Britain Can’t Afford Rachel Reeves (Final)

Reeves's conventional economics predicts disaster from deficits, but her policies will cause disaster in the real world

Rachel Reeves’s determination to cut the government deficit is based on her acceptance of the economic model of money (and the impact of government spending) that she learnt in her PPE and Master’s degrees. As I explained in the first post, this is the model of “Loanable Funds”: there is a market for borrowing in which the government and the private sector compete, and government borrowing “crowds out” private borrowing, leading to a higher interest rate and a lower level of investment. To quote Mankiw again:

Consider first the effects of an increase in government purchases… The immediate impact is to increase the demand for goods and services… the increase in government purchases must be met by an equal decrease in investment. To induce investment to fall, the interest rate must rise. Hence, the increase in government purchases causes the interest rate to increase and investment to decrease. Government purchases are said to crowd out investment. (p. 73. Italics emphasis added)

Figure 1: Textbook graphical representation of Loanable Funds

If this theory accurately described reality, then there would be a serious problem with the government deficit, and Reeves would be correct in trying to reduce it. To see whether it is correct, we have to go beyond simple textbook drawings, to see what the “Loanable Funds” model would look like in the real world—and that means putting it in double-entry bookkeeping form, since banks and the entire financial system run on double-entry bookkeeping.

To cut to the chase for those who don’t want to read a long technical post, the takeaways are that, if Loanable Funds was an accurate model of reality, then:

Running a deficit would indeed cause a crisis in the future, as continual deficits caused rising interest rates, which ultimately bankrupt the Firm sector;

Not running a deficit results in a sustainable economy (but one which does not grow, because there is nothing in the model that alters the quantity of money;

However, Loanable funds is a false model, because banks are not mere “intermediaries” between Households who save and Firms who borrow, but originators of money and debt;

In the real world, bank lending and government deficits both create money, and enable growth; therefore,

Running a deficit in the real-world results in a higher level of growth than not running a deficit.

The punchline then is that, though Reeves thinks she’s saving the economy from a future catastrophe, what she is really doing is reducing—rather than increasing—the economy’s capacity for growth. This is the exact opposite of what she thinks she is doing.

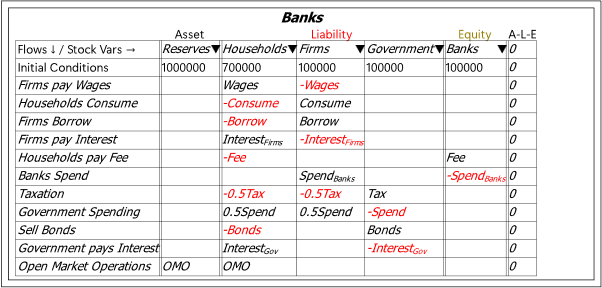

I illustrate this in this post by creating a model of Loanable Funds in which, as in the textbook theory, the supply of money (by Households) and demand for money (by Firms and the Government) depends on the interest rate. In this model, the deposit accounts of Households, Firms, and the Government, are all liabilities of the banking sector—as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Double-entry Bookkeeping representation of Loanable Funds

If the government does not run a deficit, the outcome shown in Figure 3 applies: GDP rises and then stabilises, while interest rates also rise and then stabilise.

Figure 3: Loanable Funds with no Deficit

However, if the government does run a deficit (equal to 1% of GDP in these simulations), then the situation shown in Figure 4 applies: GDP ultimately plunges as rising interest rates make it impossible for firms to service their debts.

Figure 4: Loanable Funds and a Crisis caused by Deficits

This is the catastrophe that Reeves is trying to avert.

But will it actually happen?

Both these outcomes result from the Loanable Funds assumption that Firms and the Government borrow from Households in order to invest and spend. This makes both private (Firm) debt and Government debt assets of the Household sector:

Figure 5: Firm and Government Debt are Household Assets under Loanable Funds

But in the real world, the debts of Firms and the Government are assets of the Banking Sector. Figure 6 shows this real-world situation.

Figure 6: Double-entry Bookkeeping for Bank Originated Money and Debt

These structural changes to the model are the only changes made: all the other equations of the model, including the (false) assumption that Household Deposits determine interest rates, are unchanged.

