Chapter 04: Endogenous Money, of Money and Macroeconomics from First Principles, for Elon Musk and Other Engineers

Advocates of the Endogenous Money model—which I prefer to call Bank-Originated Money and Debt, or BOMD for short—reject the Loanable Funds model as structurally incorrect. Banks are not intermediaries, they assert, but loan originators. This was a minority and non-mainstream position in economics, until it was endorsed by some Central Banks after the Global Financial Crisis {McLeay, 2014 #5066;Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017 #5312}. In a paper entitled “Money creation in the modern economy”, The Bank of England rejected both the Loanable Funds and the Money Multiplier models:

Money creation in practice differs from some popular misconceptions — banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them, and nor do they ‘multiply up’ central bank money to create new loans and deposits…

The reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks: Rather than banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits. {McLeay, 2014 #5066`, p. 14}

The Bundesbank “The role of banks, non- banks and the Central Bank in the money creation process” made similar assertions, based on bank accounting:

It suffices to look at the creation of (book) money as a set of straightforward accounting entries to grasp that money and credit are created as the result of complex interactions between banks, non- banks and the central bank. And a bank’s ability to grant loans and create money has nothing to do with whether it already has excess reserves or deposits at its disposal…

A bank can grant loans without any prior inflows of customer deposits. In fact, book money is created as a result of an accounting entry: when a bank grants a loan, it posts the associated credit entry for the customer as a sight deposit by the latter and therefore as a liability on the liability side of its own balance sheet. This refutes a popular misconception that banks act simply as intermediaries at the time of lending—ie that banks can only grant loans using funds placed with them previously as deposits by other customers {Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017 #5312`, pp. 13`, 17}

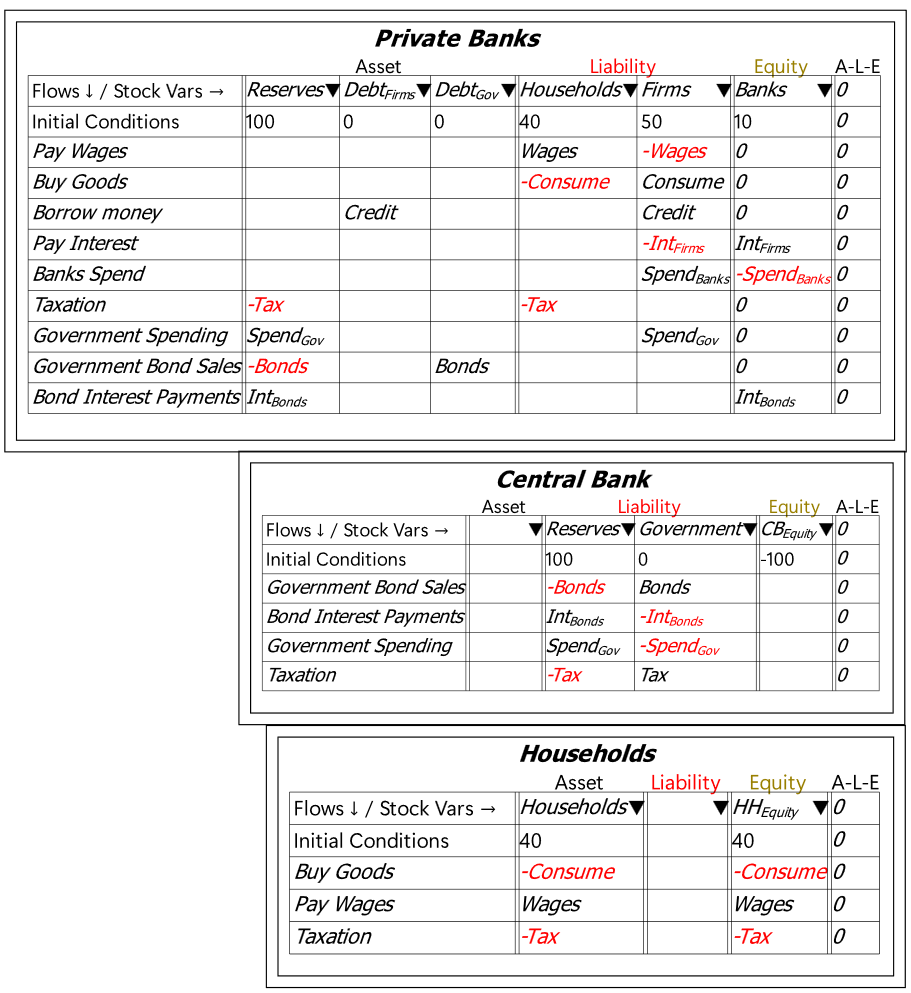

We can check whether this accounting-based perspective makes any difference to the impact of sustained government deficits, by editing the structure of the Loanable Funds model developed in the previous chapter, so that:

Both DebtFirms and DebtGov are Assets of the Private Banks, not Households;

The Government account is a liability of the Central Bank, not the Private Banks;

Interest payments are made to Banks, not Households; and

Deleting Fees. Though Private Banks do charge Fees, these are not its primary income source, nor are they related to the level of corporate debt, as in the Loanable Funds model.

