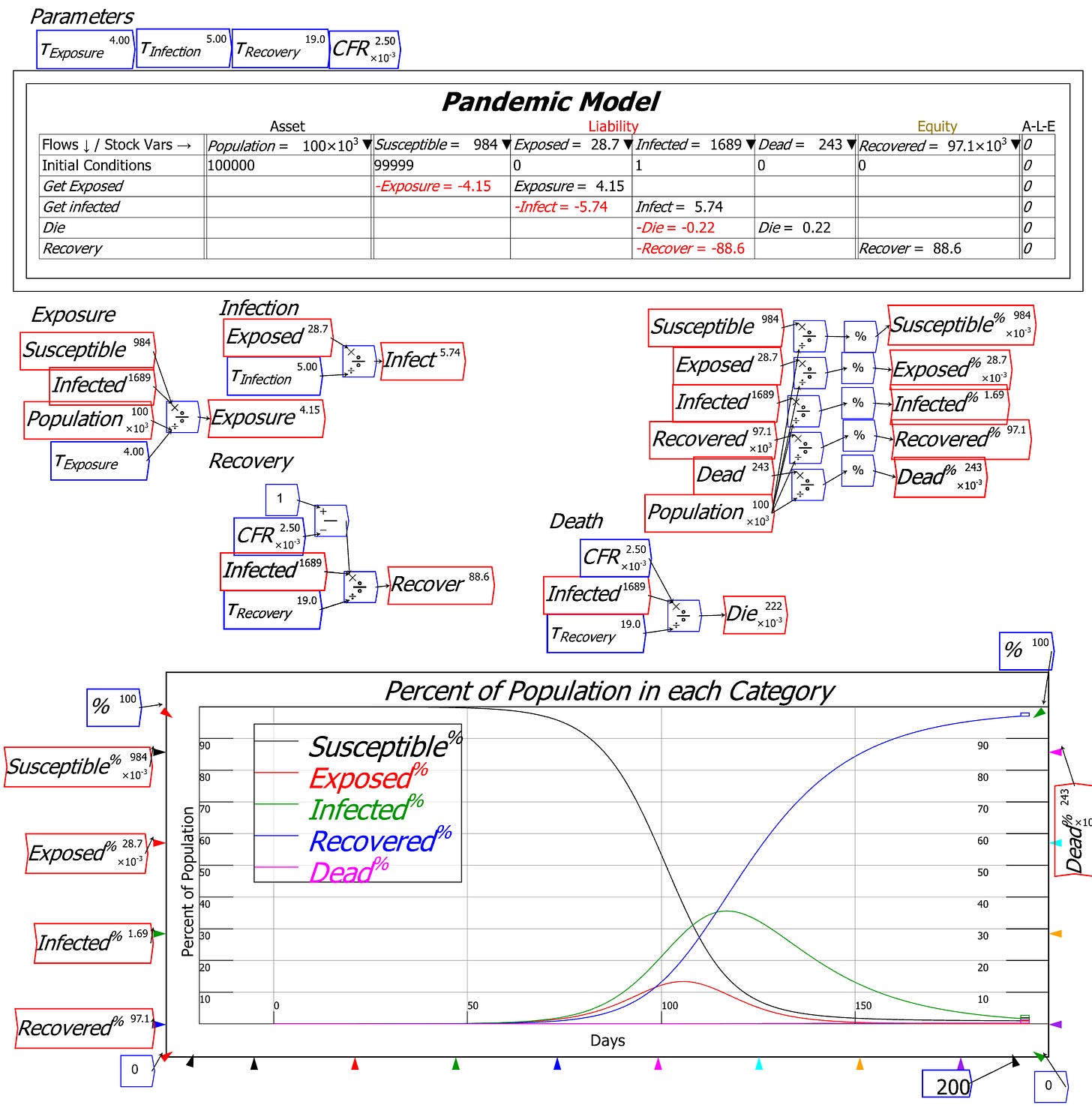

Godley Tables are critical to understanding monetary dynamics—as shown in Chapters 2-4. They can also be used for any process in which conservation applies, whether of mass, energy, or even the number of humans as in SEIRD[4]model of a pandemic—see Figure 69.