The outcome is dramatically different, because in the real world, both bank lending and government deficits create money. The mechanisms are different—banks create credit money by expanding their assets (Loans) and liabilities (Deposits) simultaneously; governments create fiat money by going into negative financial equity, which creates an identical magnitude of positive financial equity for the non-government sectors. But these fundamental aspects of the real-world financial system are ignored by Neoclassical economists, because acknowledging them would force them to abandon their equilibrium and barter-based paradigm.

This is why economics textbooks—and Neoclassical economics itself—are so dangerous. Virtually every belief taught in them is wrong.

In the realm of money, there is no market for Loanable Funds. Governments do not borrow from the non-bank public, nor do they really borrow from banks, but rather they sell banks an income-earning, tradeable asset (Bonds), which banks buy using a (historically) non-income-earning, non-tradeable asset (Reserves) that the deficit itself creates.

The consequence of innocent students—and that is what Rachel Reeves really is—believing this false model is catastrophic for the real world, and especially for the poor. The rich can afford private hospitals; the poor rely on public health. The rich can afford to heat their houses; the poor rely on government assistance.

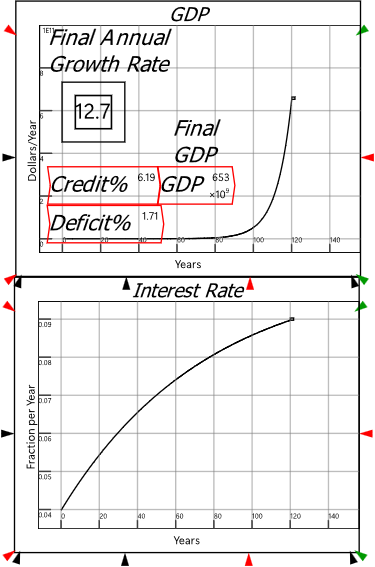

Ironically the rich suffer as well, since, as Kalecki pointed out decades ago, government deficits boost profits. The difference is huge over time. The simulation shown in Figure 7, with a relatively trivial budget deficit of 1% of GDP per year—augmented by the impact of interest payments on government bonds, which boosts the economy as well—the rate of economic growth reaches 12.7% p.a. after 120 years (this is too high, but is an artefact of the interest-rate-determined borrowing levels still assumed in the model; the real-world levels are lower).

Figure 7: GDP and Interest rates with a deficit

On the other hand, if the government runs a balanced budget, the outcome is a substantially lower economic growth rate of 9.5% p.a. As Figure 8 shows, the terminal value of GDP is an order of magnitude lower than with a deficit.

Figure 8: GDP and interest rates without a deficit

These are the dangers of letting the economy be managed by a group of people who sincerely believe a pile of myths. The economic paradigm taught in schools and universities—Neoclassical economics—is an intricate set of persuasive but fundamentally false ideas. There are other such edifices in human society, but none other is given the status of a science in the way economics is, by being taught at Universities, and by being put on a similar pedestal to the hard sciences, and used as the basis for most policy advice to government.

It is unreformable as well. As in any set of mythical beliefs, no element of reality that contradicts the theory can be admitted without the whole edifice collapsing. With apologies to those who believe in the Christian religion, accepting, for example, that firms experience constant or falling marginal costs, would be akin to Christians accepting that Jesus’s wasn’t born to a virgin. That banks create money when they lend, let alone that this has real rather than merely nominal effects, is destructive of the entire paradigm.

Therefore, textbooks continue teaching Loanable Funds, the Money Multiplier, and Fractional Reserve banking, long after some central banks—including the Bank of England and the Bundesbank—said these were myths.

Technical Details

This is a very simple model, created just to illustrate why Loanable Funds—if it accurately described how banks operated—shows that government deficits are a problem. But it doesn’t.

The first bit of turning the accounting into a model is a “Friedmanite” relationship between the amount of money and GDP—though Marx used the same device, so it’s not entirely reactionary: it’s just a simplification to cope with only having one account for firms, which therefore ignores inter-firm commerce, which is a large fraction of GDP. So the turnover rate means that $100 of money generates $200 of GDP per year.

Households and banks are then assumed to spend based on their bank balances, with Households turning over their bank balances several times a year and banks doing so much more slowly.