These changes primarily affect the Private Banks, Central Bank and Households Godley Tables—see Figure 14.

Figure 14: The altered Godley Tables for Private Banks, the Central Bank, and Households

Running this model with otherwise the same settings as for Loanable Funds—the same flow definitions and parameter values, including the 1% of GDP deficit—generates the result shown in Figure 14. Both private bank accounts and GDP grow, and the government debt to GDP level stabilises as the money supply and the economy grow. There is no crisis.

Figure 15: Endogenous money with a sustained 1% of GDP Deficit

The differential equations of this model are:

Notable aspects of this model when compared to Loanable Funds are that, whereas there were no operations on the Asset side of the Private Banks Table in Loanable Funds (see Figure 10), there are five operations on the Asset side of the banking sector’s ledger in Endogenous Money:

Credit (which can be positive or negative) increases the level of DebtFirms;

Bonds decrease Reserves and increase DebtGov;

Tax, which reduces Reserves;

SpendGov, which increases Reserves; and

IntBonds, which increases Reserves.

The primary difference between these two models is that all operations in Loanable Funds occur on the Liabilities and Equity side of the banking sector’s ledger. Since all operations must be shown twice, these operations all cancel out.

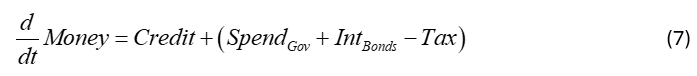

In BOMD, the operations which occur on both the Assets and Liabilities/Equity side of the ledger change the amount of money. Leaving aside Cash, which is a tiny fraction of money today, the sum of Deposit accounts at banks, plus the short-term equity of the banking sector, is the money supply. Therefore, we can define the rate of change of the money supply as:

The first term represents private money creation, the bracketed term represents government money creation. The bracketed term is also identical in magnitude, and opposite in sign, to the change in equity for the Treasury:

The flows in Equation are also identical in magnitude and opposite in sign to the change in equity for the private sector—the sum of the Equity values of Private Banks, Firms and Households in this model. In Equation , the red terms cancel out, leaving only the black terms:

Defining the sum of the changes in the equity of Firms, Households and Banks as PrivateEquity, we have that:

This is the same magnitude, and the opposite sign, as the change in the government’s equity. An increase in the negative equity of the Government sector creates identical positive equity for the non-government sectors.

This indicates that a government deficit is not a bug of the system, but a feature. It is how “fiat” money is created. Private banks create credit-based money by marking up their Assets (loans) and Liabilities (Deposits) simultaneously. The government creates money by going into negative financial equity, which creates an identical magnitude of positive equity for the non-government sector. This is the corollary of the conservation law noted earlier, that the sum of all financial equity is zero.

Further Bond Operations

The model of Endogenous Money developed here is constrained by the Loanable Funds model from which it was derived. We can now extend it to include two more standard features of the current system: bond purchases by the Central Bank, and bonds sales to non-banks by the private banks. This adds three more rows to the Private Banks table, and creates an Asset for the Central Bank—see Figure 16.

Figure 16: Including Private Bank bond sales and Central Bank Open Market Operations

This adds two more means by which fiat money can be created and destroyed. Bond sales by private banks to non-banks are financed by non-banks reducing their deposits, which destroys money; and Central Bank purchases of Bonds from Non-Banks create money.

The sale of bonds by banks to non-banks reverses the money creation effect of a government deficit, while it also adds another method of government money creation—paying interest on bonds owned by the non-bank private sector. Central Bank bond purchases from non-banks also create money. The general formula for money creation is shown in Equation 11:

Finally, the capacity of the Central Bank to buy bonds off the private sector is effectively unlimited. Bernanke, despite being an advocate of the “Loanable Funds” model, once said that “the U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press (or, today, its electronic equivalent), that allows it to produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes” {Bernanke, 2002 #2083}. Since the Central Bank can buy bonds by marking up both sides of its balance sheet, it would be feasible for the Central Bank to buy all outstanding government bonds, and thus reduce the interest payments on government debt to zero (since Treasuries either pay no interest on bonds owned by their Central Banks, or the interest payments are remitted back to the Treasury since it is the effective owner of the Central Bank).

There is, therefore, no fiscal crisis of the State from the mere fact that its spending exceeds taxation. There can be other problems, including inflation and trade deficits, which I explore later, but government spending in excess of taxation is a feature, not a bug, of a mixed fiat-credit monetary system.

But the State has helped trigger credit crises in the past, by attempting to eliminate its debt. Arguably, a major factor in such crises—in addition to the destruction of part of the money supply—is that, in the absence of government debt and deficits, the private non-bank sectors of the economy must be in negative financial equity.