Figure 69: A simple model of a pandemic in Ravel

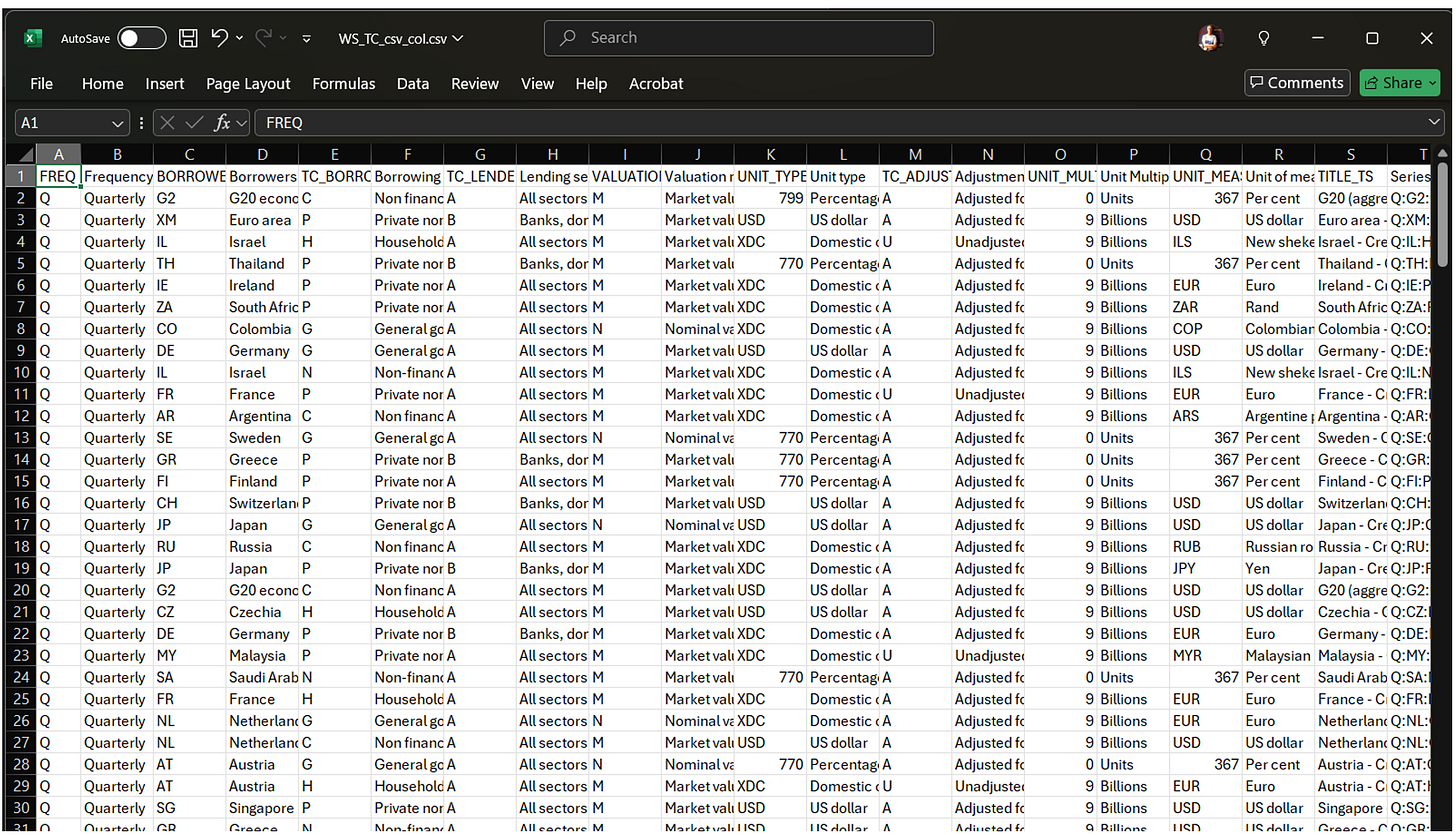

A Ravel—named as such as a play on the word “unravel”—is a graphical way of representing multidimensional data in a way that is far more intuitive than columns of data in a spreadsheet, and far easier to drive than a Pivot Table in a “Business Intelligence” (BI) program.