Figure 9: GDP and consumption

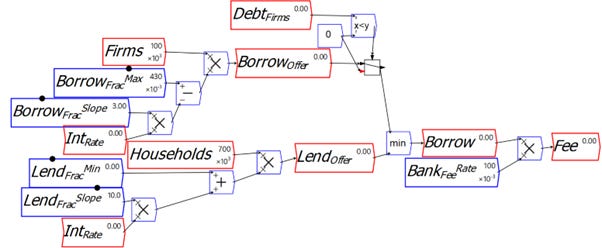

The next section is the most complicated part of the model. It has firms with a negatively sloped desire to borrow, depending on both their current bank balances and the interest rate. Household have a positively sloped desire to lend, based on their current bank balances and the interest rate. The short end of the two determines the actual amount borrowed. The bank’s income then comes from charging an introduction fee to the Households for arranging the loan,

Figure 10: The market for Loanable Funds

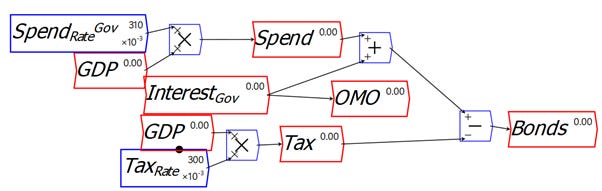

Government spending and taxation are fractions of GDP, both under government control. The government has to pay interest on outstanding bonds owned by the non-government sector (in this model that is only the banking sector since I’ve omitted bank bond sales to non-banks). The Central Bank then undertakes Open Market Operations. These are only considered in the real-world model of bank and government money creation, since if they were included in the fantasy of Loanable Funds, these operations would create money (because there would be an entry on banks’ Liability side in terms of interest on bonds, and one on the Asset side in terms of an increase in Reserves).

Figure 11: Government spending, taxation, and interest payments

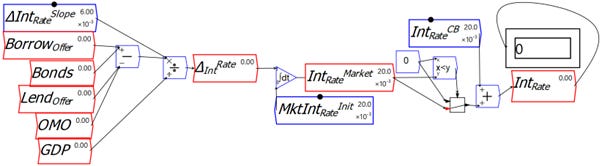

Finally, the interest rate is caused by the demand and supply imbalance. Offers to borrow from Firms, and Bond sales by the government, add to demand. Lending is the supply side. When Open Market Operations are undertaken, this reduces the supply. This determines the rate of change of the interest rate, which is integrated to derive the actual interest rate.

Figure 12: Interest rate determination

The whole model is available from the Patreon post (Substack currently only allows a range of popular file types to be attached to a post.

Figure 13: Full Loanable Funds model with the crisis Reevse expects

Figure 14: Real-world Bank Originated Money and Deb model with the same settings as in Figure 13

References

Kumhof, Michael, and Zoltan Jakab. 2015. "Banks are not intermediaries of loanable funds — and why this matters." In Working Paper. London: Bank of England.

Mankiw, N. Gregory. 2016. Principles of Macroeconomics, 9th edition (Macmillan: New York).

McLeay, Michael, Amar Radia, and Ryland Thomas. 2014. 'Money creation in the modern economy', Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, 2014 Q1: 14-27.

For future reference, I made, a while back, a handy-dandy list of major international banks/institutions who've come out, as it were, against the false paradigm and explained how banking really works https://www.economania.co.uk/various-authors/where-money-comes-from.htm

Theory without pungent application is a eunuck, and cynicism is the intellectual disease of self stopping.

All new paradigm concepts are apparently absurd because they are always in complete conceptual opposition to present orthodoxy...until they are the solution to systemic anomalies.

Mass movements advocating "an idea whose time has come" always precede political change. Accounting is the temporal universe score card of money and probably the most temporal universe reality anchoring discipline humanity has ever invented. Thus:

Retail sale being the single aggregative/macro-economic as in universally participated in point of the entire economic process is the best place to implement a gifting monetary policy utilizing equal debits and credits that sum to zero.

The point of borrowing/loan signing is probably the second most participated in point in the entire economic process and hence the best place and time to integrate debt jubilee continuously into that process.

Proverbs are wisdom because they are the integration of insight and action.