A spreadsheet is limited to 2 dimensions with its rows and columns (Tabs add a pseudo 3rd dimension, but Tab-based formulas in a spreadsheet are even clunkier than cell reference formulas). Pivot Tables let you extract structured information from a database, but they are hard to manipulate, and can’t easily be combined. Furthermore, the default view in Excel is cell-based. This is bearable for small data files, but when a large data file is loaded—like the Bank of International Settlements database on private and government debt for about 40 countries over the last 80 years—you “can’t see the forest for the trees”: see Figure 70.

Figure 70: The raw CSV file used for the analysis shown in Figure 71

Ravel imports that barely structured data into a structured multidimensional object we also call a Ravel, which works like an airplane’s “6-degrees-of-freedom” compass (only it’s not limited to just six dimensions). It’s easy to select subsets of data from a Ravel, to compress unnecessary dimensions in the data, to rotate data to see information from different angles, and to allocate slices of data to variables on which you can perform mathematical operations.

For example, the BIS database on debt has information on private debt in domestic currencies, the US dollar, and as a percentage of GDP. It’s easy to derive data on credit—the annual change in private debt—but to see credit as a percentage of GDP, you need data on GDP that isn’t stored in this file. There’s an easy formula to derive GDP from that data:

To apply this formula in a spreadsheet would require a nightmare of replicated cell-reference formulas: one for each combination of the 43 countries and about 330 quarters in the database. That same result requires just one set of flowchart equations in Ravel—see Figure 71:

Figure 71: Deriving Credit and Credit as a percentage of GDP in Ravel for 43 countries over 333 quarters

The combination of the Ravel for data manipulation with Ravel’s flowchart formulas gives you an easy way to perform complex analysis while fully documenting your logic—see Figure 72

Figure 72: The data analysis component of Ravel

Ravel is currently marketed via Patreon for $1 per month for the modelling only component, and $7 per month for the data analysis component as well. To acquire a copy of Ravel, subscribe at https://www.patreon.com/Ravelation/. Until early June 2025, you can get a free copy of the system dynamics component of Ravel from https://www.patreon.com/posts/free-download-of-124194565, and you can also try it out the data analysis component on a 7-day free trial (it will continue to work for up to 75 days after your trial expires).

A different approach to economics

I teach the approach to economics that I use in this book in an online lecture class which my marketing partners and I call the “Rebel Economist Challenge”. If you would like to learn this approach, consider enrolling in the course via the link:

https://book.stevekeenfree.com/

Figure 73: Me mid-lecture from my office in Amsterdam

You will join a community of many hundreds of critical thinkers from across the globe, who are fast becoming friends via the conversations that follow every lecture, and by text-chatting on the lecture platform Skool (https://www.skool.com/rebel-economists-mastermind-4713). The classes are given at 1pm New York time on Wednesdays, and 6pm Sydney time on Thursdays. There are over 50 weekly lectures in the course, broken down into 12 subject areas. Most lectures take 30-45 minutes, and are followed by 60-90 minutes of stimulating conversation.

Figure 74: A screenshot of some of the students during a lecture

When you go through the application process via

https://www.stevekeen.com/?spredirect=1

or

https://book.stevekeenfree.com/

(the latter link circumvents some of the marketing) and sign up, you will start somewhere in this cycle and have a year’s worth of lectures ahead of you. The marketing company promotes the program as the “7 Week Rebel Economics Challenge”, since most of their clients do deliver just 7 lectures in their programs. In my case, the 7 weeks refers to the fact that you have that long to decide whether the program is for you: if you decide not after 7 weeks, you can get a no-questions-asked full refund.

As I write these words, we are just completing the first full cycle of lectures—next week’s will be on Ricardo and Comparative Advantage, and a few weeks later, I’ll restart the course with the first lecture on the many flaws in Neoclassical economics, and how I first became aware of them.

[1] See https://ergodicityeconomics.com/2023/07/28/the-infamous-coin-toss/.

[2] See https://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2003/11/10/352872/index.htm.

[3]See https://www.hpcoders.com.au/rks.html.

[4] SEIRD stands for “Susceptible, Exposed, Infected, Recovered, Dead”